The Big Question: Can anything be done to stop young people carrying knives?

Why are we asking this now?

A Ggovernment report released this week says that carrying a knife is becoming normal among young people. The report, written by the House of Commons Home Affairs Committee, says that more teenagers are carrying knives because of fear and a lack of faith in the police to keep them safe.

Keith Vaz, the chairman of the committee, said that there were signs of an "arms race" between rival gangs of youths which is perpetuated by young people carrying knives because they believe their peers are too.

Is knife crime among young people getting worse?

First, it is important to define "knife crime". Most people equate knife crime with stabbings and murders. But the majority of knife crime involves any crime, such as a robbery or assault, where a knife is produced – it does not have to be used. This figure has remained fairly constant, with knives being used in approximately six per cent of non-fatal crime in 2007-08. In fact it has remained below eight per cent since 1995. The number of stabbings has increased slightly over the years, from 3,360 in 1996-97 to 4,786 in 2007-08; a 42 per cent increase.

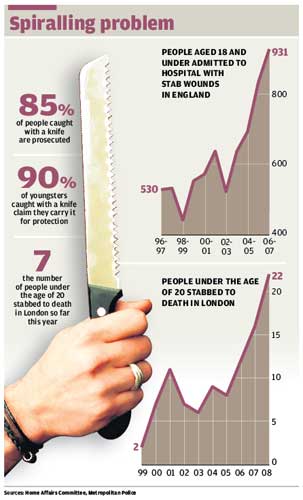

But it is the rise in the number of teenage stabbings which is most cause for concern. In the same 11-year period, the number of youngsters aged 18 and under being stabbed has increased from a low of 443 in 1998-99 to 931 in 2007-08 – a 110 per cent increase. In London last year, 22 people under the age of 20 were stabbed to death compared to two in 1999.

When did these stabbings become such a problem?

The figures seem to suggest that the numbers stayed fairly constant until 2005-06 when they started to increase sharply. But the problem came into focus last year following a spate of knife-related murders in London. Teenagers being stabbed to death became an almost weekly occurrence during the summer months.

One of the most worrying social aspects was how little those using the knives seemed to value the life of others; many of the murders appeared to be unprovoked while others were the culmination of petty feuds. Two of those killed, Shaquille Smith and David Idowu, were just 14 years old.

But was the problem blown out of proportion by the media?

There are still those who believe that the extensive media coverage of last year's stabbings was unwarranted. That the number was no more than usual and the problem was simply being overhyped by sensationalist newspapers in need of a story during the traditionally quite summer months. The Home Affairs Committee report quotes several groups who say that the media coverage actually made the problem worse. The suggestion was that young people who read about stabbings in the papers would then feel the need to arm themselves.

Yet those in charge of attempting to remedy the problem dismiss this theory, and the statistics back them up. Last year the Metropolitan Police dealt with more incidents of teenagers who had been stabbed to death than any other year in the past decade. Nationwide, more under-18s were admitted to hospital with stab wounds than any other year since 1996. Deputy Chief Constable Alf Hitchcock, the Association of Chief Police Officers' (ACPO) lead on knife crime, has said that he believes the media were reporting a real surge in the number of murders and not simply sensationalising a small increase.

Is it happening all over Britain?

Last year, Sir Paul Stephenson, then Deputy Commissioner, now Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, said that knife crime had overtaken terrorism as his force's number one priority.

The Government seemed to agree that it was a national problem and set up the Tackling Knives Action Programme. It pledged £5m to the 10 police force areas judged to be the most affected by knife crime: Essex, Greater Manchester, Lancashire, Merseyside, Metropolitan (London), Nottinghamshire, South Wales, Thames Valley, West Midlands and West Yorkshire.

The last of these areas is particularly interesting. In reaction to last year's knife crime fears, West Yorkshire Police, like many others, deployed knife arches – essentially walk-through metal detectors – at railway stations and nightclubs. In the four months the scheme ran, the force did not find one knife. A senior source explained: "The suggestion that knife crime is a national problem stems from London, where it genuinely is a problem. In West Yorkshire, knife crime is not a problem. It is not our priority. But the reason we continued to deploy knife arches is because people watch the news and think it is a problem. So seeing knife arches is a reassurance for them."

Why do young people carry knives?

The most common reasons given are that youngsters carry knives out of fear and in the mistaken belief that it will make then safer. The Home Office's 2006 Offending, Crime and Justice Survey said that 85 per cent of young people caught carrying knives claimed they did so to protect themselves. This figure has to be treated with some suspicion owing to the fact that teenagers caught carrying knives are unlikely to admit they are doing so as a means of committing crime. Also senior police officers have privately cast doubt upon this figure, suggesting that, while many young people do carry knives out of fear, a large number do so for "respect" – to make themselves appear dangerous, because they are part of gangs, or simply because they are criminals.

And why knives?

Simple. Knives are readily available from every household's kitchen. Guns are a lot harder to come by in Britain.

So what can be done to stop teenagers carrying knives?

The Metropolitan Police has already claimed some success in this area with the launch of Operation Blunt 2 last May. After just one year, serious injury from stabbings is down by 30 per cent – 221 to 155. And overall knife crime is down by 11.5 per cent (12,279 incidents compared with 13,874).

Another initiative is the use of stop-and-search tactics. Last year, 287,000 stop and searches were carried out by the Met under knife crime legislation, 10,226 arrests were made and 5,480 knives recovered. The recovery rate of stop and searches has dropped. At its highest, three per cent of stop and searches resulted in a knife being found. Now it is one per cent. This could mean that the tactic is forcing youngsters to stop carrying knives, or it could indicate that they are simply becoming wise to the locations where they are likely to be caught and are avoiding them.

But possibly the best way to put youngsters off carrying knives would be to impose a mandatory prison sentence for possession. Currently the maximum prison sentence for carrying a knife is four years. But, unlike gun possession, where the automatic sentence is five years, there is no mandatory sentence for knife possession.

There is a high possibility of being charged, however. The Metropolitan Police currently charges 90 per cent of people caught in possession of a knife.

Are we losing the battle against knife crime?

Yes...

* The number of teenagers being stabbed is at its highest level in more than a decade.

* Without a mandatory prison sentence for possession there is nothing to deter youngsters carrying knives.

* Already youngsters have learned to prevent detection by avoiding stop-and-search hotspots.

No...

* The Metropolitan Police has reported drops in knife crime and knife-related youth murders.

* Outside of the deprived urban areas of big cities, it is not as serious a problem as some people think.

* The police are charging 90 per cent of those caught in possession of a knife. This will become a deterrent.