‘Killing addiction’: Criminologists on why ‘nice’ nurse Lucy Letby became baby murderer

Horrified families left asking what drove Letby to commit her appalling crimes as 33 year-old jailed for the rest of her life, Tara Cobham writes

“It can’t be Lucy - not nice Lucy.”

These were the now-chilling words of a doctor faced with yet another devasting and inexplicable death of a baby on the neonatal unit of the Countess of Chester Hospital.

But despite her “beige” appearance, it was Lucy Letby behind that and other deaths - a “cruel and calculating” killer of children, hiding in plain sight.

Now convicted of murdering seven infants and attempting to kill six others, Letby has become the most prolific child serial killer in modern British history.

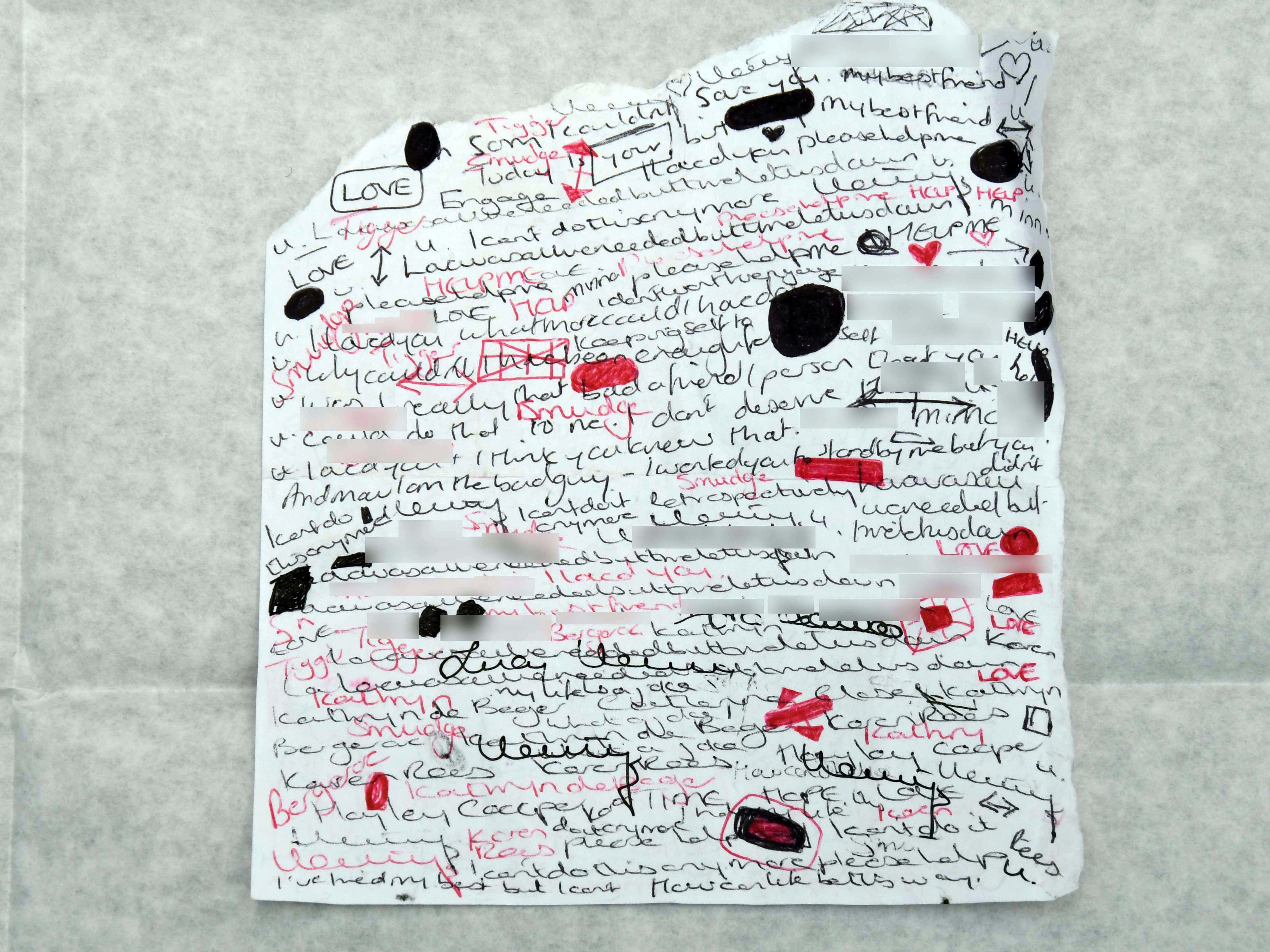

But despite being sentenced on Monday to a whole life order, questions linger about what led the 33 year-old to commit such appalling crimes. While her reasons may never be fully understood, prosecutors and other experts told jurors during her trial of several possible motivations.

Criminal psychologists have now given their own verdicts, describing the case as “extremely rare and unusual” and arguing that Letby “broke all the rules” normally applied to serial killers.

Professor Mike Berry, of Liverpool's John Moores University, has interviewed countless killers over his decades spent as a Clinical Forensic Psychologist.

“Most murders are done for sex, anger, money, hatred, revenge,” he told The Independent. “So killing babies is a very rare phenomenon, because they’re harmless, there’s no hatred involved - people can’t get their head around it. And killing babies is extremely rare among nurses, as most are sadly likely to be killed by their parents or parents’ partners.”

Another “very unusual” element of Letby’s case is her use of different methods, deliberately injecting newborns with air, force-feeding others milk and poisoning some with insulin.

“Most serial killers adopt a certain signature or modus operandi and then improve it,” he said. “I don’t know whether she was experimenting to see if different methods were possible, or if this was just a freak phenomenon.”

What he is certain about is that Letby managed to get away with the murders for so long because of the “nice Lucy” persona she had created.

“People seemed to like her and that obviously worked to her advantage,” he said. “It was so hard for people to think of her as being a killer. Serial killers are often loners. Until this happened she was a normal person. She’s breaking all the rules.”

Letby committed her crimes “quietly”, Prof Berry explained. “She wasn’t playing the heroine. She didn’t go out to provoke any attention, which is interesting.

“Some killers enjoy killing, playing God, getting a kick out of being the ultimate God. She causes harm and gets pleasure and a buzz out of causing the pain.”

Even once she was arrested and her case went to trial, Letby pleaded her innocence throughout. This also meant there was no mental health defence.

Prof Berry added that there was no suggestion she was trying to relieve her victims’ pain, which ruled out the ‘angel of death’ trope - murderers who are often medical practitioners and try to portray their actions as merciful.

For Letby, it was about the control and power of having a life in her hands, Prof Berry said.

“Killing someone does make you God - having someone’s life in your hands is a powerful thing,” he said. “It’s power and control, which leads to that buzz and pleasure. Killing is exciting for her.

“The joy doesn’t last forever - it’s an addiction. And the killing is not quite perfect, she wants to improve it, so she does it again and again.”

Professor David Canter, a forensic psychologist who helped police in the 1985 Railway Rapist case, also believes a quest for power and significance would have been the key factor influencing Letby.

In a move that he suggested could hint at her motive, Letby refused to attend her sentencing hearing, a decision that enraged victims’ families and the wider public alike.

“Surely this was a way of keeping control over her involvement,” Prof Canter said. “So the feeling of power given by killing babies may be part of the process.”

But since she never admitted her crimes, he, like Prof Berry, thought a desire for significance in the eyes of others was an unlikely motive.

Instead, he suggested her getting away with it for so long could have led to feelings of excitement or power. The contact that Letby sought to have with the parents could similarly have led to a feeling of power, he said, in “enjoying their deep distress”.

Prof Canter cautioned against the idea of looking for a single motive, but suggested that looking at Letby’s first victim was the “key to understanding her”.

“What were her earlier activities that paved the way for this? Did that happen by accident? Was there some trigger at that point, or special circumstances that caused her to kill?

“Once she got started, it almost became a habit.”

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks