Good cop: The Becky Watts family liaison officer on a harrowing yet rewarding job

Behind the scenes of every murder case are family liaison officers who offer a lifeline to victims’ relatives

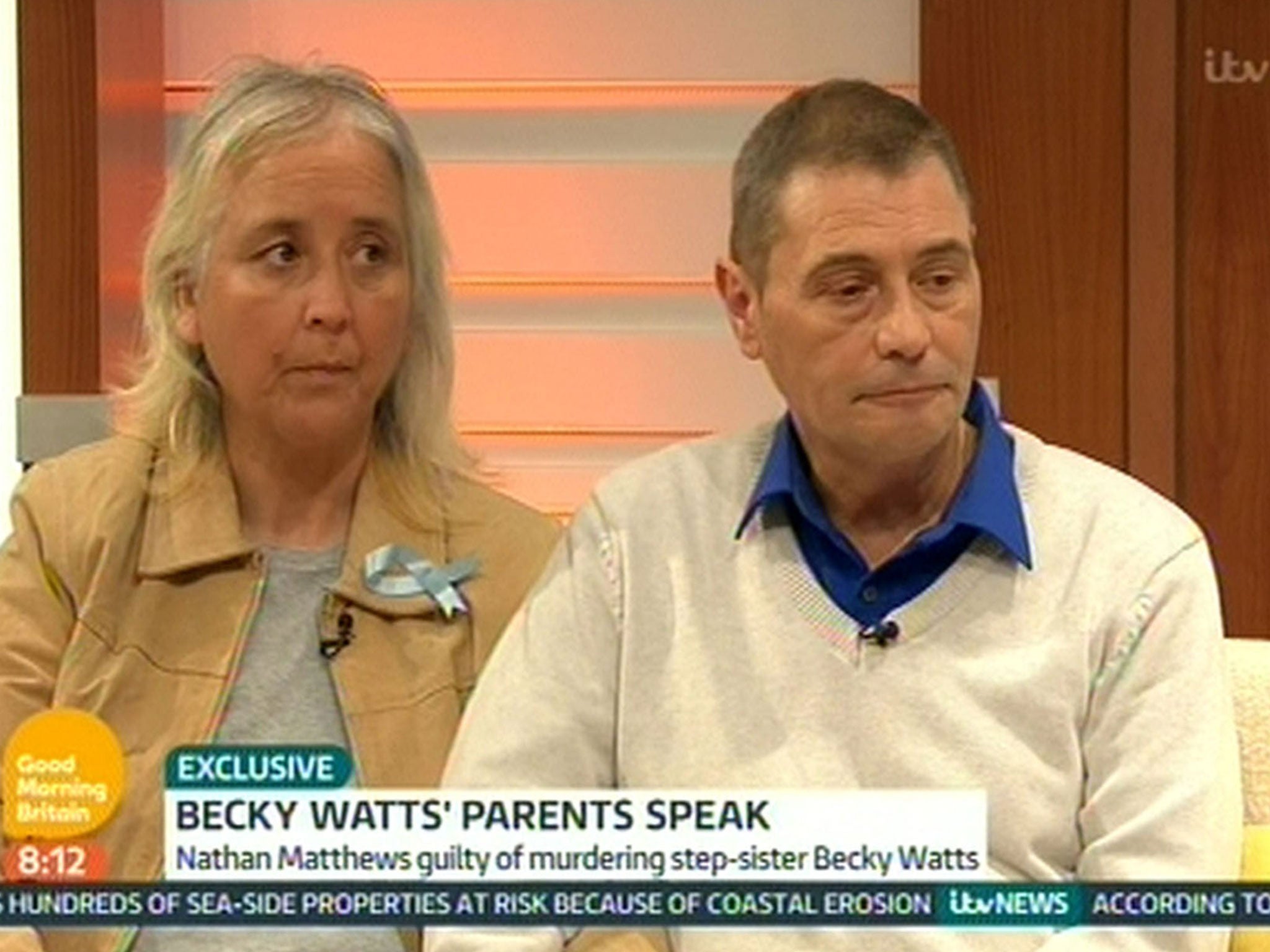

It was a measure of the horror of the case that the judge began to cry while he sentenced the murderers. Mr Justice Dingemans had just told Nathan Matthews that he would serve at least 33 years in prison for killing his stepsister, Becky Watts, and dismembering her body. Matthews’ partner, Shauna Hoare, received a 17-year sentence for manslaughter after the trial this month.

“Finally, I should like to pay public tribute to the family of Becky for the dignified way in which they have conducted themselves throughout these proceedings,” the judge, a father of teenage girls, said when his voice began to tremble. “Hearing the evidence during the trial has been difficult for anyone but it is plain that it has been an immense burden for the family.”

It had been, and on the steps of Bristol Crown Court after the guilty verdict two days earlier, Becky’s uncle, Sam Galsworthy, was quick to express the family’s gratitude to the police. He named two officers, using their first names. The women stood behind him, where they had been for several months. “We would like to thank our family liaison officers, Ziggy and Jo, who have been amazing throughout this whole process.”

Weeks later, Detective Constable Sigrid “Ziggy” Bennett is back at Avon and Somerset Police’s major crimes unit in Bristol, still reeling after the biggest case of her career, to talk about a critical, yet misunderstood, side of policing. She joins Tim Copik, a veteran detective who now coordinates the force’s team of family liaison officers, known in the trade as FLOs.

“People think family liaison is all pink and fluffy,” Copik says. “People have said to me, all you do is make the tea,” Bennett adds. “And that’s from other investigators in the team.” Copik continues: “And that’s the way it used to be – we were a shoulder to cry on, someone to put the kettle on and help take the kids to school.”

The Becky Watts investigation, known to the police as Operation Bicton, and a new documentary on Channel 4 throw new light on a specialised, pressurised form of policing. Copik and Bennett describe a role that can be as stressful and traumatic as it is rewarding – and a transformation in the past decade or more in the way police deal with the living victims of murder.

Copik features briefly In Murder Detectives, which starts tonight and continues for three consecutive days as it follows a murder case from the inside – the stabbing in Bristol last year of a teenager called Nicholas Robinson. In this case, the FLOs had the additional pressure of liaising with filmmakers. But for the force, it was worth the effort as an opportunity to show what they do.

Cases gone bad often compel the police to reform, and the Stephen Lawrence murder had a major role in changes to family liaison. The 1999 Macpherson Inquiry into the Metropolitan Police’s investigation of the 1993 murder in south-east London revealed widespread failings, not least in the way police dealt with the teenager’s family. Race was central, but so was a lack of proper training and professionalism.

The report’s recommendations included an overhaul of family liaison. Avon and Somerset Constabulary, which investigates roughly seven murders a year, was the first force in the country to formalise its FLO training 15 years ago. Copik now manages around 80 detective constables who have FLO training and voluntarily do family liaison between regular detective work.

Two FLOs are assigned to a family after a murder or when a child goes missing, which is how the Watts case started when the 16-year-old disappeared last February. (FLOs are also dispatched as part of international responses to disasters or terror attacks abroad.) For the past five years they have also been able to work with a caseworker from the National Homicide Service, part of the Victim Support charity. They take on much of the support, dealing with anything from probate to employers, or finding the right counselling. “They do all the things we used to do our best to pick at,” Copik says. “Families now get a much better and more joined-up service.”

Bennett joined the Watts investigation as a detective and interviewed Shauna Hoare. When a colleague retired, she switched to a liaison role with the Galsworthys, the family of Becky’s father, Darren (he and Becky’s mother, Tania Watts, were separated. Darren’s current partner is the mother of Nathan Matthews). Arriving with deep knowledge of the case increased the biggest challenge for a FLO – balancing a family’s natural appetite for information with the need to progress and protect the investigation. If that balance is tipped, trust or even the future trial can be jeopardised.

“There was a lot of evidence we couldn’t go through with the family, including the way Becky was murdered,” Bennett says. “They didn’t know that until the day it was due to come out in evidence. That was tricky because you want to know. Darren had been imagining even worse ways and when we told him how it had happened, he said he’d wished he’d known sooner.”

FLOs make it clear they are detectives, not counsellors, and will feed everything into the investigation while assisting senior officers in every aspect of the case. But they must also be trusted figures who can give a family representation when their feelings and concerns might have been neglected. As a result, they can also become sitting ducks for frustration or anger. “A lot of families have never dealt with the police or the law before,” Copik says. “You also have to be non-judgemental,” Bennett says. “I always put myself in the family’s shoes... what would I expect from the police?”

Old and new media can be useful in a missing-person case, but also a distraction and threat. “We just can’t keep up with social media,” Bennett says. “When Becky was still missing the family would ring us and ask why they hadn’t been told about something that had been found. If we told them every time we’d discovered a bit of discarded clothing not related to the incident, we’d be ringing them every hour.”

Then come the hungry reporters bearing big cheques. The choice to sign a deal is the family’s, but “sometimes the drive to do your job as a journalist blinkers you from the misery people are suffering”, Copik says. “It’s a fine line. Something that seems so innocuous it wouldn’t cause anyone to flinch can, with the strain of grief, send someone over the top and FLOs are the ones who can take the brunt of it.”

Families can also turn on each other as well as the police, and FLOs can witness fracturing relationships or mental breakdowns – or even suicides. Children may suffer the most. Sometimes, family members can become suspects during an investigation. The hours can also be punishing and FLOs are offered counselling.

The goal is to reach a trial and justice. For six weeks in Bristol, Bennett and her colleague sat with the family through every minute of a harrowing trial, briefing them before each day and taking them home to discuss what had happened, before returning home to their own families. Then came the verdict. “I took a deep breath and a deep swallow because above all it was the result the family needed.” Bennett says. “They can now move on to the next step and grieve.”

‘Murder Detective’ starts on 30 NOvember on Channel 4