Still lethal aged 100: UK gangs load up on antique guns - with no registration required

Experts at the National Ballistics Intelligence Service tell Cahal Milmo why Britain faces a threat from the past

Surrounded by a fearsome array of 2,000 assorted lethal weapons ranging from a rocket-propelled grenade to a homemade blunderbuss, Tony Gallagher points to a rack of 100-year-old revolvers straight out of a cowboy film. He said: “We’re seeing a few more of these on the streets now.”

As a forensic expert for the National Ballistics Intelligence Service (NABIS) at its high-security laboratory in an anonymous building in a Birmingham suburb, Tony and his colleagues know what they are talking about when it comes to weaponry in criminal hands in Britain.

The little-known agency keeps a low profile, but it is key in the fight against gun crime which has seen the number of offences involving firearms fall in England and Wales from 24,000 in 2003 to 9,555 last year.

Although gun crime remains rare (there are about 900 incidents a year in which a weapon is actually fired or brandished), it remains a grim reality, with police armed response vehicles carrying out some 13,000 operations a year. The recent inquest into the death of Mark Duggan, who was travelling with a gun when he was shot dead by police, has highlighted the persistence of the threat.

A vital tool for those officers and detectives investigating shootings is the ability to obtain rapid information about a weapon or ammunition used in a crime, including whether it has been used in previous shootings, and a national picture of just how guns are getting into the hands of criminals in what quantity, and who is supplying them.

Behind the scenes, these resources are provided by NABIS and its 40 staff, spread around three sites in London, Glasgow and Manchester as well as Birmingham.

The agency, which was set up in 2008 in the wake of anxiety at incidents such as the murders of Letisha Shakespeare and Charlene Ellis in a drive-by shooting, has become so sophisticated in identifying ammunition that it can link it to a weapon and any previous shootings within two hours of receiving forensic material. Previously the process could take up to a month.

NABIS also maintains surveillance on multiple “routes” used to acquire weaponry. One is the rise in the use of so-called “antique” pistols and revolvers, some of them dating back as far as the First World War and even the American Civil War, by criminals who are finding their paths to new weapons smuggled into Britain narrowed.

Inside a secure vault, NABIS maintains a “reference collection” of firearms held both legally and illegally in Britain, including weapons such as a 19th-century French St Etienne revolver, similar to one fired during the 2011 riots in Birmingham, or a Colt 1911 US Army pistol from the Second World War.

But whether antique or not, many of these weapons are in the same working order as the day they were made.

Martin Parker, head of forensics at NABIS, said: “The technology in these weapons has not changed for a century or more. An antique weapon can still be lethal but it is classified as a collector’s piece with no formal requirement for it to be registered.

“The problem occurs when criminals find they can’t get new weapons from outside of the country. It would be fair to say we have seen an emerging increase in the use of these antique guns.”

The trend is just one of several that is carefully monitored by NABIS.

At any one time, the agency is analysing issues from the emergence of the Turkish-made Zoraki gas gun as a favourite of illegal gunsmiths, to 3D-printed plastic guns, which currently pose as much of a risk to their users owing to their tendency to explode when fired.

David Thompson, deputy chief constable of West Midlands Police and the lead on gun crime for the Association of Chief Police Officers (ACPO), said: “The firearms issue is like constantly squeezing a balloon. You press on one part of the problem and it pops up in a different form elsewhere.

“There has been success in recent years. Our firearms legislation is extremely tough and it has certainly played a role in deterrence. Police forces have also got much better at tackling gun crime and gathering evidence. That is in no small part due to work at NABIS. But there is no room for complacency.”

One urgent priority is work by NABIS and ACPO with the Home Office to revisit the regulations surrounding “antique” guns to ensure viable handguns are prohibited or more tightly controlled.

A rise in burglaries of gun collections, including the theft this summer of 26 deactivated pistols in Suffolk, has further increased concern that old weapons are getting into the wrong hands.

It is up to NABIS, which runs on a modest budget of £1.6m, to piece together the wider picture.

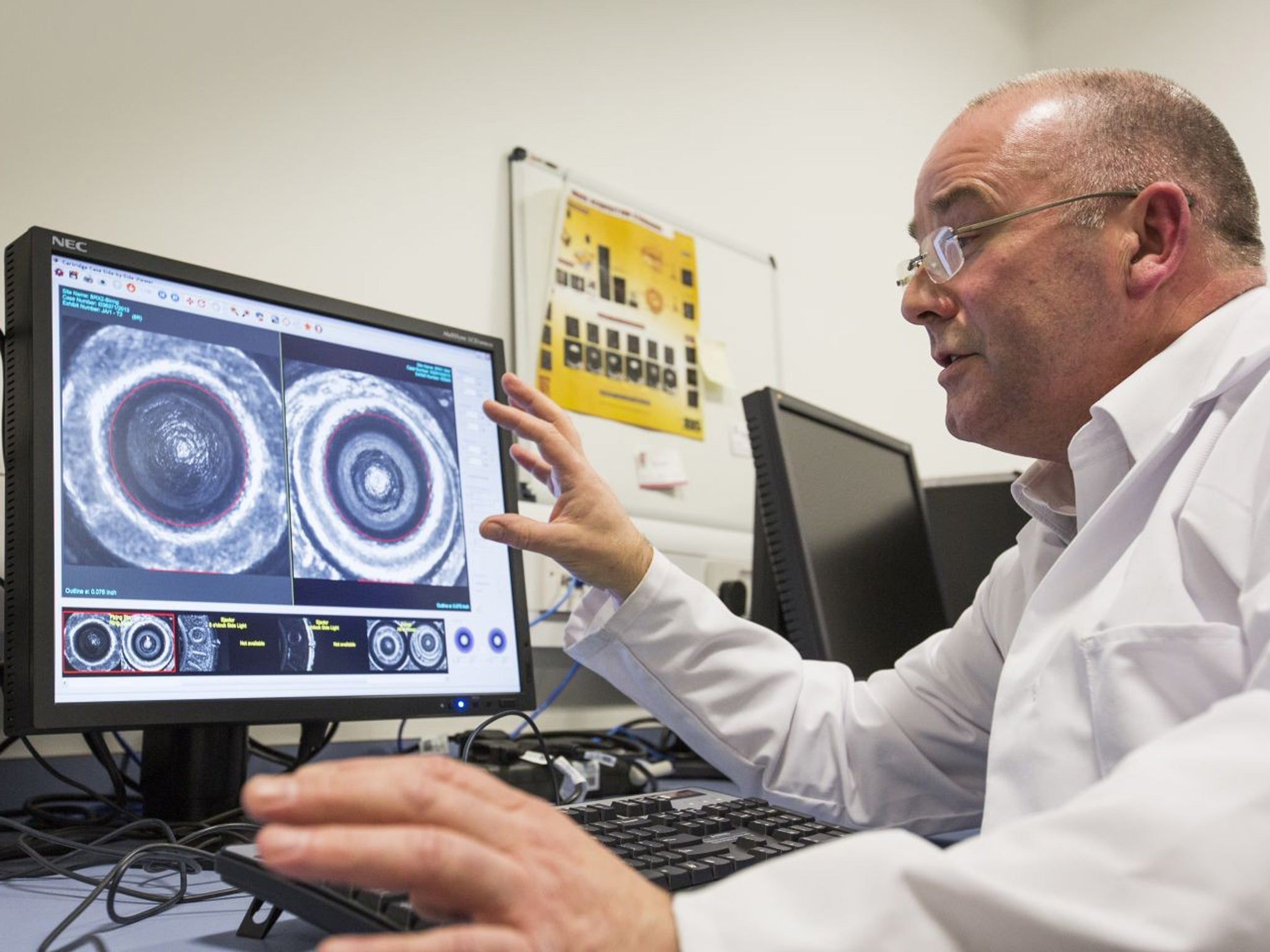

When a bullet or weapon is found by police and linked to crime, it is sent to one of the agency’s labs for analysis using tools ranging from ultra-sophisticated software to capture and magnify the markings left on ammunition to the large water tank used to a child’s seaside fishing net used to retrieve test-fire bullets from a large water tank.

In one of its more irregular cases, a testicle containing a bullet was sent to NABIS by a surgeon who had removed it from a Jamaican man shot more than 12 year earlier.

Mr Gallagher said: “It is certainly the most unusual case I’ve dealt with. The man had been shot in the back and the bullet lodged in the testicle. I think the surgeon felt it should be looked at.”

Notwithstanding the location of the bullet, the methods of identifying ammunition remain the same.

As the gun’s hammer hits the breech face of a cartridge, it leaves on the ammunition a pattern of grooves and scratches that is the unique “fingerprint” of that weapon.

Computers analyse each cartridge and bullet brought into NABIS for a match with those used in previous crimes, uniting a gun with incidents often committed years and hundreds of miles apart.

Once the match is verified by eye using a microscope it is shared in order to build up a comprehensive picture of each weapon and the network of individuals – from Lithuanian back-street gunsmiths to gangland quartermasters – surrounding it.

NABIS is reticent about putting a figure on the total number of guns held illegally. The days when a gang member might conduct a drive-by shooting with a weapon such as the “spray and pray” Mac 10 submachine gun have largely passed.

But given that some weapons can disappear for up to eight years before surfacing again at a crime scene, officers believe there is a trickle of illegal weaponry getting into Britain from abroad.

Whether that is through routes such as converted weapons or new handguns being couriered in pieces from the United States, or indeed components being made on 3D printers as the technology becomes more reliable, there is little sign of NABIS laboratories running out of work.