What the battle for abortion rights tells us about the row over assisted dying

As Kim Leadbeater prepares for her assisted dying bill to be read in parliament, Sean O’Grady looks at the lessons that can be learnt from the fight to legalise terminations more than 50 years ago

A new-ish backbencher, against the odds, takes on much of the political and medical establishment to pioneer a momentous, but highly controversial, private member’s bill. Many previous attempts have failed. Doctors, faith organisations, parliamentarians and of course the public are all concerned; many are passionate about the moral principles and the procedural details. The issue is fairly, if broadly, described as one of “life and death”. Bodily autonomy is at the centre of the debate.

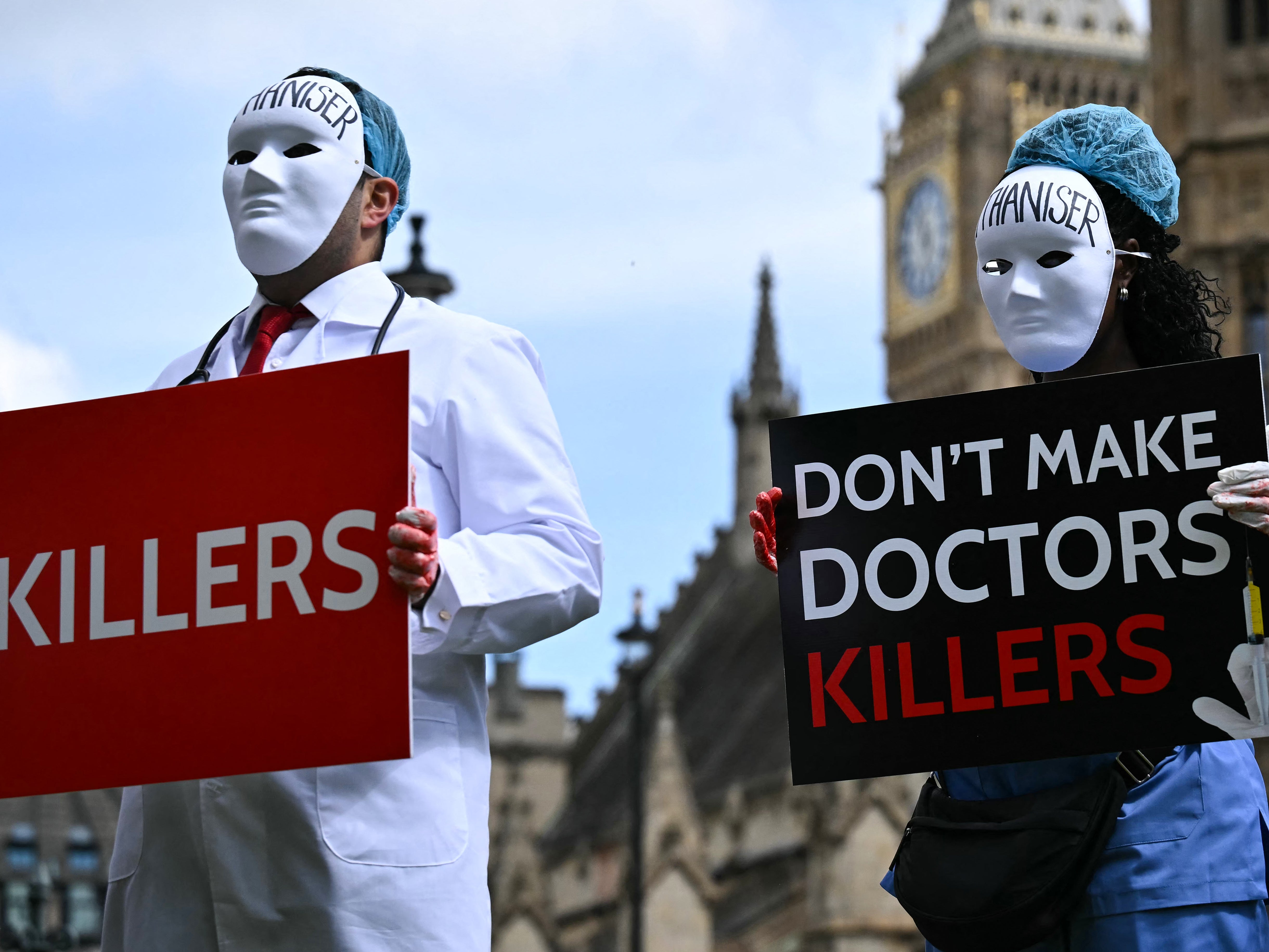

This is the background to Kim Leadbeater’s assisted dying proposal, formally known as the Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill, which was introduced to parliament on 16 October and will be properly debated at the second reading, on Friday 29 November.

Leadbeater came top in the traditional ballot (ie raffle) for a chance to make history and chose this cause to be hers. An MP since she won a hard-fought by-election in Batley in 2021, if she succeeds then “her” law will change the lives of many thousands of families in the decades ahead. One piece of encouragement for her is that something of the same has been done before…

The Abortion Act 1967 was not only placed on the statute book by a backbencher but still remains the basic law governing the procedure to this day.

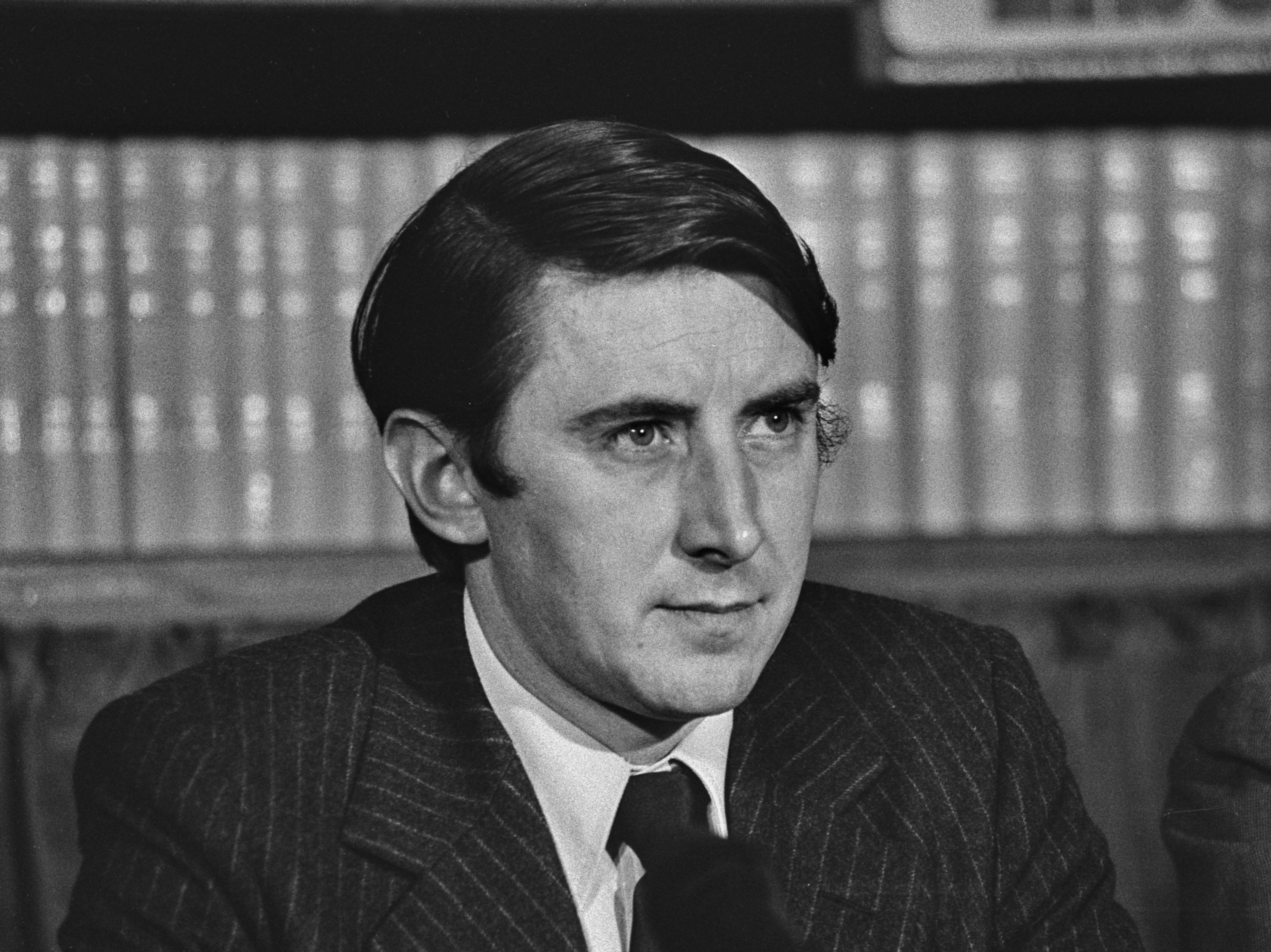

It was the abiding achievement of a young (27) Liberal MP by the name of David Steel, now Lord Steel of Aikwood, who’d won a by-election of his own in 1965. By good fortune, in a Commons Committee room in the spring of 1966, his name popped out third in this curious custom.

After the usual lobbying, and carefully judging the chances of making the most impact tempered by a realistic assessment of success, he decided to end the scandal of so many young women at the time, particularly poorer ones, who were forced to end unwanted pregnancies by resorting to notorious back-street abortionists.

As with assisted dying now, the law was archaic − dating back to the Offences Against the Person Act 1861, and, for assisted dying, to the Suicide Act 1961. For a woman caught trying to get an abortion, the maximum penalty was penal servitude for life or imprisonment for two years with hard labour and solitary confinement. By the 1960s, that was more abhorrent than the crime.

At that time girls from wealthier families who found themselves “in trouble” would have had a relatively straightforward time of enlisting the help of private doctors and lawyers to navigate the law, but they were a minority. For the majority, there could be much misery, and worse if an amateur termination went wrong. It was, in short, a social evil, and being recognised as such.

It is not quite the same with assisted dying or suicide, but the emotional issues do possess the same kind of power, and the questions are similarly distressing, deeply personal and socially divisive. Some people know how to use, say, the Dignitas facility in Switzerland, and have the funds to do so.

Others, not so much. There are also the same concerns about the sanctity of life, and the same weighing of the interests of all involved. Both now and then, people have looked to parliament to take the lead.

In the 15 years before the Steel bill there’d been more than a dozen attempts to sort out the law on abortion, and all had stumbled. A similar number of attempts have been made in recent decades to reform the assisted dying act, and all those have faltered also.

Interestingly, Steel based his bill on a recently discarded text that had passed, but only in the Lords; now Leadbeater’s bill draws a good deal on Lord Falconer’s 2014 legislation, which was ultimately withdrawn. He’s backing Leadbeater’s attempt as well − and a bill from the Commons has more chance of gaining “legitimacy”.

Another striking similarity between the abortion and assisted dying debates is the way the arguments, for many people, were and are so finely balanced. In those days, as Steel so eloquently put it in launching his campaign: “The difficulty in drafting a bill of this kind is to decide how and where to draw the line. We want to stamp out the back-street abortions, but it is not the intention of the promoters of this bill to leave a wide-open door for abortion on demand.”

It is, fair to say, much the same wariness about making assisted dying too easy that makes some so hesitant about committing themselves. A Liberal MP was perhaps ideally placed to plot a middle way.

Back in 1966 and 1967, Steel, as a Liberal, was in an extremely isolated position. The entire elected party numbered just 12, in a Commons where prime minister Harold Wilson’s Labour Party enjoyed a landslide majority of almost 100 seats. Leadbeater at least comes from the governing party, with many colleagues sympathetic to her bill. But she still faces the same challenge that faced Steel before, which is to gain what might be called the indulgence of the government to allow the bill sufficient time and a chance to succeed. Oddly, as things stand, it’s the Liberal Steel who won more allies at the top than Leadbeater did at the time.

Personalities, dynamics and some luck went the right way for Steel. His most powerful ally was Roy Jenkins, the then home secretary. Nearly two decades later, they’d be joint leaders of the SDP/Liberal Alliance, but even at that stage, Jenkins was widely thought of as a “classic liberal”, if not Liberal.

An admirer of HH Asquith, Jenkins had little time for “doctrinaire” socialism and wanted to leave a legacy of social reform − “the civilised society”. His preferred method was to use private members bills from backbench MPs to reform social “moral” legislation that normally demanded free or “conscience” votes, rather than being laughed through as government bills − which would anyway split the ever-fissiparous Labour Party.

That was how Jenkins presided over and facilitated parallel reforms in divorce law, homosexuality and the death penalty − moves that helped define the Sixties. Jenkins initially suggested homosexual law reform as a suitable case to Steel, but the Liberal was warned off by party managers in his own constituency.

In Jenkins’ own words: “While members of the cabinet would be free to vote against them, I would be free to speak (and vote, of course) in their favour from the despatch box and with all the briefing and such authority as I could command as home secretary.”

Would that Leadbeater have that kind of backing now… “neutrality” is not the same as indifference, which the current front bench displays, lacking any great instinct for social reform.

Jenkins, then, was key. But so were others. Unlike Wes Streeting now, Kenneth Robinson, Wilson’s health minister, was with him, while the most senior people in the administration, Wilson, James Callaghan and George Brown were content to let a Liberal take the heat from the critics.

The party leadership was understandably concerned about the impact on the Roman Catholic vote in Labour’s marginal seats in London and Lancashire, for example − just as it might be now about how Muslim voters would react.

Labour’s then chief whip, John Silkin, was the son of Lewis Silkin, the last person to try and make abortion legal. Most valuable of all, Steel was given all the “government” time he required by the leader of the House of Commons, Richard Crossman, who, like Jenkins, considered the project admirably progressive. It was a bit of an ordeal for Steel, however, as he tells it:

“I went to see Dick Crossman in his room, full of awe as a junior member. He gave me a whisky. I rehearsed the arguments for granting time − weight of opinion in the House, long overdue reform, campaign outside etc, etc. He absentmindedly poured a second helping − of brandy − into my whisky glass. This was no time to complain. In the cause of getting my bill, I drank the revolting mixture. We got two extra night sittings, and on the morning of 14 July, I rose to move the third reading, which was approved by 167 to 83. The bill went through another tortuous process in the Lords before receiving the royal assent on 27 October 1967.”

Team Leadbeater argues that, 57 years on, there is much less need for government time, as bills are nowadays more difficult to filibuster − talk out of time. Perhaps, but there’s more concern among some MPs about whether the five hours allocated by the current leader of the House, Lucy Powell, will be sufficient to explore all the issues.

Leadbetter should also be concerned that, unlike Wilson’s cabinet, she seems faced with much more dissent, and even outright hostility from Starmer’s team. Starmer has given a pro-reform lead, but tried to stress the vote is one of conscience; some of his most senior colleagues have taken the hint.

Angela Rayner and Bridget Phillipson are two figures Leadbeater would certainly have wanted on her side, for example. Although warned off by the cabinet secretary, Simon Case, presumably on Starmer’s orders, Streeting is working on the financial impact of introducing lawful assisted dying; and that means that a “money resolution” would also need to be tabled in the House. It could be a mere formality; or a focus for opponents to argue that funds are better spent elsewhere. It was certainly not something Steel was troubled with.

It is not quite the same with assisted dying, but the emotional issues do possess the same kind of power, and the questions are similarly distressing, deeply personal and socially divisive

In the end what matters are the arguments, and the weight of opinion among the public, and, obviously, in the Commons. Like abortion in the 1960s, there is a great deal of public backing for reform, and that counts when MPs consult constituents.

Many are still undecided and persuadable. According to one biographer, Steel, a man with a cool, moderate, rational style of argument, saw that “the key to passing the bill was to retain the support of a body of middle opinion in the Commons, who did not have strong feelings about the law on abortion, and who would be frightened off if they felt they were being asked to support too radical a measure. These members − like all MPs − came under increased pressure from the bill's opponents after the second-reading debate. The large majority in favour of the bill alerted opponents to the possibility of its passing through parliament, and they marshalled their forces against it.”

As noted, at the moment it is quite feasible to take the one-way trip to the Dignitas facility in Switzerland − if you possess the means to do so. That is something Leadbeater could remind her social democratic colleagues about − because she may well not have as weighty an ally as Jenkins to deploy in the debates. Perhaps Yvette Cooper or Liz Kendall can give their friend some backup.

One last reflection, though an unhelpful one for Leadbeater, Falconer, Kit Malthouse and their fellow reformers. Reflecting years later, Steel had to concede, to himself as much as anyone else, that his abortion act did, as it turned out, make abortion far easier to obtain than was stated at the time of his bill.

By the early 1980s, his view was that: “There is a great deal of loose talk about the permissive society. We are not a less moral society than previous generations, but we do talk more openly about it. I still want to prevent the need for abortion ever arising, and because I proposed the abortion law does not mean I agree with the opinions of other people who supported it. Abortion is, I am afraid, being used as a contraceptive. The present level is too high. I agree with medical opinion that free contraception should be available [otherwise] people will accept free abortion instead because they either cannot or will not pay for contraceptives. It worries me greatly … The act says there must be a real need, and I stick to that.”

Neither, in contradiction to what Steel claimed in 1967, did what he called his reform close the debate down for good. Every so often attempts are made to change it, and the arguments haven’t been silenced − though not yet as politicised and polarised as they’ve become in America.

The term limit was reduced from 28 weeks to 24 weeks in 1990, reflecting scientific progress on the viability of foetuses, and the act was extended to Northern Ireland in 2020. That’s about it. Steel’s Abortion Act 1967, which surely changed the lives of so many women, remains the fundamental legal guide and the best moral and political compromise the nation has yet found. Leadbeater can at least take some inspiration from that and the fact it would not have happened but for the bravery of one backbencher. It can be done.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments