Prison unit holding Britain’s most dangerous terrorists closed four days after London Bridge attack

Author of government review into extremism in prisons calls system ‘dysfunctional and naive’

A prison unit for Britain’s most dangerous terrorists was closed four days after the London Bridge attack, sparking accusations the prison service is “dysfunctional and naive”.

The separation centre at HMP Woodhill is one of three set up to hold Islamists who are feared to be radicalising other inmates, but it has been empty since last Tuesday after three prisoners were moved out.

The Ministry of Justice insisted the closure was temporary and said the capacity was not currently needed, but a former prison governor who led a review of Islamist extremism in British jails said the centre had not been used properly.

Ian Acheson told The Independent that prison staff were unable to get dangerous inmates transferred into separation centres because of “extraordinary bureaucracy”.

“I’m afraid the order and control crisis in many of our prisons probably masks and obscures some of the developing threat,” he added.

Mr Acheson said the closure at HMP Woodhill was “absolutely not a surprise to me knowing how dysfunctional the organisation is”.

He added: “They’ve dragged their heels, then not tried very hard. Separation centres have never been used to their full potential.”

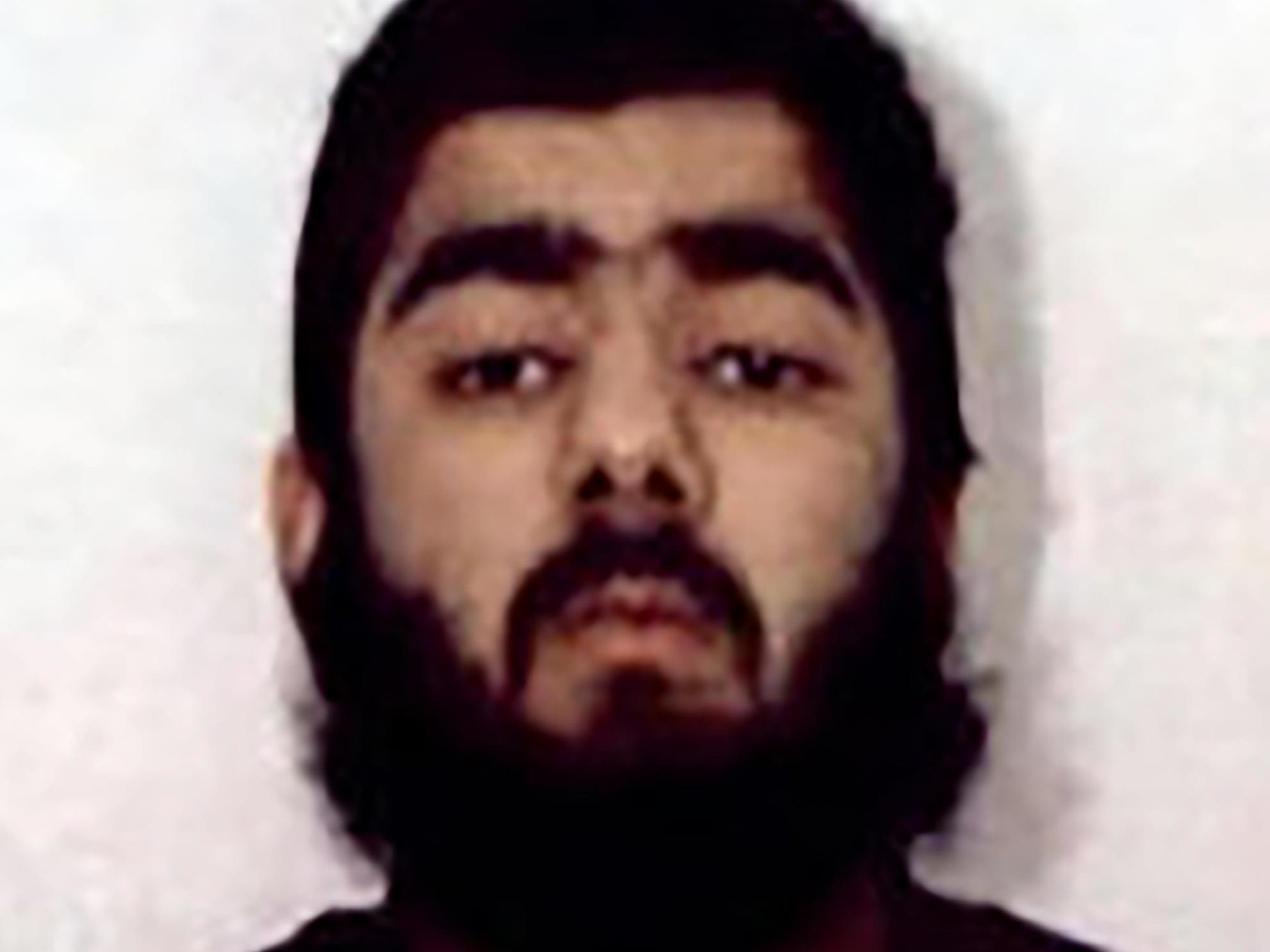

Usman Khan, who killed two people in a knife attack at Fishmongers’ Hall on 29 November, is not believed to have been held in one of the centres.

Officials have insisted that he took part in deradicalisation programmes during his jail sentence for plotting al-Qaeda-inspired bombings on targets including the London Stock Exchange.

But his attack, which took place at a prison rehabilitation event linked to Cambridge University, has raised questions over the accuracy of risk assessments both inside jail and after release.

Mr Acheson said that during his 2016 review he was told of terrorist offenders “gaming” a deradicalisation course.

“They knew what to say and do to pass the programme,” he added. “There are levels of naivety here ... it’s one thing to say they ticked every box, have they ever considered false compliance?”

The licence conditions of freed terror offenders are being reviewed, and there are calls for MI5 to update the system used for predicting whether extremists will launch lone attacks.

There are 224 terrorist prisoners remaining in custody, with 77 per cent categorised as Islamists and 17 per cent extreme right-wing.

But only a handful are kept in the three separation centres, prompting concerns that staff are not spotting dangerous behaviour, or that the process for referrals is too difficult.

A study published by the Ministry of Justice in July found the “process for referral was not as straightforward as it could be” and that some staff members flagging extremists did not understand why their requests had been removed.

The document, which was based on interviews with staff, said they may have been “discouraged” from moving prisoners into separation centres by legal action by some inmates, amid hundreds of complaints over conditions in the units.

The units had been nicknamed “Guantanamo Bay” and “Muslim centres”, the report said, because only Islamist extremists had been held there despite an increase in neo-Nazi terrorist prisoners.

The report noted that fewer terrorists had been transferred than expected, and some staff feared that “prisoners had modified their behaviour” in order to avoid the move.

“It may be that these individuals are still engaging in extremist/problematic behaviour but may be doing so more covertly, so avoiding detection,” it warned.

“Others thought [low referrals] were because of low recording of extremism behaviours, especially as these did not always present the most immediate safety problems when staff were also dealing with issues such as consumption and trading of drugs, bullying and self-harm.”

Last year, a prison officer working in the high security estate told The Independent he believed at least 7,000 prison inmates in Britain were Islamist extremists.

“The extremists have their own foot soldiers radicalising people who are in for minor offences,” he added. “You’ve got someone who is in for five or six years, an ordinary criminal, and all of a sudden they are radicalised into hating anything about the west.”

He said staff were too overstretched to properly look for signs of radicalisation, and that “nobody comes in to check” whether deradicalisation efforts are being properly carried out.

The Ministry of Justice report said that many prisoners sent into separation centres refused to engage with deradicalisation programmes and psychologists, and that staff were unclear on how they would be judged safe to move back into normal prisons.

It also questioned whether housing the most influential prisoners together could risk “further entrenching or increasing extremist views”.

The creation of separation centres was one of the recommendations made by Mr Acheson’s review of Islamist extremism in prisons, which was commissioned by David Cameron in 2015.

It found that Islamist extremism was growing inside British jails, and that the growing number of terror offenders being jailed could worsen it further.

Mr Acheson said he was not consulted about how his report was implemented, adding: “Am I confident that this issue has been addressed? In a word, no.”

“It’s a completely unacceptable situation that has to be transformed,” he added.

“We owe an obligation to completely review the quality of risk management in the prison service, because we don’t want any more of these tragedies to happen.”

The first separation centre opened in July 2017 at HMP Frankland, near Durham, followed by Yorkshire’s HMP Full Sutton and then HMP Woodhill, in Milton Keynes.

The government said the three centres combined can hold up to 28 “of the most subversive offenders”.

A Prison Service spokesperson said: “We take the threat posed by terrorist offenders very seriously which is why we designed separation centres to hold the most subversive extremist prisoners and safeguard the vulnerable from their malicious ideology.

“There are a range of psychological, theological and educational activities aimed at rehabilitating terrorist offenders in the mainstream prison population and putting more of them in separation centres would undermine that work.”

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks