Is Lucy Letby a psychopath – and would she have killed if not?

As Letby’s lawyers claim an expert witness at the trial, Dr Dewi Evans, has changed his mind on key evidence, a new book has been released that explores how a nurse could go from an ordinary young woman to the most prolific child killer of the modern era. Here authors Jonathan Coffey and Judith Moritz reveal what they discovered about her state of mind...

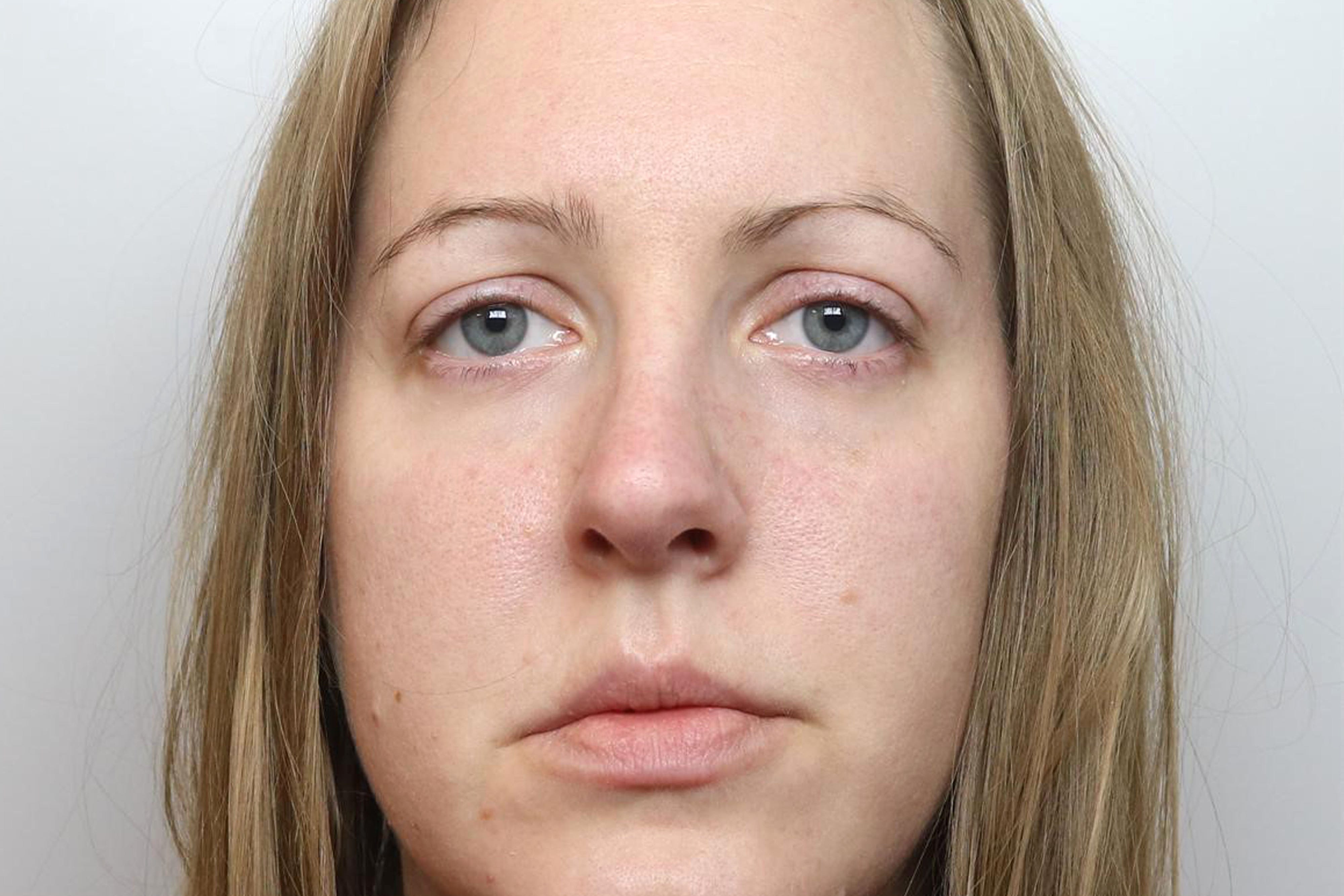

Lucy Letby is Britain’s most prolific child killer of the modern era. Surely someone fitting that bill must be a psychopath. After all, what other name would you give to someone who has murdered seven babies?

During the research for our book, we spoke to a consultant forensic psychiatrist who has assessed and treated mentally disordered offenders in the North of England, including several who have been convicted of murder and manslaughter. Dr Michael Crawford hasn’t been involved in the Lucy Letby case, and without being able to assess her in person he is unable to make a clinical diagnosis.

However, like anybody else, Dr Crawford has been able to look at the information in the public domain, including Letby’s text messages and other material from the trial. There’s a common assumption that serial killers are psychopaths – manipulative, lacking in empathy, and with no regard for the consequences of their actions.

But Dr Crawford believes that doesn’t ring true here: “She doesn’t seem psychopathic to me. She appears more like an inadequate woman who’s living a very empty life that has this real need for fulfilment.”

Professor Mark Freestone agrees that Letby doesn’t display symptoms of psychopathy. An expert on forensic mental health, he’s worked in prisons and the NHS with some of the UK’s most notorious and high-risk criminals. He points out that psychopathy is not as well understood in women as it is in men but says the associated antisocial behaviours “are things that just don’t occur in women with anything like the same kind of frequency”.

He says, “Psychopaths are inherently quite chaotic. They don’t do ‘normal’. They don’t make bedrooms look nice so they can live there. Everything is temporary, they’re usually quite promiscuous sexually. They’re pathological liars who don’t lie constructively. There’s pretty good evidence that there is a neurological problem in people with a diagnostic psychopathy ... I just don’t get any of that from Letby at all.”

Not all psychopaths are criminals, and not all serial killers are psychopaths. But if psychopathy isn’t at play, mustn’t there be another psychiatric explanation for serial murder? Not always. It’s hard to get much further without considering another famous case involving a medical serial killer.

Harold Shipman is the most prolific British serial killer of our times – murdering hundreds of his patients. Dame Janet Smith, who chaired the government-commissioned Shipman Inquiry, produced six reports into the doctor’s crimes. She asked four forensic psychiatrists to offer their opinions and advice on his likely state of mind. Unable to examine him in person, they made their assessments based on documentary evidence, including his medical and prison records. Dame Janet reported that “They did their best to consider possible explanations for Shipman’s conduct but, with the materials available, were unable to reach any conclusions.”

The Lucy Letby case seems to take us to much the same place: multiple convictions for heinous crimes and no obvious psychiatric theory to explain them. And yet, that doesn’t mean there isn’t such an explanation.

Borderline personality disorder, or BPD, is another theory that’s been floated to make sense of Letby’s mental condition. BPD is a disorder of mood and how a person interacts with others. Emotionless reactions are one red flag for the condition. This does chime with what we witnessed of Letby in court over the course of both trials. Her demeanour was studiedly blank. Her frumpy clothes in muted colours, drab hair and blank expression all seemed designed to deflect interest and say nothing.

Julia Quenzler and Elizabeth Cook each have more than 30 years’ of experience drawing some of the most famous trials – and infamous defendants – in British legal history. Quenzler remembers that Beverley Allitt had been animated, chatting with the dock officers, and Shipman folded his arms in arrogant defiance. Letby’s body language was entirely different: “She just looked somewhat vacant and sat very still. It was difficult to read anything from her – I don’t recall seeing anyone quite like that before. You’d almost have thought that perhaps she was on some sort of medication – I didn’t see any reaction, movement or any expression.”

She remarks, “The only other person who was like that was [serial killer] Rosemary West. She sat expressionless and still the whole time too. Very similar.”

Some people will legitimately point out that a courtroom is the last place that someone’s true personality and feelings will be shown – particularly someone with a tendency to be reserved when outside of her comfort zone. They may also point out that by the time of her trial, Letby had been in custody for two years. Her world had imploded. What is “normal” behaviour for someone like that?

It’s also worth remembering that Letby wasn’t completely emotionless during her trial. She did crack, albeit only a handful of times. There was the moment she burst into tears on hearing the married doctor give his name, and there were occasions when she was in the witness box, and the questioning hit a nerve. Her barrister, Ben Myers, wanted to get her to express her feelings, and she broke down momentarily, telling the court that she was devastated and had only ever done her best, and her face crumpled.

We put it to one of Letby’s old friends that she looked blank and poker-stiff in court. “She was clearly petrified!” they told us. But with the exception of a few memorable moments, she was devoid of emotion – incomprehensibly so. So could the borderline personality theory be right? Could this fit with Letby as a serial killer?

Letby’s performance in court isn’t the only basis for entertaining such a theory. On the ward, this came across as businesslike and efficient – or as she once described herself to her doctor crush, “serious Lucy”. She was often shown to have misjudged the mood around vulnerable families – or at least seemed to put her own needs ahead of theirs – hovering around the parents of Baby D as they willed her to give them some privacy, and upsetting the parents of Baby I by chattering brightly at them while they bathed the body of their dead daughter.

She was also noted to be particularly calm during resuscitations. More than one colleague observed that she was almost too calm – unnervingly so, as if she was in her comfort zone.

It was this behaviour which alarmed consultant Steve Brearey when he observed Letby after the two triplets had died in June 2016, and saw that – while other staff were in pieces – she seemed to be unaffected. Her breezy refusal of his offer to take time off, and her determination to work through the weekend, struck him as totally different to the way the rest of the team had responded to the two deaths.

The detectives who arrested Letby say they observed something similar when they got her back to the police station for questioning. Paul Hughes, now a detective superintendent, was the senior investigating officer in charge of the police probe.

He remembers: “She was very emotionless. She didn’t respond in a typical human way that I would have expected. We didn’t see any sadness, or any passion, or anything more – like an innocent person banging on the table demanding that we should go and find the proper killer. There was nothing from her that appeared to be affected by what was going on around her.”

Prosecutor Nick Johnson KC latched on to the same point in court when he started his cross-examination of the nurse by asking her why she only cried when talking about herself, and not when mentioning the babies. Letby denied it, but the barrister was only voicing a question that we’d all been wondering for weeks ourselves, having witnessed it first hand.

But as with almost everything in the Letby case, there is an alternative way of looking at the evidence. One of Letby’s former classmates had told us Letby could appear “stony and cold”. Letby’s old friend Dawn said something similar: “Outside of our group she would present as shy, reserved, serious, you know, level-headed.”

According to Dawn, that was just Letby’s nature. Nothing serious or sinister. If Dawn is right, it is perhaps to be expected that Letby would be quiet or awkward around senior consultants and at her most reserved and introverted in a courtroom.

We also know that Letby did become emotional around people she trusted. After she was removed from her position on the neonatal unit in July 2016, the lead nurse for urgent care Karen Rees became one of Letby’s most trusted confidantes. She later said: “I witnessed her in complete distress, crying and swearing her innocence.”

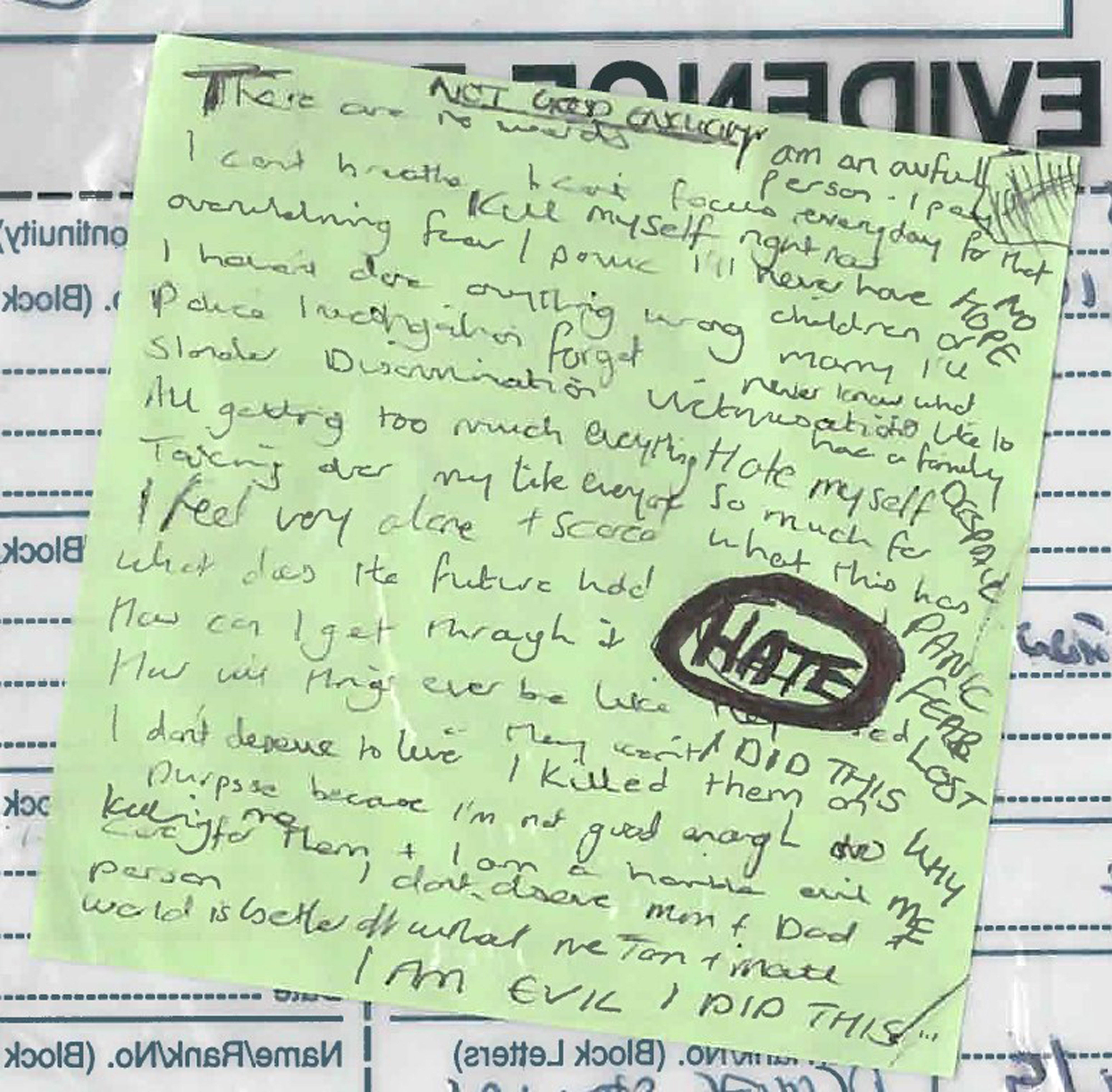

Debates over whether Letby’s emotional responses are suggestive of borderline personality disorder have no easy resolution. The question that we really want an answer to is this: given what we know about Letby, can we find a possible motive or “reason” for her to murder babies? The difficulty of this question was captured powerfully by the mother of babies E and F: “She had everything going for her and then starts killing babies. What happened?”

Unmasking Lucy Letby by Jonathan Coffey & Judith Moritz is published in hardback, eBook and audiobook by Seven Dials, out today

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks