Whatever happened to London's knife-crime epidemic?

Twenty-one young people were stabbed to death in London in 2008; in one 24-hour period in July, six people were stabbed to death. Archie Bland saw one of the victims die on a street in Tufnell Park. He looks back at that terrible summer when it seems that our national fear of knives reached its zenith

It was the blood I saw first. First an irregular spatter from the pub to the minicab office, where, I now saw, an urgent little circle had formed around something on the pavement. "Keep pressure on it," I heard people say as I approached, "You have to stay still". The object, it turned out, was a man. And then: the spatter becoming a livid drip at the curb, and T-shirts and tissues so sodden that they were no longer any use to stop the flow. And a wine-dark agglomeration at his neck.

It's five summers since I saw him die, and I still can't really believe it. It was about three in the morning, and I was drunk after a house party in Tufnell Park, a neighbourhood in north London that at the time I barely knew. I had come round the corner to a bus stop at the busy junction near the Tube. It took me such a long time to figure out what was going on.

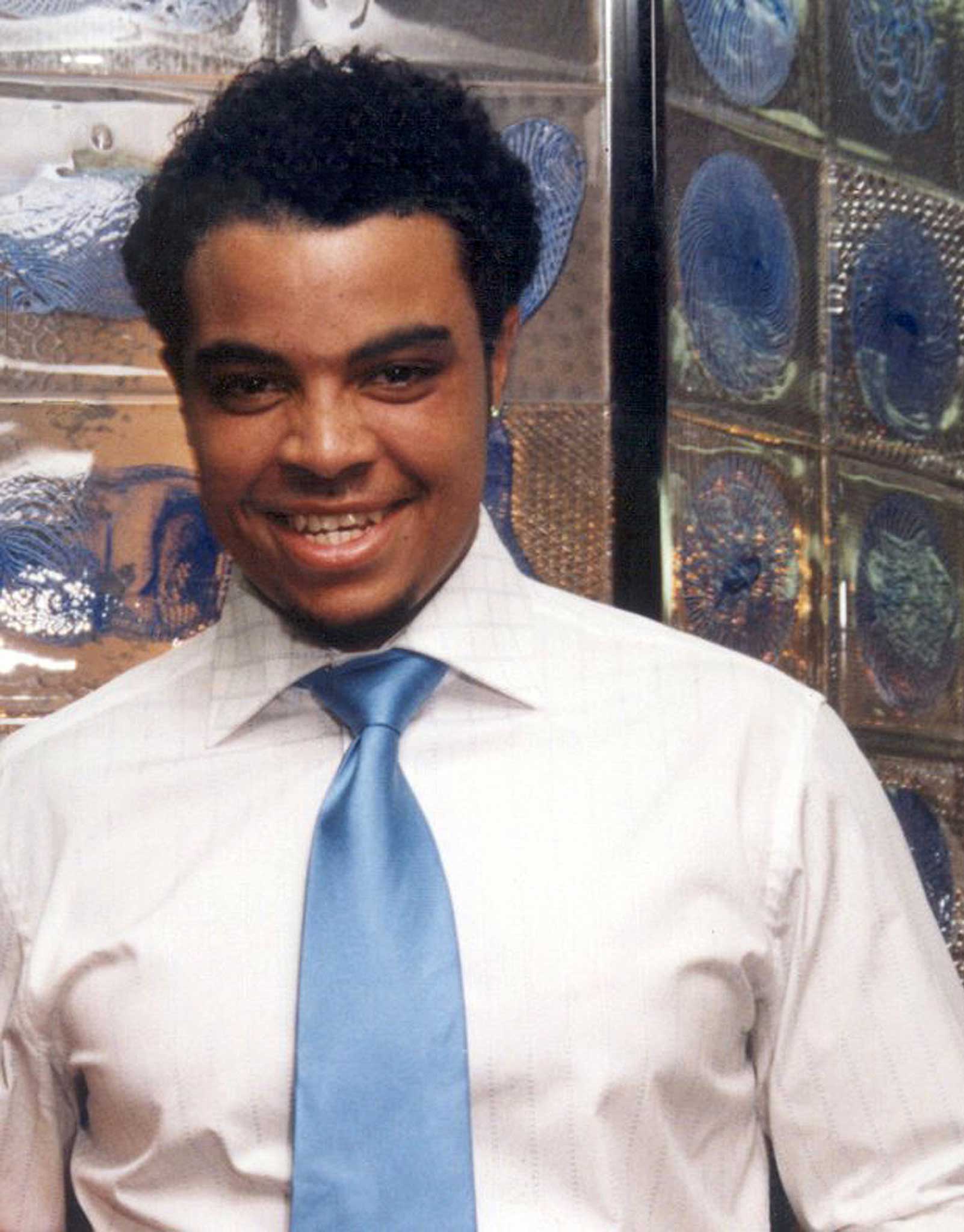

The man who lay there on Dartmouth Park Hill, his arms groping for a lifeline that would not come, had grown up a few streets away. His name was Elliot Guy. He was strong, but, by all accounts, not one to start a fight; he was energetic and ebullient, and at least three people considered him their best friend. He was 27 years old. Three months earlier, his partner, Amy, had given birth to a little girl they called Eleanor.

The new family moved to Ealing. Before, Elliot had worked as a carpenter on building sites, but he got sick of the early mornings and long hours and limited prospects. He developed a bad cough, and the doctor told him that the dust he worked in every day was damaging his lungs. He and Amy agreed that he would retrain as a cabinet-maker. The 12-month course was in Devon, where Elliot lived in a caravan, away from his friends and family; that weekend, he was celebrating being back home at last.

The next night, Elliot was planning to go to the Lovebox festival in east London. But on that Friday, he was just happy to be in his old neighbourhood. He, his cousin, and a friend had gone along to a party at a flat on the Fulbrook Mews Estate, just around the corner from Dartmouth Park Hill. The party, according to later court testimony, had a "nice atmosphere", and there is no indication that Elliot did anything that might be considered a provocation. At about a quarter to three, he went to the bathroom. As he washed his hands, Colin Welsh, a schizophrenic with a history of violence who Elliot had never met, broke through the door and stabbed him in the neck.

Some of this I learnt over the next few days in July 2008; some of it I learnt last month. That evening, all I or anyone else seemed to know was that with every minute that passed, the life was ebbing from this nameless man. After a helpless wait, the outraged shriek of a siren came. People said he was doing really well, he was doing brilliantly, he was going to be fine, they would be here in a minute, just hold on, just please stay still. He looked like he was trying to get up.

The paramedics arrived, and got him on to a gurney, and gave him oxygen. But he wouldn't rest. "You've got to hold still, mate, or I can't keep the pressure on it," one of the paramedics said. It was no use. He kept moving. "His efforts," I wrote the next day, in a piece which now seems altogether too purple, "had a desperate knowledge about them, a hopeless instinct in the face of an implacable, permanent fact." He made terrible sounds. The hospital said that he died about an hour later, but as the ambulance pulled away, he already seemed to be gone.

Reluctantly, the group dispersed. Forgetting my bus, I wandered away, and then bumped into friends leaving the same party I'd been to. We shared a cab. As we drove off, we passed flowers heaped at the spot on York Way where another knife victim, Ben Kinsella, had been killed a few weeks earlier. His funeral had been that afternoon. When I woke up the next morning, I saw that The Independent had splashed on Deborah Orr's account of the stabbing of her neighbour, a teenager called Frederick Moody. He had been killed, it was later reported, after a water pistol fight.

What ever happened to knife crime? To me, that weekend in 2008, now so long ago, felt like the moment that our national fear of knives reached its zenith. Twenty-one young people had been stabbed to death in London that year; in one 24-hour period in July, six people were stabbed to death, and in an otherwise slow summer, a story that was already smouldering caught fire. More than 1,000 people joined the families of Elliot Guy, Ben Kinsella, and others to march across London in protest at the violence. Across England and Wales, 267 people were murdered with knives in 2007/08, after 272 in 2006/07 – the worst numbers in the 30 years that the statistics had been tracked. The press spoke fearfully of an "epidemic". 'Blade Britain', one front page of the Daily Mail called it; the next week, another was headlined 'Knives: why no part of Britain is safe'.

You could see why people were nervous. "You read about it in a way that you don't if you open the papers today," says Richard Garside, director of the Centre for Crime and Justice Studies. "There was a degree of reporting that there isn't now. And perhaps, in part, it was because it was the summer and people were looking for things to report." One way of assessing the effect of that glut of stories is to ask what we looked for online. According to Google Trends, the period from June 2008 to March 2009 saw a huge spike in the number of searches for the term 'knife crime'. In July 2008, there were about 10 times as many searches for the phrase as there were in February this year.

And yet while the number of knife murders and the whiff of crisis might have been at an all-time high, those observations don't tell the whole story. While there are myriad statistics available to paint whatever picture you want, most criminologists agree that violent crime has been in persistent decline since the mid-1990s. "If we believe those data," says Garside, "the question becomes: why is it that at particular points we become more concerned about an issue? It might be a signal moment, a signal offence, and then as soon as there's another we cry, 'Oh my goodness, it's out of control'. There's an amplification there. But your risk of violence by a stranger hasn't changed at all." Indeed, the knife murder figures are a small enough fluctuation from the norm that they might simply be a random spike – a piece of statistical misfortune, and nothing more. If we were concerned about knife crime then, we should probably be concerned about it now.

The walk from the spot where Elliot Guy lay on Dartmouth Park Hill to the corner of North Road and York Way, where Ben Kinsella was attacked, takes just over 10 minutes. About 100 metres before you get there, you pass Aspendos Bar and Grill, where, in the very early morning of 29 June last year, a 20-year-old criminology student called Mohamed Abdullahi was stabbed to death. Last month, three young men – Dean Winston, aged 20, and Calvin Collins and Kyle Sober-Froud, both 19 – were sentenced for the murder.

On the same night Abdullahi died, someone had carried out a drive-by shooting on Winston's nearby home, when his autistic younger sister was there on her own; the three young men had come to the view that Abdullahi was responsible. In fact, he was not – phone records prove that he was elsewhere at the time. All the same, Winston and his cohorts were out for blood. Armed with knives, they found Abdullahi at the kebab shop and dragged him into the street. Then they set upon him in an attack, recorded on CCTV, that the judge who gave them sentences of between 23 and 24 years called "primeval". They stabbed him twice in the buttocks and once in the heart. Within 70 seconds, he was dead.

On the last day of the case in an Old Bailey courtroom last month, the public gallery was packed with members of all four families affected, with more waiting outside. The prosecutor read out a statement from Mohamed's father Aydarus. "It is so very difficult to explain the loss and sadness we feel," she read. "It all seems so senseless and unnecessary." When she came to a passage detailing the impact on his six sisters, one of them gave a stifled sob. The least engaged people in the room appeared to be the three convicted men, who fixed their gaze to the floor. As they all filed out to begin their sentences, they sniggered as they went. There was something obstinate and pathetic about this tiny display of defiance. I had only noticed one moment when it was punctured: when Kyle Sober-Froud, hearing his name as the judge turned to his case, sat up a little straighter and opened his eyes wide. He seemed like a schoolboy waiting to learn how he did on a spelling test.

I live in Tufnell Park now. I love the area, and I have never, for a single second, felt threatened. I'm writing this in a cosy little café on the local high street, which I am careful to frequent rather than the Costa across the road. When I remember, I use the Turkish grocers instead of Sainsbury's, and get a little glow of local wellbeing. I feel bad about the way that, as property values rise, every expiring lease seems to mean a longstanding business ousted for a pastel-fronted replacement that feels like it belongs on Primrose Hill – a chic homeware shop, a luxury ice-cream parlour, the sexiest butcher's I've ever seen.

Next door to the flat where Colin Welsh attacked Elliot Guy, a new-build development of 25 flats called 'The Junction' has since gone up; a one-bed sold at the end of last year for £394,000. I'm not sure what to make of the offers I've had to rent my flat for a month or two from well-to-do parents desperate to get their kids into the outstanding primary school nearby. I keep seeing Damian Lewis.

"It's a desirable place to live now," says Richard Osley, deputy editor of the Camden New Journal, who has reported on the area for more than a decade. "You've got Gavin Esler living next door to Neil Kinnock, Giles Coren, Alan Rusbridger. It's expensive now. There's this strange thing where you've got council estates still there and they'll never be sold off, but they're next to really posh houses, with not much in between."

Mohamed Abdullahi lived on the street that adjoins mine. The drive-by that so enraged his three killers happened a couple of minutes away. A few weeks ago, on the first warm day of the year, I walked past Ruby Violet – 'ice-creams and sorbets hand made in Tufnell Park... local, fresh ingredients churned with 100 per cent organic milk'. I found it hard to connect the place to the idea of a shooting so nearby. "Not everything is lovely round here," says Osley. "There are still teenagers stabbing each other, rivalries across postcodes. I guess if you're one of the better-off people in the area and you see all these fancy restaurants, you don't see it. But, in fact, things are happening on every corner."

This points towards another possibility: that the concern over knife crime was never borne of the fear of violence, exactly, but was instead an expression of a different anxiety. The truth is, many parts of Britain are safe, and many of the 'dangerous' parts are safe for most people. But even as the general rate of violent crime has fallen, the demographics of those committing it have skewed younger and ever more urban. In 2008, when teenager after teenager – often black – was reported as the victim or perpetrator of knife crime, a new subject for public concern emerged, prompting liberal handwringing and reactionary racism in equal measure: gangs, gangs facing a crackdown on guns, gangs involving younger children than ever before, gangs where carrying a knife could bring you respect.

Gangs are still a huge problem. In London alone last year, they were responsible for 22 per cent of all violent crime, and 17 per cent of stabbings. The figures for other big cities are comparable. And according to Dr Simon Harding, author of The Street Casino, a forthcoming book about gang culture, if anything it's getting worse. "There has been an evolution," he says, "in gangs and how they work. The level of violence wasn't always as high as it has been for the past six or seven years. Now they're rapacious."

In this context, he adds, the presence of knives is all but inevitable. "In the logic of the gang today, carrying a knife is as much a requirement as carrying a smartphone if you work in the city. It's about chasing what I call 'street capital' – and stabbing someone will elevate it very, very quickly. Monitoring your capital, protecting it, makes you hyper-vigilant. And that's why you end up with people stabbing their mate if he looks at them the wrong way."

Outside, after the sentencing in the Abdullahi case, Dean Winston's mum Barbara leaned against a wall and insisted on her son's essential goodness. "There's no justice at all," she said. "He never attacked anybody before. He's always helped with his sister. If it wasn't for him I'd have had no life." Her hands trembled as she lit a cigarette and she waved me away. The family has had to deal with catastrophe before. Dean Winston has two previous convictions for possession of a knife. And in 2006, his half-brother Tommy was stabbed to death after he detached the seat of a close friend's scooter and hid it. He, too, died on York Way, about 100 metres up the hill from where, seven years later, his sibling would take another life.

Back in the summer of 2008, the Metropolitan Police, with Boris Johnson's approval, reacted to the knife problem with Operation Blunt 2. The approach was centred on the use of stop and search, and its effects are much disputed. While the then-deputy mayor for policing, Kit Malthouse, attributed a 7.9 per cent fall in knife crime in 2008 to the seizure of 8,000 knives and 16,000 arrests, critics such as Kent University's Professor Marian FitzGerald analysed the figures by borough and argued that any apparent correlation was a mirage: between April and October 2009, she pointed out, knife crime fell by 24.8 per cent in Islington, where 840 searches were carried out – and rose by 8.6 per cent in Southwark, where there were more than 9,000.

Richard Garside suggests that this evidence chimes with the general shortcomings of the crackdown that typically follows any such visible burst of violence. "What tends to happen is that politicians reach for the policing lever," he says. "We have crackdowns and arrests but there is really no evidence that they are effective when the underlying reality is ignored. We need to decentre the police as a way of tackling it."

Sure enough, now that public attention has moved on and the debate can be conducted at a somewhat lower temperature, the police themselves acknowledge the necessity of a more rounded approach. One significant adjustment has been the February 2012 relaunch of Trident, the operation devoted to tackling gun crime in London's black community, to take on gangs more broadly. "We invested heavily and we changed our strategy," says Commander Steve Rodhouse, the Met's head of gangs and organised crime. "We identified the most harmful gang members, and we approached them to give them a choice – leave that lifestyle, but relentlessly enforce the law for those who continue to offend." In the first year of the new strategy, Rodhouse says, reported stabbings fell by 28 per cent.

That approach is based on Ceasefire, a model used with considerable success in the US. The same idea has been applied in Glasgow, where groups of 40 or 50 guys are summoned for a meeting called a 'call-in'. They hear the story of someone affected by youth violence, and they are given a stick and a carrot: a warning that if such violence continues, every member of the gang will find that the police make their lives hell; and a pledge from a range of charities and agencies to provide help with education or finding a job. Over the first three years the scheme was in place in eastern Glasgow, violent offending among those who got the ultimatum fell by 46 per cent.

The Kinsella family, meanwhile, have tried to find something positive in the death of their son by running an exhibition about the consequences of knife crime. First opened in Finsbury Park, it's now running at Millwall Football Club; the children from local schools who attend are shown a video about Ben, and the consequences of his death. They have a few of the myths about stabbings – like the idea that there are 'safe' places to stab someone, as a way of sending a message without costing a life – dispelled. Then, by looking at a comic strip with a series of possible outcomes, they are invited to think about the chain of poor choices that can lead someone who might never have considered themselves violent to use a knife. "We have kids coming in who've lost a cousin, or a brother, and you can really see how devastating it is," says Abby Kegg, who runs the exhibition. "We're trying to show them that you always have another option."

If knife crime has slipped off the public agenda, such efforts may ultimately help to justify its newfound obscurity. But they will be of scant consolation to the Guy family: the attack by Colin Welsh (who was jailed for life in 2010 for manslaughter) would not have been averted by better community work. Elliot's death, coming as it did in utterly random fashion, stands in opposition to the depressing cycle of gang violence and fear that so often sparks knife crime, although when the news emerged about a mixed-race guy at a north London house party, many assumed the opposite. His family declines to speak to me for this article, but a close friend says: "He was never off the rails. He would never look for trouble. We never knew anyone who carried a knife. At a party he might get noticed because he was so big, and that could be good or bad. But he was a big happy guy."

Although he had never carried one in anger, Elliot had seen knives and their consequences at least a couple of times before the day he died; once in a mugging on Hampstead Heath, another time when he bumped into a friend in Camden whose hand had been cut. "That's what I thought was going on when I heard he'd been stabbed," the friend says. "I thought we'd be going to the hospital saying, 'Oh, you idiot, getting stabbed in the hand 'cause you think you're a badman', that sort of thing, taking the piss out of him. And I really didn't take it seriously at all."

Elliot's death left an enormous hole. "So many people loved him," his friend says, and it's clear that his absence has revealed the ways that he knitted groups together that no one quite realised until he was gone. Although his stabbing was atypical, it is like them all in the most critical and terrible way: in the persistent freshness of the wound for the people left behind. "I talk about him a lot," says the friend. We are on Hampstead Heath, at the spot where Elliot's ashes were scattered; the friend points to what he says are flecks of the dust still visible in the soil. "He was such a big part of my life," he goes on. "Things will happen, you'll see things on TV or whatever, and I still think, must tell Elliot about that. When you go through this thing, you see people on the Tube or on the street having fun and laughing and chatting and you just think, haven't you heard? Haven't you heard about what happened?"