Children among ‘staggeringly high’ number of autistic people being drawn into terrorism, watchdog warns

‘It is as if a social problem has been unearthed and fallen into lap of counter-terrorism professionals’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A “staggeringly high” number of autistic people - including children - are being drawn into terrorism, it has been warned.

In a speech marking the 16th anniversary of the 7/7 London bombings, the Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation is to say it is “necessary to speak about autism”.

It comes after police revealed that more than one in 10 terror suspects arrested in Britain is now a child, and that most are linked to right-wing extremism.

Jonathan Hall QC will say autism is a “relevant factor” for people being drawn into terrorist violence, alongside other cognitive difficulties and a person’s family background.

He will tell an event hosted by think-tank Bright Blue on Wednesday: “My understanding is that the incidence of autism in Prevent referrals is also staggeringly high.

“It is as if a social problem has been unearthed and fallen into lap of counter-terrorism professionals.”

Mr Hall will question whether criminal prosecution is the right outcome in all cases, such as those over the possession of “material likely to be useful to a terrorist”.

”Is the use of strong powers to detect and investigate suspected terrorism in children justified?” he will ask.

“I believe it is because of the potential risk to the general public, but is the criminal justice outcome the right one in all cases?”

Mr Hall will say that possessing terrorist material “does not necessarily mean you are going to do something with it”.

“What about autistic people who simply develop what is called a ‘special interest’ in this sort of material? Police and prosecutors fret about whether there is an alternative to arrest and prosecution.”

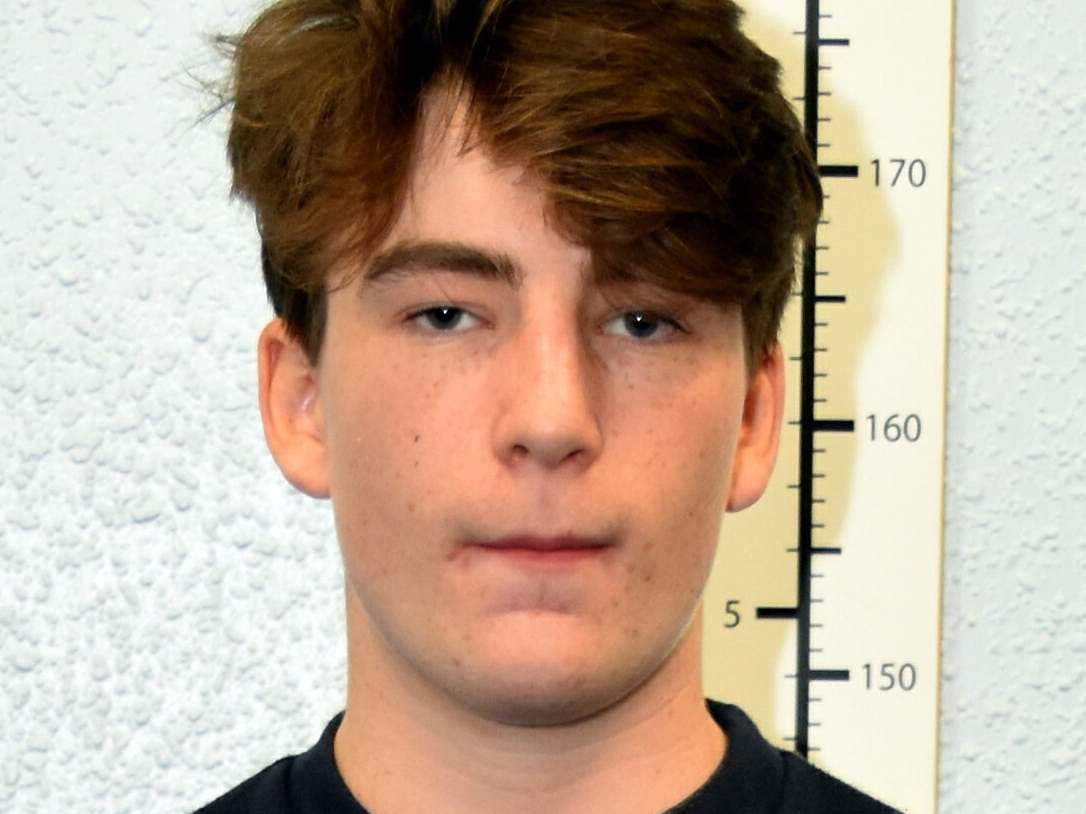

Mr Hall is to draw attention to several autistic teenagers who have been convicted of plotting terror attacks in recent cases, including Isis supporter Lloyd Gunton and neo-Nazi Jack Reed.

A judge found that Reed, who is one of the UK’s youngest terror plotters, had autism spectrum disorder that played a part in offending and online behaviour dating back to the age of 13.

Ben Hannam, the former Metropolitan Police officer who was convicted of National Action membership earlier this year, was on the autism spectrum and socially isolated when he joined the terrorist group as a teenager.

The role of autism in terror offending was considered by the Court of Appeal in January, when neo-Nazi Paul Dunleavy, then 17, appealed his conviction.

He was jailed for five-and-a-half years for preparing acts of terrorism by researching how to convert a blank-firing gun into a live weapon, and providing “advice and encouragement” to others online.

The Court of Appeal heard evidence that “many autistic people have intense and highly focused interests”, such as Dunleavy’s obsession with guns, but judges ruled that autism spectrum disorder did not “make it reasonable for him to possess [terrorist] information for a particular purpose when it would not be reasonable for anyone else to do so”.

Lawyers defending autistic people accused of terror offences frequently argue that associated traits and characteristics played an instrumental part in their actions.

In November, a barrister representing teenage neo-Nazi propagandist Harry Vaughan said his autism and a “deficiency in emotional intelligence” made him susceptible to influence from online groups.

All cases have primarily involved online radicalisation, either where the defendants have “self-initiated”, or come into contact with other extremists through social media, gaming and chat forums.

Mr Hall’s most recent report on the operation of terror laws in Britain said that evidence suggested Autism Spectrum Disorder was “over-represented in lone-actor terrorist samples, compared to the general population”.

“Unpalatable though it may be, a large number of lone actor plots are believed by counter-terror police, rightly or wrongly, to involve individuals on the autistic spectrum,” it added.

“Individuals suffering from poor mental health or learning difficulties are often extremely isolated and may be particularly susceptible to online radicalisation.”

The national coordinator for the Prevent counter-extremism programme, chief superintendent Nik Adams, previously told The Independent that autistic people were “more vulnerable to be given that obsession, fascination, fixation”.

He warned that online terrorist propaganda “plays entirely to that because what it seeks to do is mobilise people very quickly to do something really terrible”.

Ch Supt Adams said the number of people being referred to Prevent with mixed or unclear ideological beliefs was also rising and included those with “complex needs” including autism and mental illness.

Clare Hughes, criminal justice manager at the National Autistic Society, said many autistic people and families were concerned that high-profile cases could “warp public understanding”.

“The vast majority of the 700,000 autistic people in the UK are law abiding – sometimes particularly so because of a propensity to know and stick to the rules,” she added.

“If autistic people do come into contact with the criminal justice system, it’s absolutely essential that professionals working in the system really understand autism and that specialist support is available for autistic children and adults when it’s needed.

“At the same time, the right early support must be available to stop people getting into dangerous situations, including mental health support to help autistic people to navigate what can feel like a chaotic and overwhelming world.”