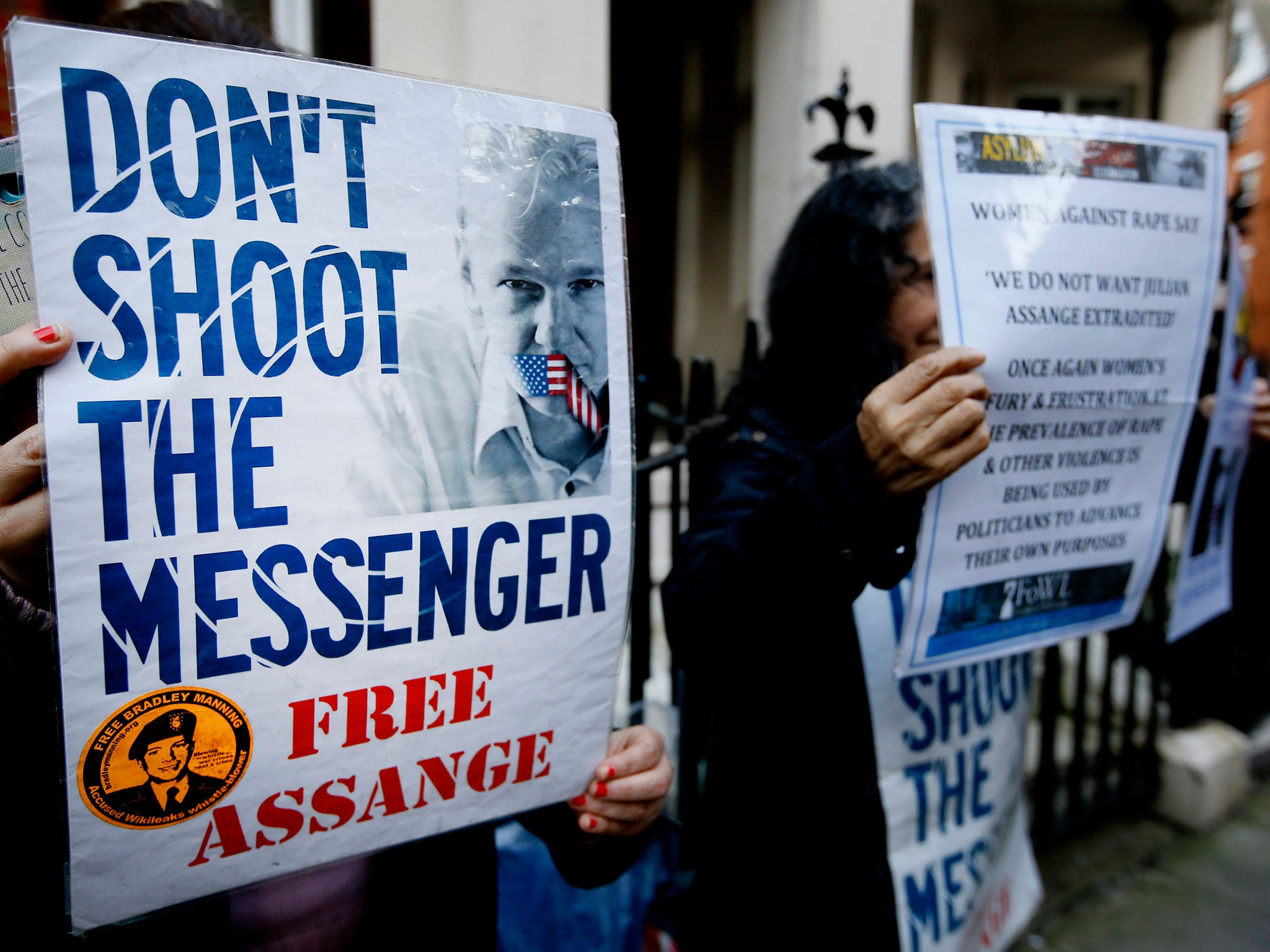

Julian Assange: Anti-rape activists say UN ruling in favour of Wikileaks founder is ‘irrelevant’

UN panel finds Assange's stay in Ecuadorian embassy amounts to 'arbitrary detention'

Anti-rape campaigners have condemned as “irrelevant” a finding by a United Nations panel that Julian Assange’s lengthy stay in the Ecuador’s London embassy amounts to “arbitrary detention” and called on the Wikileaks founder to surrender to the legal process.

Assange, who has lived in two rooms in the diplomatic mission since seeking sanctuary in 2012, appealed to the UN’s Working Group on Arbitrary Detention (WGAD) in an attempt to break the legal deadlock over his efforts to avoid extradition to Sweden to face questioning about a claim of rape. He has consistently denied any assault.

In a move likely to rankle the Government, which has spent more than £12m on a police operation outside the embassy, the five human rights lawyers on the UN panel are expected to announce that they have found in Mr Assange’s favour by deciding he has been unlawfully detained despite voluntarily entering the building three and a half years ago.

The Wikileaks chief had argued that his confinement was unlawful because he was being asked to choose between the asylum granted to him by the Ecuadorian government and the certainty of arrest if he left the embassy.

Lawyers for Mr Assange said they were still awaiting official confirmation of the WGAD finding due for release this morning but said if confirmed the extradition proceedings issued by Sweden should be immediately revoked and Scotland Yard should announce he no longer faces arrest.

Although the UN panel’s decision is not formally binding on either the British or Swedish governments, his legal team believe it will be difficult for either to ignore and hands him a significant public relations victory. One of his British lawyers said Mr Assange may seek safe passage to Ecuador.

The Wikileaks chief, who has said he will answer questions from Swedish prosecutors put to him via Ecuadorian diplomats, believes he faces eventual extradition to America to face prosecution over the publication of thousands of US diplomatic cables and military files if he is sent to Sweden.

But campaigners said they believed Mr Assange, who faces no formal charge in Sweden, was putting himself above a lawful process after the Swedish authorities said they wanted to question him about an allegation of rape made in 2010. Further allegations of lesser sexual offences against another woman can no longer be pursued after the statute of limitations expired.

Joan Smith, chairwoman of the Mayor of London’s Violence Against Women and Girls Board, said: “The UN ruling is completely irrelevant. Mr Assange is subject to the same lawful process that the rest of us are and the Supreme Court has found the arrest warrant against him was valid.

“In my view he has been desperately seeking to avoid submitting himself to this process by claiming there is a plot against him. He should be co-operating with a lawful process.”

Lawyers for Mr Assange told the UN panel that he wished to clear his name but the Swedish prosecutor had refused “unreasonably and disproportionately” to question him in London. They also argued that British law had changed since 2012 and were the same proceedings to be brought now any extradition would be unlawful.

The Swedish foreign ministry confirmed that the Geneva-based WAGD panel, consisting of academics and lawyers who are asked to present a legal opinion on cases based on existing international human rights rules, had found Mr Assange’s confinement amounted to detention and that it was unlawful.

Downing Street declined to comment on the finding but insisted that Britain continued to have a legal obligation to put the Swedish arrest warrant into effect. A spokesman added: “[Mr Assange] has never been detained in this country, so there is no arbitrary detention. He is avoiding lawful arrest by choosing to remain in the Ecuadorian embassy.”

Scotland Yard announced last year that it was winding down its visible policing operation outside the diplomatic mission after costs reached £12.6m. The Yard confirmed on 4 February that it would still seek to arrest Mr Assange if he left the embassy.

Lawyers for the Wikileaks chief said a decision in favour of him would mean British and Swedish actions had been found to be inconsistent with the European Convention on Human Rights.

Per Samuelson, one of Assange's Swedish lawyers, said: “It is international common practice to follow those decisions.”

Q&A: Julian Assange's predicament

What is “arbitrary detention” and what is the UN panel publishing this report?

Arbitrary detention is any situation in which an individual is confined or imprisoned in a way that is unlawful and infringes their fundamental human rights.

The Geneva-based Working Group on Arbitrary Detention (WGAD) was set up in 1991 and consists of a panel of senior lawyers and academics specialising in international human rights.

Many of their previous findings of arbitrary detention involve victims of repressive regimes, including Aung San Suu Kyi in Myanmar and former Egyptian president Mohamed Morsi.

So how could it apply to Julian Assange in Britain?

Lawyers for the Wikileaks founder applied to the WGAD in 2014 arguing that the scale, duration and nature of the police operation to monitor him in the Ecuadorian embassy was depriving him of key liberties.

They argued that Mr Assange was being “pursued and pilloried” by the American government and has grounds to fear persecution, adding that he was being wrongly prevented from exercising the right to asylum granted to him by Ecuador.

Does this finding have any legal force in Britain?

The WGAD is not a court or tribunal and so its formal opinions do not come from a judicial authority. They are therefore not legally binding.

But they do represent the findings of impartial UN experts on Britain’s compliance with international law. Being called out by them is both embarrassing and makes it difficult for the UK to uses its record as leverage with repressive regimes.

What will happen next?

After nearly four years of expensive deadlock, it is unlikely either London or Stockholm will give up immediately and let Mr Assange walk free. One possibility is a compromise by which Swedish prosecutors question him via Ecuadorian diplomats and then reach a decision whether there is sufficient evidence for a charge. Another is that the Wikileaks founder takes a case to the European Court of Human Rights. In the meantime, the statute of limitations on the rape claim against Mr Assange will only expire in 2020.