Stepping Hill nurse Victorino Chua: How an 'evil angel' avoided suspicions to begin a hospital killing spree

Chua’s written confession details the nurse’s darker side

To his patients and colleagues, Victorino Chua might once have seemed the caring figure they all needed: dedicated, enjoying his work, worthy of the “angel” cliché so often attached to nurses.

If the murderer’s account to one BBC journalist is to believed, his patients even “loved him” so much that one woman told him: “Vic, I want to marry you.”

It was only in January 2012, after his arrest on charges that would lead to the conviction for murder, poisoning and grievous bodily harm, that detectives found a darker, doubtless truer, account, written in the killer nurse’s own scrawled block capitals: “I’m evil at the same time angel.”

He called it his “bitter nurse confession”. Police found the sheafs of paper stuffed into a drawer at Chua’s family home in Stockport, where, it was reported, pictures of Jesus and the Virgin Mary seem to stare down from every wall.

Written in broken English and covering 13 pages, it was, Chua insisted, written in June 2010 after a counsellor suggested that he put his feelings down on paper, simply to alleviate the frustration and anger he was feeling at the time.

But to the detectives investigating him it was an insight into the mind of a narcissistic, psychotic murderer and a life that began in happiness but spiralled into petty crime, deceit and, ultimately, betrayal and killing.

Born on 30 October 1965, he was the third of six children to Angel Noblo Chua Snr, who ran a computer business, and Vuanaita Domingo.

“We live a happy life when I was a kid,” the 49-year-old father-of-two began his account. “Got all we need in the house. You name it. We have it. We are the envy of our cousins and neighbours.

“We get a nanny every one of us. They wash and drives us, cook food what each one want. I thought our well-off life will not end.”

But his parents “split up because my dad got four wives to support”. According to Chua, life turned sour. “I hated my parents because [they] left us [to] live like animals living with our relatives,” he wrote.

Chua ended up with his grandmother, who encouraged him to go into nursing, even though, he wrote, he hated it. By this time he had also acquired in high school a taste for drugs that would eventually lead to him characterising himself in his drug-taking, drug-dealing and womanising days as a Manila nurse as “evil at the same time angel”.

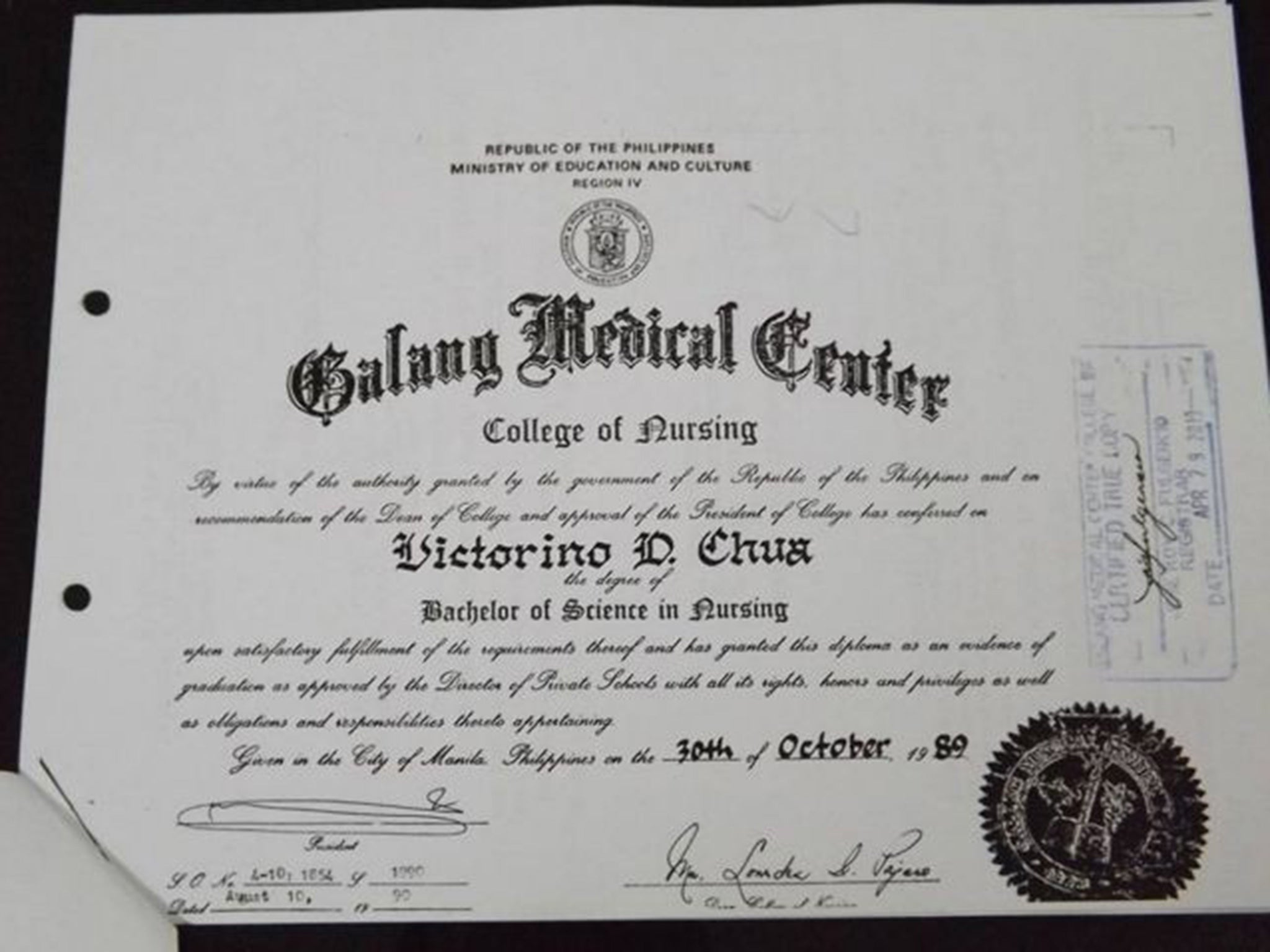

Chua began studying nursing at Manila’s Metropolitan Medical Centre, but when the fees proved too expensive, he moved to the Galang training college. Precisely what Chua achieved at this now-defunct institution is a source of no little anxiety for the British regulatory authorities.

In his “bitter confession” Chua said it was a “big surprise” when he passed his board exam allowing him to work as a casualty nurse in Manila. When British detectives examined his certificate, they found it contained a photograph of a student who didn’t look like Chua, suggesting he paid someone to take the exam for him.

Their suspicions that his qualifications were bogus were further aroused by the fact that they found three different versions of his medical school record. They also established that he left one hospital in the Philippines after being caught stealing. None of which stopped Chua working as a nurse after arriving in the UK on an initial two-year work permit. When he registered with the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) in 2003, he needed to provide only copies of his certificates – not the originals.

Today’s requirement for originals, and for an online test to be completed before the applicant can apply for a UK visa, were not in place. Stepping Hill Hospital managers would also say later that his references were vetted without any causes for concern being raised.

Chua settled in Stockport with his wife, Mary Anne, and their first daughter. A second daughter was born in 2005.

He began working in care homes. In one, in Stockport, he argued with his fellow Filipino colleagues. They would be referred to as “nasty bitch” in his “bitter confession”.

By 2010 he had suffered a series of health setbacks. He needed painkillers for back and knee pain, and was on sleeping tablets and antidepressants.

But still he thought he had deceived his colleagues and friends. “They thought I’m a nice person but there a devil in me,” he wrote. And, it seemed, the devil in him was close to winning. Writing his bitter confession, about a year before his killing spree began, he concluded with a final prophetic yet self-absolving and self-regarding passage: “Inside of me I can feel the anger that any time it will explode.”

In the summer of 2011, the first patients started to suffer unexpected hypoglycaemic attacks at Stepping Hill Hospital.