‘Paedophile hunters’ do not violate right to privacy, Supreme Court rules as convict's appeal dismissed

‘The interests of children have priority over any interest a paedophile could have in being allowed to engage in criminal conduct’

“Paedophile hunters” do not violate the right to privacy, the Supreme Court has ruled while dismissing a convict’s appeal.

Mark Sutherland was convicted after communicating with a member of an activist group, who he believed to be a 13-year-old boy.

He appealed his conviction, arguing that his right to a private life and correspondence, enshrined in Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR).

Delivering the Supreme Court’s ruling on Wednesday, Lord Sales said the appeal had been “unanimously dismissed”.

“There was no interference with the accused’s rights under Article 8,” he added.

Lord Sales said Sutherland believed he was communicating with a 13-year-old boy, and had no “reasonable expectation of privacy” because a child could tell an adult.

He added that authorities have a “special responsibility to protect children against sexual exploitation by adults” and that overrides the right to privacy for such “reprehensible” communications.

“The interests of children have priority over any interest a paedophile could have in being allowed to engage in criminal conduct,” the judgment added.

The court heard that Sutherland was convicted of attempting to communicate indecently with an older child, and related offences, in August 2018.

A group called Groom Resisters Scotland had set up a fake profile on the dating app Grindr, which he engaged with.

After they “matched”, the person claimed to be a 13-year-old boy and Sutherland sent sexual messages and images.

They arranged to meet at Glasgow’s Partick railway station, where the paedophile hunters filmed the encounter and broadcast it on social media.

The group detained Sutherland, called the police and handed over its evidence, including IIS communications with their roleplayer.

The group’s evidence was relied upon in Sutherland’s prosecution, and a trial judge dismissed his attempts to have it ruled inadmissible.

Sutherland appealed against his conviction to Scotland’s High Court of Justiciary, which granted the appellant permission to appeal to the UK Supreme Court.

At a hearing in June, Gordon Jackson QC, representing Sutherland, told the court a “huge number” of cases were being prosecuted on the basis of information from “paedophile hunters”.

“The police are aware that there are a number of hunter organisations operating in Scotland and the UK and evidence submitted from these organisations has led to a number of criminal investigations and convictions,” he added.

Mr Jackson accused police and prosecutors of giving “tacit encouragement” to such groups to continue their activities.

Opposing the appeal, a barrister for Scotland’s Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service, argued that the criminal prosecution of sexual conduct between an adult and a child ”does not engage“ someone’s rights to privacy.

“There is no right to respect for such behaviour in a democratic society,” said solicitor general Alison Di Rollo QC.

She added that it was clear that the “overriding duty” of the police was “to respond to any report of any identified person who may pose a sexual risk to children”.

The Supreme Court ruled that Sutherland had committed criminal offences by sending the messages, and said he also urged the decoy to delete them and then move to encrypted WhatsApp messages.

“The decoy was entitled to provide evidence to the police,” the judgment added.

“The appellant had no legitimate interest under the scheme of the ECHR to prevent the respondent from making use of that evidence in criminal proceedings against him.”

The Supreme Court said the evidence indicated that Sutherland “represented a risk” to children, and police and prosecutors were duty-bound to act.

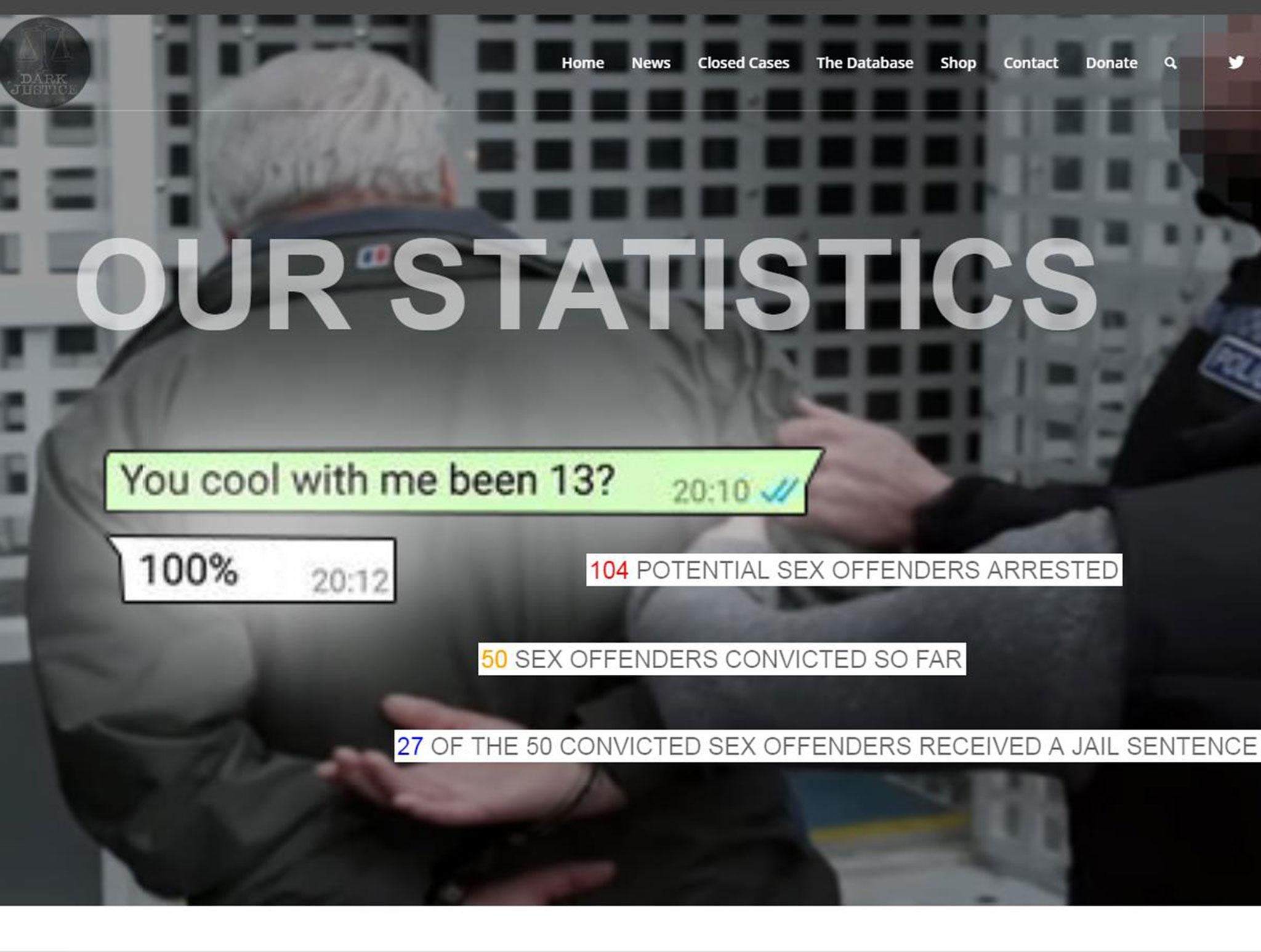

Around 90 named “paedophile hunter” groups are thought to be active in the UK, carrying out more than 100 undercover sting operations a month.

The activity is not against the law in itself but has occasionally resulted in alleged assaults, while some people targeted have taken their own lives.

Last year, six members of the Predator Exposure group were cleared by a jury at Leeds Crown Court of charges including false imprisonment and common assault after prosecutors said they “overstepped the mark” when they confronted two men.

In 2017, David Baker, 43, took his own life days after he was confronted by the Southampton Trap group after allegedly arranging to meet a 14-year-old child in a supermarket car park.

The coroner at his inquest ruled that social media posts by the vigilante group were a “causative factor” in his suicide.

London-based criminals have used paedophile hunter-style stings to blackmail people, marching them to ATMs to extort money, and in some cases child abusers have claimed to be activists when caught with indecent images.

In June Assistant Chief Constable Dan Vajzovic, the National Police Chiefs’ Council (NPCC) lead for online child sex exploitation activist groups, said police would continue to investigate their material.

”Activist groups can produce some positive results but our overall assessment is they are more harmful than they are good,” he added.

“If they carry out activities and pass us material we will investigate and we encourage them to pass material to us at as early a stage as possible.”

Last year, the NPCC’s head of child protection accused groups of being driven by “seeking infamy through the number of hits they get, the number of likes they get, the number of people that view their livestreams”.

Chief constable Simon Bailey added: “I can’t deny they’ve led to convictions, but they’ve also led to people being blackmailed, people being subject of grievous bodily harm the wrong people being accused, people committing suicide as a result of interventions, family lives being completely destroyed, in the name of what? Facebook likes.”

In 2017, he had said forces would “potentially have to look at” working with networks of paedophile hunters.