How big advertisement companies are taking away people’s daylight: ‘We just don’t have the resource to fight them’

‘I get five minutes of sunlight each week when they change the banner,’ says Isaac Herring, who lives in a flat shrouded by a canvas promoting an American luxury brand, tells May Bulman

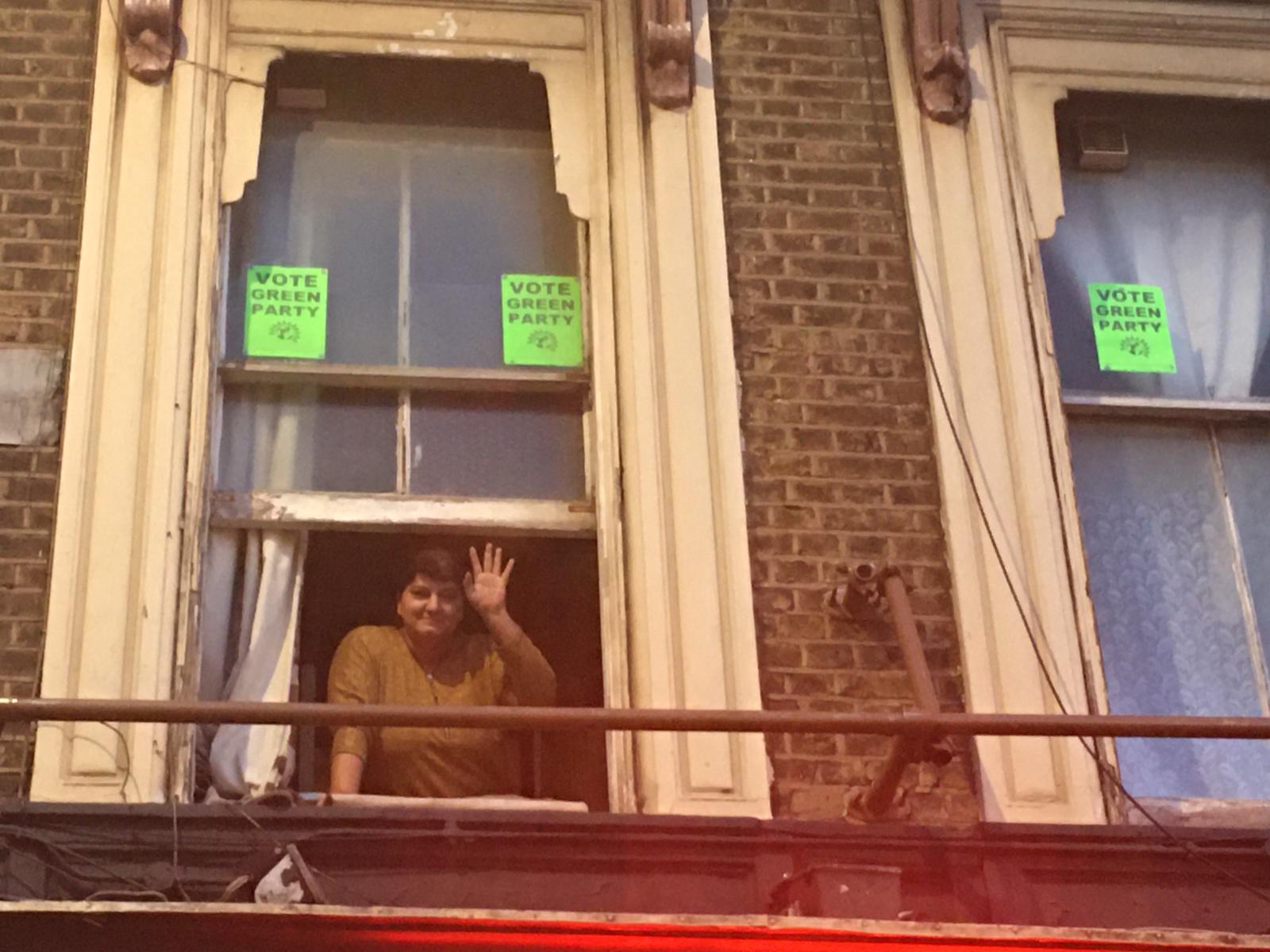

“I can see light again,” Sevineh Nazif, 42, who spent three years living in a small flat deprived of sunlight, says jubilantly. Until two weeks ago, a large banner advertising the latest iPhone was plastered across her east London home, obscuring her view of the outside world. She told how she and her disabled husband felt they were “blocked out of everything” while the hoarding was up, but that they felt powerless to do anything about it.

It was only when The Independent and others shed light on their darkened living conditions, prompting widespread claims that adverts placed on behalf of multinational companies were hiding the “brutal reality” of urban poverty, that Apple – reportedly on the orders of Tim Cook himself – promptly took it down.

As it happens, the 120 sq m “mega ad” that was daubed across the building at 600 Kingsland Road had been the subject of legal action by the local authority two years before. In 2017, Hackney Council took Blow Up Media, the firm that put it up, to court on the grounds that it did not have advertising consent, and that the canvas was therefore illegal.

This was because while the council had granted consent for the advertisement on 21 December 2015, it was valid for just 12 months, and it was granted on the proviso that the shroud frontage would allow for – and help fund – restoration work on the building. But that scaffolding never appeared to go up, and the shroud remained more than a year on.

Despite this evident breach of the original consent order, Hackney Council’s challenge was unsuccessful. Up against a large, well-resourced advertisement company with a savvy legal team, and working with planning laws that have been branded “outdated” in dealing with the current scale of outdoor advertising – the council stood little chance.

It is concerning that the hoarding across the Dalston residents’ homes was not a unique case. There are numerous other banners covering flats in Hackney alone.

Isaac Herring, a 22-year-old coder, has only ever had an obscured view from his London home. A canvas has been wrapped around his rented apartment in Shoreditch since he moved to the capital in the summer. He was told about it when he viewed the property, but, keen to get his accommodation sorted, he signed the tenancy agreement. Now, though, as a canvas promoting American luxury brand Coach obscures his view of the outside world, he questions whether it is fair for multibillion pound companies to financially benefit while he is deprived of natural light.

“They change it once a week. I get five minutes of sunlight every Sunday while they do it,” says Herring, sitting in his darkened flat on Great Eastern Street on a bright Thursday morning, the outside world looking like an expanse of smog through his windows. “There’s a white one on their now. You should see it when it’s black. There’s even less light then.”

Surprisingly, Herring says the estate agent who showed him round the flat seemed “excited” to tell him that the canvas generated profits of more than £100,000 a year for the landlord, who also receives the £1,300 a month he pays to rent the apartment. To Herring’s knowledge, he gets no rent reduction for having to live behind the shroud. But he realises he’s luckier than some.

“If there’s millions of pounds to be made, somebody’s going to do it,” he says, adding: “I don’t feel sorry for myself. I chose to live here. It’s suboptimal, but it will do, for now.”

Hackney Council says it is currently taking action on around 25 similar adverts – most of which have had some form of consent at some point, but where the consent has now expired, or where it is being breached because the ad has been enlarged to be bigger than was originally permitted.

But a spokesperson for the council also informed The Independent that court action has never been successful in getting these adverts removed, primarily due to the discrepancy between the limited resources and expertise of the local authority and the large amount of money these advertising companies are able to spend on such legal challenges.

Hackney mayor Philip Glanville says the council had been raising concerns for a while about this “unethical” practice by landlords and advertisers and that, despite the challenges, it was continuing to fight examples like this where it finds them.

“As well as more powers for local authorities to take swift action in cases like this, clearly landlords and advertisers also have a moral responsibility to consider the welfare and wellbeing of residents in placing advertisements in the first place,” he adds. “There also may be a case for strengthening the role of the Advertising Standards Authority if we keep seeing these kind of egregious cases.”

And the issue spans beyond London. Public anger over large outdoor adverts being a detriment to the local community appears to be growing.

Leigh Coghill, of Adblock Bristol, a campaign group set up in 2017 to make a stand against billboards and other corporate outdoor advertising, says change is needed at a policy level in order to effectively challenge advertising companies.

“The regulations are out of date,” she explains. “We are seeing a massive increase in the number of companies trying to dominate public space, and a massive rise in the lengths that advertisers will go to, and new avenues that haven’t been explored, to do so. There have never been regulations written for this sort of thing.”

People working in the outdoor advertising industry say there are a number of “big players” that are flouting planning regulations when erecting banners, but that councils – particularly in London – “just don’t have the resources to fight them”, describing them as “toothless”.

An industry insider, who did not want to be named, says: “Councils used to have teams of people out there looking for bandits. I think now they’ve shrunk their departments so much that most of their planners … may have a planning degree, but they actually don’t really understand UK planning. They just don’t understand their own rules, that’s the problem. It’s about lack of funding.”

The landlord of 10 Great Eastern Street said he was unable to comment because specific details of commercial arrangements and/or contracts remained confidential between the parties.

Blow Up Media declined to comment.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks