Cheaper pints of beer could be coming thanks to new scientific discovery

The discovery is based on a new “bottom-up” tapping system in which a nozzle pushes up a magnet

Cheaper pub pints could be on the horizon after scientists worked out how to extinguish too much FROTH.

The head is generated in the first moments of pouring - with higher temperatures and pressures producing most.

It sheds fresh light on why most drinkers prefer a cool lager to a warm real ale.

The discovery is based on a new “bottom-up” tapping system in which a nozzle pushes up a magnet.

It will be music to boozers’ ears. The cost of living crisis means an average pint costs over £5.50 - with the most expensive more than £8.

The price could soar to £9 in some areas this summer, say industry insiders.

Lead author Dr Wenjing Lyu, of the American Institute of Physics, said: “This will help in controlling foam formation, reducing consumption and pouring time and improving the overall efficiency of the process.”

Foam is big business - boosting the distinctive look of brews from Guinness to Best Bitter. It also adds to aromas so appreciated by connoisseurs.

But people tend to feel short-changed when served a pint with too much froth.

Some are tempted to send it right back - and demand another.

The complex links between beer components, the vessel from which it’s poured and the glass it goes into has mystified experts for decades.

The new study provides the most accurate predictions to date of how the white froth will form.

When the magnet at the bottom rises it creates a temporary inlet - moving back into place as the glass fills and the beverage is ready to drink.

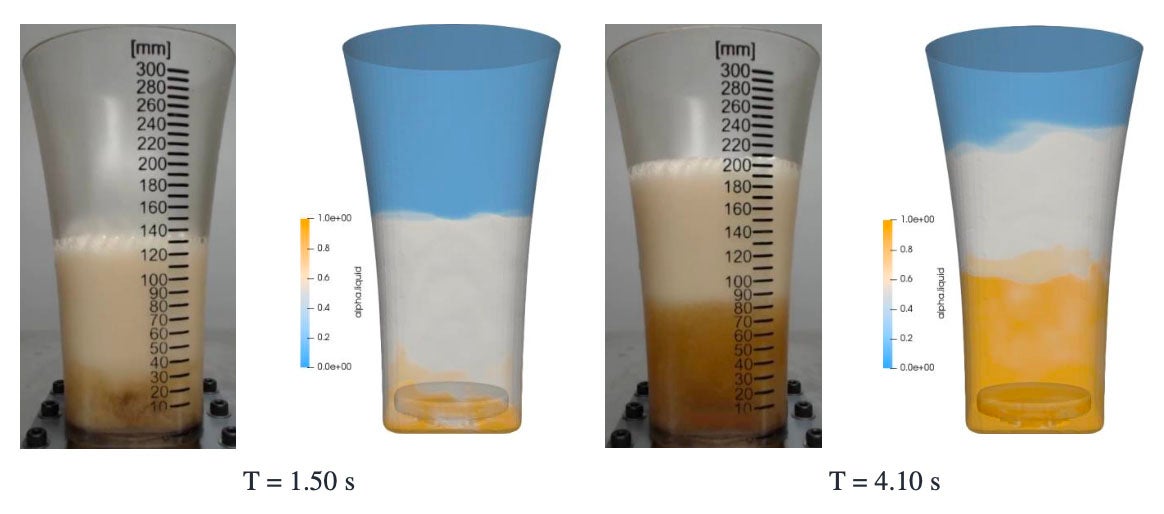

After a series of tests to establish stable pouring conditions the US team developed a computer model which was validated with experiments.

They showed the beer’s liquid phase kicked in after production of the head - not before.

This was mainly determined by bubble size. It caused the foam to slowly decay - taking about 25 times longer to fully fizzle out than to form.

Dr Lyu added: “By accurately simulating the foaming process, our model can help to improve the quality of the final product, reduce costs, and increase productivity in industries such as food and beverage, chemical and others.”

The study was published in the journal Physics of Fluids.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments