Amber Rudd: Boris’s split personality is revealed in his memoir – he’s more Beano than Gladstone

In cabinet, the former minister wanted to hold a mirror up to Boris Johnson and regularly saw his mask slip. As his new memoir is published full of wild untruths and shameless exaggeration, she writes, readers will be left wondering if a real Boris exists at all

Having once said that Boris was the life and soul of the party, but not safe in taxis, I have to say that having read his memoir he is not safe behind a keyboard either. That is, if you are looking for truth, integrity, seriousness and profundity in a politician, let alone a prime minister.

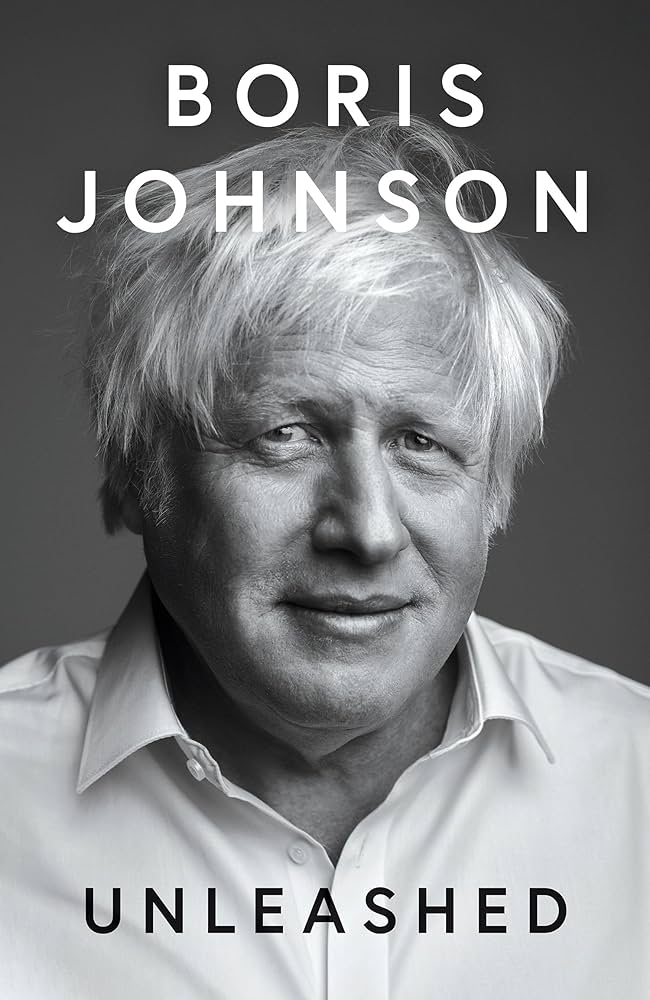

His new memoir, Unleashed, is Billy Bunter let loose in Westminster with its endless whooses and biffs and sockeroos. Is Boris a serious writer, a chronicler of the Covid years, an eye-witness to some of the most challenging and troubled times in our island’s history? No, he’s more Beano or Dandy than Gladstone or even Rory Stewart. Farcical rather than factual seems to be his preferred mode of travel. This is a book of two voices – the caricature bombastic Boris, and the calm, quiet and calculating Boris. Some would say this perfectly reflects the two-faced nature of Boris Johnson the Janus – a classical allusion he will understand better than most, even if he doesn’t appreciate it.

But then Boris was always a split personality. He did after all write two essays, one that argued for Britain leaving the EU and the other with us remaining. He was split, pulled in opposite directions, but not for the reasons you might expect. He was agonising over what would best serve him. And was always thus.

Sitting opposite Boris in cabinet, I wanted to hold a mirror up to him. Did he realise the appalling faces he pulled when Theresa May, the then prime minister, was speaking? That face he adopts of amused determination – shoulders hunched, brow scowled, mouth pursed as though bracing for an assault or a charge? Nobody maintains that pose for long and when he forgot to hold it his look would settle into the innocent picture covering the front of Unleashed... But it was never long before the classic Boris face returned.

The first version is that caricature of himself, the exaggerated performance that makes him almost un-satirisable. You’ll remember it from speeches filled with explosive language and absurdist imagery – it’s what makes him such a memorable orator and, for a while, such an unstoppable force. The second voice is a much more calm, emotionally involved tone, whose gentle concern almost makes you believe his desire to do good. Almost being the key word here.

What’s most interesting is when he chooses to use both versions throughout the book and at the end, you’re left wondering which is the real one, and which is the performance. Fame or infamy? Family man or unfaithful rogue? Courageous or calamitous? Always we are left wondering who is the real Boris. And if a real Boris exists at all. We discover a man whose mission never gets quite beyond “boostering” – not the economy, for which the term was coined, but boostering Boris himself.

Unsurprisingly the first, almost parody, voice of Boris is most clear in his chapters on Brexit. Boris casts himself undoubtedly and inevitably as the hero of Brexit – he revels in his own dazzling genius, in the campaign’s simplicity, in its crude but effective language, and his own “brilliant clarity of message”. And he ridicules the Remain campaign, which “had everything except the one thing you really need: they lacked conviction”. What on earth does he think the rest of us were doing? Campaigning so hard it put political careers, let alone friendships, on the line. If he thinks we lacked conviction, I’ve got a bus with a slogan to sell him. And it would have a slogan which was not ridiculed for being full of fantasy facts.

While this exuberant, provocative Boris recalls these years, as if they were a personal military triumph for his country, that jubilant joy at winning grinds to a shocking, screeching halt as the victory sinks in. Let me put it plainly: in a memoir designed to cement his legacy, it screams out that he had no plan apart from to get a medal for winning. The horror of his justification for having no clue how to proceed once he’d convinced the country to follow him out of Europe may test the patience of readers who were not Brexit supporters. “Now what the hell were we supposed to do,” he whines. “We had no plan for government ... negotiation ... it is utterly infuriating that we should be blamed.”

If politics were a jolly game with no consequences, his account would be entertaining. But as I’m someone who spent so long screaming “they’ve got no plan for when they win”, it’s shocking to see it spelt out so clearly and shamelessly. Sangfroid is served up even colder than what David Cameron felt towards Boris when he was betrayed over Brexit. We learn that he was led to believe Boris would support him and then made mafia-like threats when Boris did his inevitable betrayal.

The second voice of Boris, and unsurprisingly the version I prefer, appears in chapters such as Boris the London mayor. Here his tone is full of quiet determination for causes like reducing knife crime and improving transport. His description of lying awake at night, messaging with his deputy mayor Kit Malthouse and putting in place measures to bring the murders in the capital down, are moving. And his love for London comes through powerfully.

The chapter on the 2012 Olympics coming together despite mishaps is fun. Followed in quick succession by the London riots and the effective policing to stop them. He refers to his purchase of water cannons from Germany which were blocked from use by Theresa May, who he refers to as “still doing her liberal thing” – an unusual description for that particular former home secretary.

But no matter which side of Boris he’s pushing, it’s clear that he always views himself as the lead character and driving force behind everything (everything successful at least), so much so that throughout this book he gives very little acknowledgement of other senior politicians around him. The exception is Theresa May, who he casually and constantly disparages. His physical descriptions of her nostrils have the whiff of misogyny – again a reverse side to the man who sees himself as something of a success with women.

In his description of the government’s handling of the Skripal poisoning in March 2018, according to his book, the controlled and purposeful response was all Boris’s doing. Not true. As someone who chaired the Cobra meetings over that period, I can clarify that it was in fact Theresa May’s leadership and steely determination that was the real guiding strength during this time. And when it comes to getting the Americans to agree to expel 60 Russian officials in solidarity, while you wouldn’t know it from Boris, the credit should really go to our ambassador at the time, Sir Kim Darroch.

Darroch’s career is one of a long list of people whose careers ended after getting close to Boris. Dominic Cummings (described as a “homicidal robot” in the book by a Boris who regrets not firing him). Lee Cain, his press spokesperson. Even Owen Paterson, inadvertently, and Richard Sharp. Many loved his bonhomie, but they all forget what Sigmund Freud said: there is no such thing as a joke. Boris has always been the joker but, as he likes comic effects, he may remember that in Batman the joker was the assassin.

As a professed One Nation Tory, Boris turned Britain into two nations at war with Remain and Leave tribes, a civil war only this time without muskets. He also blew up the Tory party, twice. Once with the Brexit saga and secondly under his premiership in which he was threatened with a vote of no confidence to make him leave No 10.

There are also some notable absences from this 700-page book. Not least Cummings, who does not appear until page 227. The public were all painfully aware of Boris’s reliance on his fixer and the reach of his power, and yet here he is barely more than a footnote for his boss. It was Cummings who gave the PM the confidence and the strategy to “get Brexit done”, to expel MPs who opposed him, to make commitments he couldn’t keep, and to call a general election in 2019.

In my brief period as secretary of state for work and pensions, I attended regular Cobra meetings for no-deal preparation and witnessed first hand Cummings’s key role; the way he highlighted his power by arriving when he liked, and was deferred to by the chair. But rather than berate him and devote precious pages to him, it makes sense that for Boris, a figure who so loves attention, the greater insult is to give him as little airtime, as is possible. He simply remarks that when Cummings left it was like “a great weight had been lifted”.

Ultimately, while this book appears to champion one cause after another, the only cause that really matters is brand Boris. He is a master of explaining his truth but seems little interested in the actual truth. Boris is a great performer, even on paper, which makes much of it entertaining. (My favourite part is when what he calls his “cockroach invincibility” is finally crushed.) Many people, myself included, have called him a liar, but now I’m left wondering if, when he takes credit for others’ successes or grossly simplifies his own, it’s outright dishonesty or if he is simply delusional and genuinely remembers it that way.

I still don’t know which side of Boris is the real him. The Boris who had a serious brush with death during Covid, or the Boris who considered invading Holland to steal back our vaccines? I’m inclined to believe there is no real Boris – that he has merely become a performance of himself, fully believing he’s the main character and hero in every tale.

Even when you spoke to Boris in person, you never knew who you’d be addressing but when he gets home and takes off the mask, which version remains? The caricatured orator or the caring statesman. Does he even know? Or is he, like Janus, actually both versions equally, and happy to choose the mask that suits that day’s audience best?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks