2013 - the year in review: A year full of sound and fury, signifying what?

It was a year of storms in teacups; but also of real storms, meteorological and metaphorical, that actually mattered

If you are groping for some way of thinking about the news in 2013 that will seem less than completely arbitrary, start with two storms. The first hit the UK on October 28. Popularly known here as the St Jude storm, it was a squabble before it was even a squall: a Berlin meteorological institute named it “Christian”, a Swedish rival “Simone”. The European Windstorm Centre called it “Carmen”. The Danish Minister for Climate dramatically overruled his national weather experts’ exciting choice of “Oktoberstormen 2013” with his own preference for plain old “Allan”.

Whatever its name, it aroused enormous anticipatory excitement in the British press. This would, it was suggested, be the biggest storm since 1987 – and, the Daily Express predicted, “one of the worst storms in history”. Havoc could be confidently expected to ensue, and so it did. The Daily Mail ran a full spread of pictures of trees on top of cars, and fearlessly reported on the ANGER AT GARY LINEKER’S TASTELESS STORM TWEET. Somehow, Lineker clung on to his job. On the Today programme, Michael Fish chimed in. “I had a phone call from my wife and of course it was my fault that a tree has apparently gone down in my garden,” he grumbled. “So even I don’t escape.”

Thus the storm in a teacup. On the other side of the world, about a fortnight later, a real storm was coming. This time, the baroque disputes over nomenclature seemed somehow less important. Typhoon Haiyan, or Yolanda, struck the Philippines with catastrophic force. The cost to the country’s economy was about $15bn. About 4 million people lost their homes. By the beginning of last week, 6,057 were thought dead, with another 10 or so being added to the count each day.

We didn’t ignore it, exactly. Three newspapers put a picture on their front pages, for one day. Did we really care, though? Well, there are better indices of our level of interest than the newspapers we are presented with. And such measures suggest that our concerns are at least a little parochial. At the peak of Typhoon Haiyan, for example, we Googled the relevant words only a quarter as much as we did the comparable terms when St Jude – or, if you prefer, Allan – was at its worst.

You wouldn’t want to be too sneeringly judgemental about all this. St Jude killed at least four people, and it did a great deal of damage. It might in any case be argued that it is more useful to search for the storm that is about to hit you, and from which you may need to protect yourself, than it is to ogle disaster-porn from the other side of the world.

And yet the comparison seems apt: 2013, we were told – by the Oxford Dictionaries, no less – was the year of the selfie. If you find the concept that it was the year of any one thing to be vapid, well, that’s sort of the point. The selfie – which must be shared with someone else if it is to be conceptually complete– is a mode of communication whose only meaningful content is the message: I AM HERE. (Sometimes it may also say, AND I HAVE A TAN.) This was the year of Haiyan, of Huhne, of HS2; of Paxman’s beard, and Brand’s confusing call to arms; of Syria, and of Snowden; of a new pope, and a buried king, and a dead prime minister. It was the year, for God’s sake, of Ruby Tandoh. But the selfie says: whatever. On the back of my phone, I have a camera that’s better than Henri Cartier-Bresson’s, and I could use it to document sunsets or revolutions; but I choose to use the one on the front, because I AM HERE. The storm may be in a teacup, but it is my teacup. These are my hot-dog legs. This is my year.

In 2013, this is how the news divides. There are the stories that we attend to easily, into which we can insert ourselves as character or opinionating chorus. And there are the stories which are harder – which may matter more, but which seem to be impermeable, stubbornly resistant to interpretation or sympathy.

The stories of the year

Let's start with the easy ones, since that is where we all do start, and where is easier than a royal baby? Actually, quite a few places. It might have been an easy story to consume, but it was a hard one to produce. Pity the rolling news presenters, camped outside a hospital with only three facts – gender, name, arrival time – in play, and no information on any of them, for hours and hours and hours. Sky’s indomitable Kay Burley was there for 30 in two days.

Perhaps mindful of the risks entailed in the Daily Mirror’s premature IT’S A GIRL! splash, journalists on the scene took no risks. “I think the chances are they’ve got a shortlist of names,” one BBC reporter said. “I think they’ll probably go for something quite traditional.” “All I can safely say,” another solemnly added a littler later, “is that it will be either a boy or a girl.” Anchoring proceedings, Simon McCoy kept Auntie’s reputation for accuracy intact with his summary of the situation: “Never have so many people gathered together in one place with absolutely nothing to say.”

It was, at least, good news, even if you were an ardent republican: however strange it was that he was clad in a full length adult woman’s dress for his christening photos, George – blissfully unaware of the life of gilded servitude to which, no matter his capacities as a molecular biologist or a stand-up comedian, he is already fated – did look awfully sweet. And as the future king sat crapping himself, the nation reeled from the agglomeration of good news. England were winning the Ashes; a Briton had just won Wimbledon. It is tempting to wonder if either will happen again before the little blighter ascends his throne.

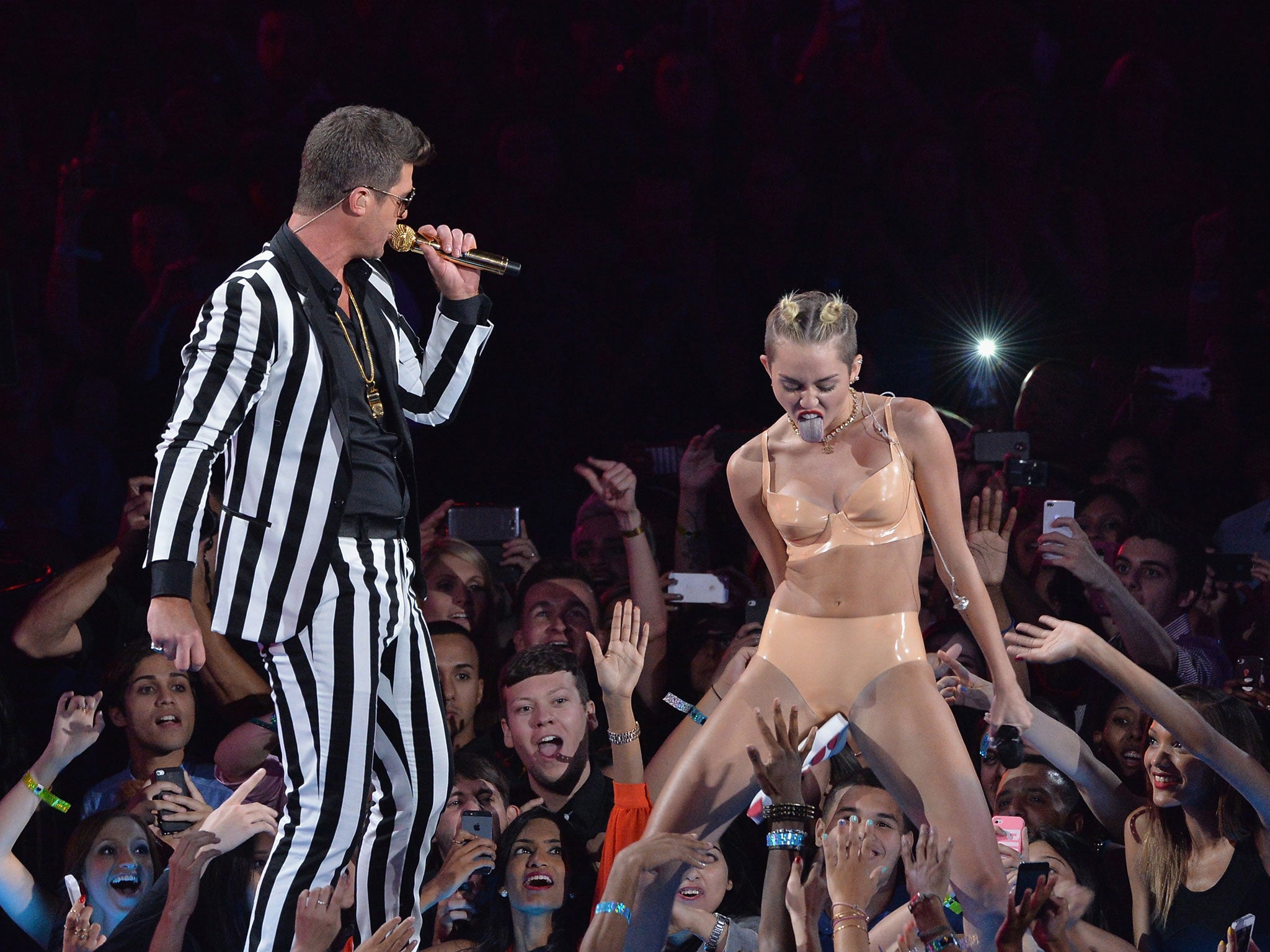

You should skip the next paragraph if you have problems with the concept of “twerking”. I will not mind.

We had to cling to that good cheer. So much of the other froth was poisoned. The infantilised sexpots of the “Blurred Lines” video reconfigured Robin Thicke’s irresistible tune as the sort of thing you might hear blaring from a paedophile’s ice cream truck. That unease only grew when you saw former child star Miley Cyrus twerking “on” him at the MTV awards and learnt how seedy an innocent preposition could be made to seem. The impossibility of imagining the roles reversed in either scenario was a neat summary of the state of sexism in 2013.

On this side of the Atlantic, things were no brighter, unless you enjoy seeing celebrities humiliated in court, which a lot of people do, of course. You briefly put yourself in that tribe when you saw Chris Huhne and Vicky Pryce as characters in a farce and then, when you saw the impact on their children, you felt horrible, and realised that in fact they were starring in a tragedy; #teamnigella or not, the kind of play Ms Lawson is in is not yet clear, but she seems some way from a happy ending. The gleeful response to the bombshell of Andy Coulson and Rebekah Brooks’s affair turned even the solemn story of phone hacking – one which you thought had had all the sex sucked out of it in 2012 – into a prurient and ironic exercise in tabloid voyeurism. I can’t remember a year when following the news has required you to be so persistently invasive.

On it went. Justin Bieber left his pet capuchin monkey in Germany, and still owes the Berlin authorities £7,000 for their trouble. Fully 367,000 people retweeted One Direction’s Niall Horan when he made the profound observation that it was his birthday, which, I will note with total equanimity, is almost exactly 1,000 times as many as retweeted an excellent joke that I made about Benedict Cumberbatch.

Shortly after the emergence of Tinder, a lot of people you know’s Facebook pictures became mysteriously more flattering. The 23-year-old owner of Snapchat, which is yet to make a single penny in profit, turned down a $3bn bid from Facebook, so either he is crazy or the universe is. They found Richard III’s skeleton, and would not stop going on about it.

Sometimes the patina of bulls**t would be so wearyingly familiar that you would dismiss a story as a frippery before realising with a start that it might actually matter a little. Angelina Jolie wrote about having a double mastectomy, and her courage in doing so was sufficiently inspiring to make the ensuing commentathon bearable for maybe an hour. Tom Daley used YouTube to tell the world he had a boyfriend, and in the year that politics finally caught up with reality and legalised gay marriage it seemed like a minor milestone, even if his Union Jack cushions were terrible.

Read more: 2013 in review

It took his death, but the world came together for a moment for Mandela

Very public justice for Chris Huhne and Nigella Lawson

The battle for the 2015 election started two years early

The year the NHS took a serious kicking

What a contrast between the optimism of the Arab Spring and the dark mood of today's Middle East

Obama's foreign policy and the birth of a kinder, gentler nation

Timeline of major news stories

The best TV of the year

The best pop music of the year

The best theatre of the year

The best films of the year

The best comedy of the year

The best books of the year

Fashion was at its best when it was boldest this year

Is there life on Mars? watch this space

Obituaries 2013: Those who left us in 2013

Two Ashes series, a second Tour de France... and a Wimbledon winner

It seemed impossible that Plebgate mattered, but it really did. Caroline Criado-Perez’s campaign to get Jane Austen on a banknote was mostly a talking point, a small battle in the war over feminism; her fearless response to the Twitter torrent of threats and abuse she received for her trouble turned into a rather larger one. And the world stopped when Penguin agreed to publish Morrissey’s autobiography in its “classic” imprint. Actually, that one probably was bullshit.

If there’s a philosophical question to be answered about whether something starts to matter if enough people are interested in it, the opposite is not the case: some things matter whether or not we pay attention. Syria mattered all year long, just as it did for all of 2012, just as it will for all of 2014. It was so unremittingly awful that it was hard to know where to get your hooks in. In August, a gas attack on a suburb of Damascus killed hundreds of people, perhaps as many as 1,700.

In the context of a war that has already killed more than 100,000, this particular atrocity might still not have cut through. But there were pictures, and videos, that you didn’t want to look at, and could not look away from. The most appalling report I’ve ever seen on the BBC News at Ten showed a milky-eyed child convulsing on the floor, apparently under the influence of poison gas. The Daily Mirror used a picture that might in other circumstances have been adorable: nine infants, their eyes peacefully closed, under what looked like a blanket. And then you realised that they were packed in ice.

It was the pictures that made it stick; that day was the beginning of a process that nearly ended up in western military action. That it didn’t is not a subject for non-expert commentary, really. But as David Cameron made his triumphant appearance in Helmand earlier this month, it was hard not to think that, if that Mission really had been Accomplished, we might have been rather more likely to countenance a Syrian intervention.

To find a way to make things matter is an indispensable political skill. Ed Miliband, who has rarely shown the knack in the past, managed it with the deeply unsexy subject of energy costs, and his proposed price freeze. No one could quite do it for HS2. Snowden seemed like a pure abstraction until you realised that the NSA genuinely might be spying on you; if you had any doubts as to the story’s significance, they quickly faded when you saw how angry the whole business was making Louise Mensch.

The American government was accused of bugging Angela Merkel’s phone; “spies spy”, sneered the non-eventers, opening up the possibility of a new legal strategy for habitual petty thieves.

And, every once in a while, something would happen that both mattered and compelled our attention at the same time. It seemed wrong that Reeva Steenkamp’s appalling death drew us in only because of the identity of the man who killed her, but the tragic heft of that story – and of the extraordinary courtroom pictures of Oscar Pistorius, a hero left utterly alone by the weight of his actions – was unmistakable. The imprisonment of the Arctic 30 by the Russian authorities drew the outrage of anyone who cared about the environment, or civil liberties; it remains to be seen whether our close engagement with the disgrace of Vladimir Putin’s justice system remains when the targets are from Murmansk.

The Boston bombing was an appalling reminder of the power of social media to tell a story quickly; I’ll never forget that image of a spectator, Jeff Bauman, staring in disbelief at the maimed stump where his leg had been. The aftermath, meanwhile, was a similarly appalling reminder of just how useless an online mob can be. No apology to the family of Sunil Tripathi, falsely accused by amateur sleuths as he lay dead in the Providence River, could ever be enough.

About a month later, something happened which made the methods of the Boston attackers seem grotesquely quaint. The attack on Lee Rigby was a perfectly modern piece of terrorism, sinister above all in its technological opportunism: it was easy; it was small; it was caught on video, and the video went round the world.

Those pixelated images of Michael Adebolajo carrying a meat cleaver and a knife in his bloodied hands made you marvel at the nerve of the bystander who filmed him, amenable though his subject was. This preposterous piece to camera, climaxing in the inaccurate vow that “you people will never be safe”, seemed like the ultimate act of egomania, the culture that spawned the selfie spiralled atrociously out of control.

The smallness of that act – a smallness of imaginative sympathy, and of ambition – was, like so many of the other small events that made up the year, thrown into sharp relief by another death. Nelson Mandela’s was far from the only significant obituary: the passing of Thatcher seemed simultaneously to end an era and to open it to debate once more, and the world will miss the likes of Doris Lessing, David Frost, and Peter O’Toole.

But Mandela was different. In an era of crises, environmental and economic, that seem so overwhelming that the only answer is to retreat into triviality, the retelling of Mandela’s life was a reminder of another way to be.

Still, whenever we could, we made it trivial. We called him Madiba even if we’d never met him, trumpeted his achievements as a political no-brainer even if we’d disdained them when it mattered. At his memorial service, an extraordinary event only subsequently made a bit weird by the revelation that the sign language interpreter was all fingers and thumbs, tens of thousands of people evaded that sort of egoism for a bit.

Who reminded them of it? Our leaders, of course. Looking out at a spectacular sea of humanity giving thanks for the life of one of the greatest men of the twentieth century, they turned the smartphone camera back upon themselves.

RIP, Nelson Mandela. WE ARE HERE.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks