Will Cornick: The boy who killed his teacher, and a conundrum for the prison system

When children are locked up for murder, the aim remains ultimately to rehabilitate them back into society, even if that means a change of identity. But the case of Will Cornick presents a challenge never before faced

Even within the tiny file marked ‘schoolboy killers’, Will Cornick is an oddity. He came from an apparently loving home, he was intelligent and an academic achiever, and not subject to the detailed scrutiny of social services because of years of teenage run-ins with the authorities. He had no criminal record.

How he came to murder Ann Maguire – a popular teacher at his school, against whom he held a murderous grudge – remains a mystery to his family and those closest to him.

What to do with the 16-year-old murderer will now exercise social workers and the prisons system for at least the next 20 years. He might never be released from jail and his prospects, should he ever be – based on the evidence of past cases – could be grim.

The naming of Cornick, and the length of sentence that he received, was criticised yesterday by campaigners for youth offenders who said they would see him detained for decades in a system ill-suited for rehabilitation.

“I don’t think a child – and he was a child – should get a life sentence because they are young, their brain is not mature and a life sentence is indeterminate, it could last forever. I think no other western European country would impose a life sentence on a teenager,” said Penelope Gibbs, who chairs the Standing Committee for Youth Justice (SCYJ), an umbrella group of charities and campaign groups.

“Do we want him to be rehabilitated? Do we want him to leave prison with the lowest risk possible of causing more harm to others? Yes. How long do we need to achieve that, rather than how long do we need to punish him for? We do need to punish him but I think to punish him for longer than he’s been alive for is disproportionate.”

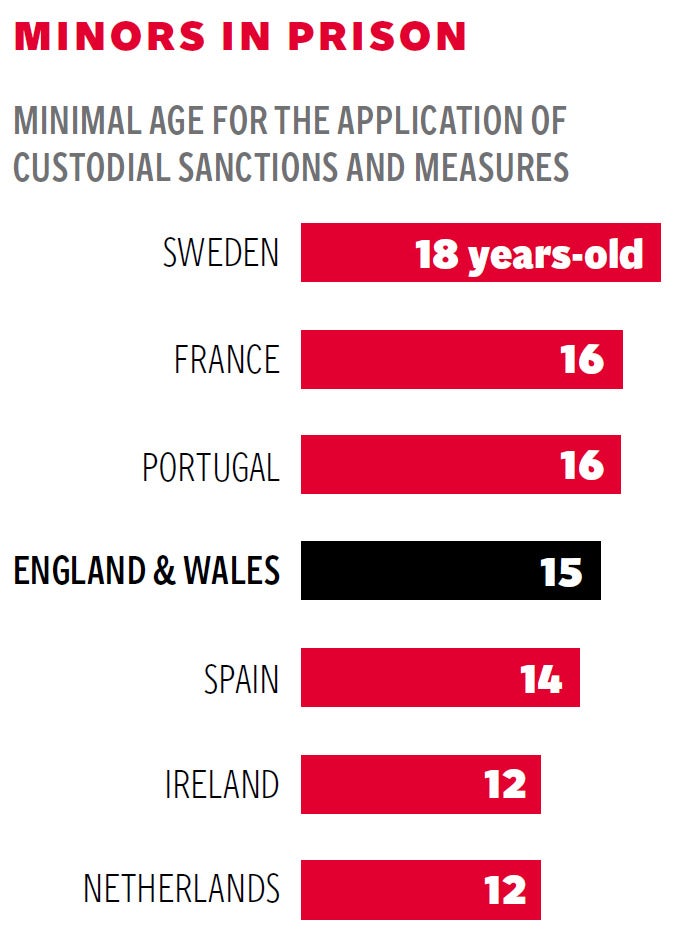

He will be one of just 16 other children in custody for murder in a detention system that houses more children – more than 1,400 in the UK according to 2012 figures – than any European nation other than Turkey. Britain is considered to have one of the most punitive systems for children in Europe with the lowest ages of criminal responsibility of ten in England and Wales, and eight in Scotland.

Only Switzerland has a comparable age of responsibility, according to a study by the Council of Europe. Even so, the number of young offenders has been slashed from more than 3,000 six years ago after a change in police targets culture that saw teens picked up as a matter of routine for minor offences to boost clear-up rates.

Cornick could now be detained in a secure children’s home, which tend to be for the most troubled and damaged youngsters. The home was the initial destination for the two 10-year-old boys convicted of murdering James Bulger on Merseyside in 1993.

Alternatively, he could go to a specialist unit at a young offender’s institute – such as the Keppel Unit at Wetherby prison that was described in a prison inspector’s report as a model for the treatment of young offenders. It holds about 48 children aged 15-18 who were some of the “most challenging and vulnerable” people in the country but is the only one of its kind in the country.

It is clear that any attempt to rehabilitate him will be a monumental task. After the attack, he told psychiatrists he “could not give a shit” about the grief of his victim’s family. “In my eyes, everything I’ve done is fine and dandy,” he told experts.

He is unlikely to get the academic stimulation of his previous studies. Cornick could be taught in a class of around eight people with a focus on basic literacy, numeracy and vocational skills to get a job when they were finally released. He took and passed five GCSEs a year early, but he will be unlikely to be able to study for higher level qualifications now.

Harry Fletcher, a criminal justice expert and director of the anti-online abuse charity Digital Trust, said: “I think that the judge really had no choice but to give him a lengthy sentence, because the possibility of him voluntarily taking part in any rehabilitation processes at the moment is really rather slim.

“He’s been on remand for quite some time and all the people who work with him say he hasn’t shown any remorse at all. Given the sentencing guidelines, the judge’s hands were fairly tied.

“The notion that he might never get out I was surprised about, because who knows what he’ll be like in 20 years? He may have come to terms with it, be grief-stricken – we just don’t know. But it is going to be extremely difficult to manage him, given that he is saying it was justified. It’s possible that he will develop a full-blown personality disorder, which will mean rehabilitation is extremely difficult if not impossible.

He added: “On the other hand, he might be working with therapists, psychologist and psychiatrists with whom he can bond, and that improvements are made. But pre-meditated killing at 15 – you don’t want to damn him now as having no hope, but the prospects aren’t brilliant.”

Children involved in the most grave of crimes have tended to be highly damaged individuals, with a long history within the care system and underlying mental health issues, said the Howard League for Penal Reform.

“Custody does nothing to help that and everything to exacerbate these issues,” said Andrew Neilson, head of campaigns for the charity.

“First and foremost, custody is about security and locking people up and rehabilitation is second, particularly in the current context within prisons where budgets have been slashed.”

The fate of previous high-profile cases reveals the difficulty of rehabilitation given the notoriety of their crimes.

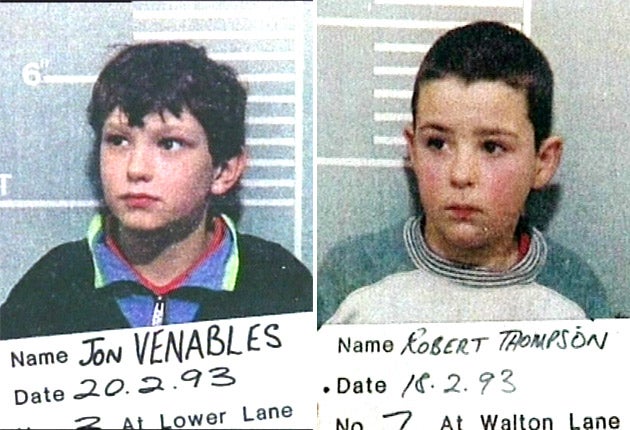

The young killers of James Bulger – Jon Venables and Robert Thompson – were both named and pictured after they were convicted of his murder as 10 year-olds. They had lured the two-year-old boy away from a shopping centre, took him to a railway line and beat him with bricks and iron bars.

When he was given a new identity on his release from a secure children’s home in 2001, Venables was rearrested after breaching the terms of his parole by visiting Merseyside.

He developed drink and drugs problems and revealed his real identity to friends. He was jailed for two years in 2010 for downloading and distributing indecent images of children. He was released again in 2013.

Mary Bell, who secured notoriety in the 1960s for killing two children at the age of 11, successfully applied for lifelong anonymity in 2003 despite collaborating on a book. She had assumed a number of different identities and had moved more than five times after people discovered who she was.

It is impossible to know whether Cornick will come to regret his crime in 20 years time, but the stories of Venables and Bell suggest that it will not be forgotten in his lifetime.