Joint Enterprise: The legal doctrine which critics say has caused hundreds of miscarriages of justice

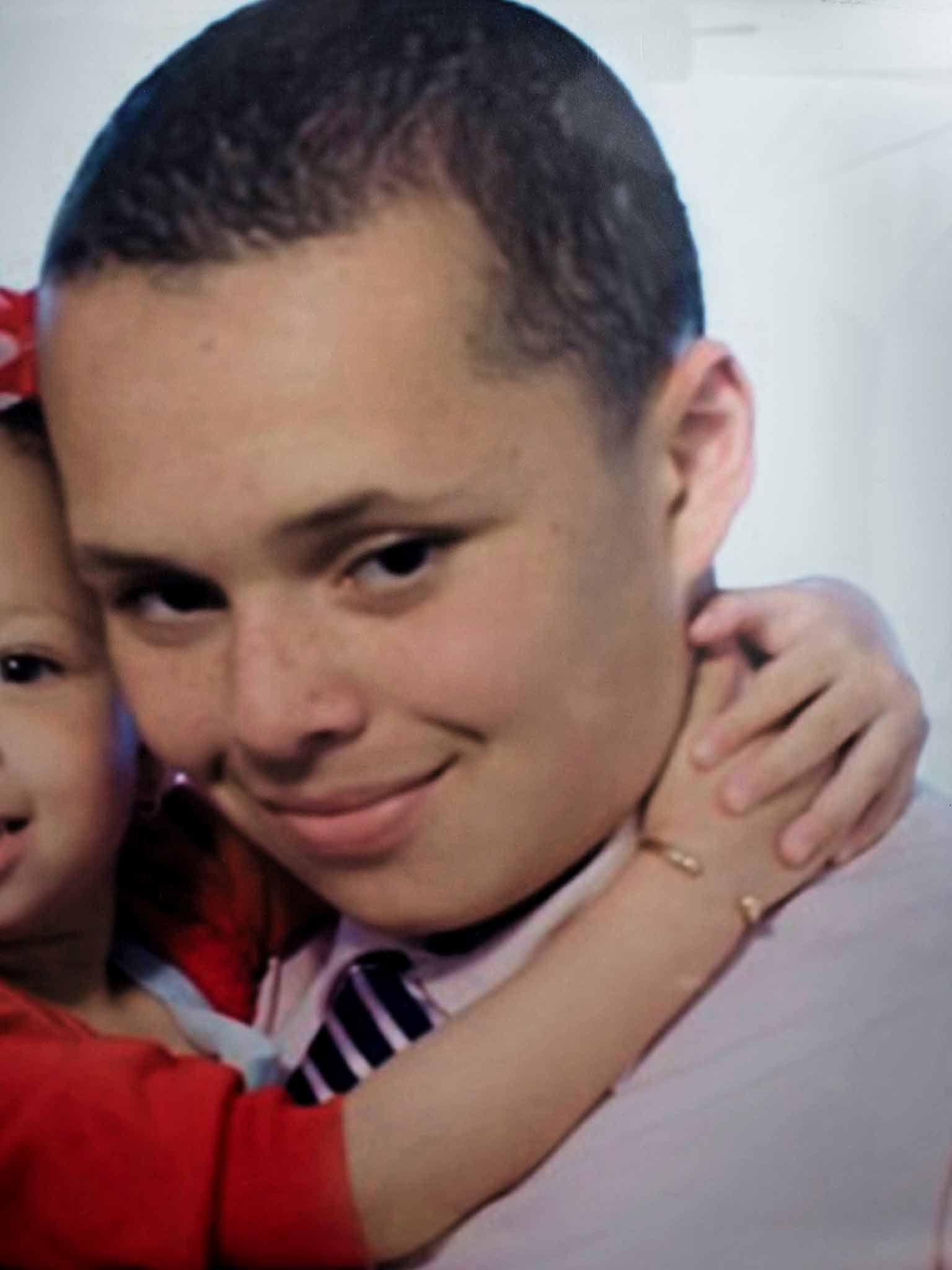

Fifteen-year-old Kyefer Dykstra is serving a life sentence for the murder of a teenager last year, but he didn't kill anyone. Lena Corner reports.

One autumn evening, a little over a year ago, 15-year-old Keyfer Dykstra was hanging around with a friend near his home in Anfield. He spotted a couple of local boys getting into an altercation with another teenager, so pedalled over on his friend's bike to see what was going on. A couple more boys followed and soon 19-year-old Sean McHugh was being pursued. The boys chased him down the notorious Cinder Path, a narrow shortcut that joins Anfield to Tuebrook, more than a mile away. No one noticed when one of them, Reece O'Shaughnessy, also 19, gave up the chase and quietly turned back.

CCTV footage picked up McHugh shortly after he sprinted into a launderette and sought refuge in a room at the back. Next, Dykstra can be seen pushing the door open and, along with three other boys, disappears behind, where a fight breaks out. Then another character appears; it's O'Shaughnessy, who had broken off the chase to go and arm himself. He crosses the launderette carrying a long, thick sword stick and disappears behind the door. He comes out again seconds later, empty-handed and quickly leaves the launderette.

Later, the court heard how O'Shaughnessy had walked in and stabbed McHugh in his left leg. The weapon made a terrible inch-wide gash in his groin and severed his femoral artery. Four days later, McHugh died in hospital. When the boys were sentenced a few weeks ago, O'Shaughnessy was given life with a minimum term of 18 years. And although Dykstra and his friends didn't actually stab McHugh, all four were also given life sentences.

The boys were convicted under the controversial legal doctrine of joint enterprise, which states that you don't have to deliver the fatal blow or inflict the lethal wound to be convicted. You can be found culpable on what is known as secondary liability on the basis that you must have foreseen that the person you were with might commit a violent act, even if you didn't actually join in.

The doctrine dates from around 300 years ago when, in an effort to deter duels, it was decreed that surgeons, accomplices and anyone else involved would be liable for prosecution, too. It's been used relatively sporadically and effectively over the years. One example in 1846 was when two cart drivers engaged in a race in which a pedestrian was knocked down and killed. Although it was not established which one had driven the fatal cart, both, by encouraging each other to race, were held jointly liable.

But campaigners are becoming concerned that in the past few years it is being used with increasing and alarming frequency in the battle against knife crime and gang culture, which has led to hundreds of wrongful convictions. They say that the doctrine is too wide, it's not applied properly and it allows a jury to convict on the most tenuous of evidence. It's been likened to fishing – slinging a large net over a crime scene and seeing what you can haul in.

"The idea that someone can foresee the actions of someone else makes a mockery of any law," says Gloria Morrison, from Joint Enterprise: Not Guilty by Association (JENGbA), a campaign group that represents those sentenced under this particular law. It launched in Liverpool in 2010 with 160 cases and the staunch support of the writer Jimmy McGovern. It is now dealing with more than 500 cases.

"The problem is that joint enterprise is largely misunderstood even among legal workers," says Suzanne King, a managing partner at SMQ Legal Services and JENGbA lawyer. "And what's heartbreaking about that is that if you go into somewhere like Feltham Young Offenders Institute, you'll see rows and rows of kids who genuinely have no idea what they're in for, let alone why they have got a sentence of 20 years just for standing around at the scene of an offence. That's the trend I'm seeing. These are kids, at the age of 15 or 16, who have had their lives turned upside down."

In 2011, amid concerns that injustices were taking place, a Justice Select Committee launched an inquiry. The report expressed concern that such a serious doctrine had no statistics and paltry guidelines. Little was done to rectify this, so in May this year a further inquiry took place. The results are due to be published tomorrow. JENGbA, is hoping that the law, in its current form, will be abolished.

Sallie Bennett-Jenkins QC, thinks that something needs to change. "There has been such a profound sense of ill ease about joint enterprise that the Select Committee may very well recommend quite far-reaching changes," she says. "Equally, it may well conclude that it's still a permissible route, but my instinct, with the mood at the moment, is that people will raise questions about it."

Bennett-Jenkins worked on the largest joint enterprise case ever – the Victoria Station murder – when 15-year-old Sofyen Belamouadden was stabbed to death on the concourse in front of rush-hour commuters in 2010. Twenty people were tried for his murder. Bennett-Jenkins was successful in securing the acquittal of one, Chris Goncalves.

"He got off because he didn't do it. He didn't have the requisite intent," says Bennett-Jenkins "He had nothing to do with the BlackBerry messaging that went on beforehand and he was not involved in any previous dust-ups between the two sectors. He was just on his way home and did what many 16-year-old boys or girls would do when a fight breaks out and that is to run over to have a look."

Dykstra wasn't quite so lucky. The Daily Mail described him as part of a "gang of sword-wielding, baby-faced murderers". He was certainly no angel. Another knife was found at the scene (although DNA evidence didn't link it to Dykstra) and he'd been in and out of trouble for a while. But in actual fact, Dykstra was on medication for severe ADHD and has a mental age of about seven. Many, many times, his mother sought help for him from social services.

"When we went to court, Keyfer was, like, "don't worry, Mum, I'll be back, I didn't do it," says Sheena Evelyn, his mother. "They were put in the dock and tried like grown men. They were just kids. One of them, when he was sentenced said, 'what does life mean, Mum?' He didn't understand any of it.

"Somebody died through all their actions and we have to remember that. He takes some responsibility, he says, 'what if I hadn't pulled that door open?' He has a lot of guilt. But what he was actually involved in was a stupid boy fight. It was a scrap that got out of hand. To give a life sentence to someone who didn't actually do it is absolutely horrendous. It was like they simply didn't need any concrete evidence to convict. As a parent, it would almost be easier to accept if he had done it."

A large part of the concern about joint enterprise centres on the fact that it unfairly targets minorities. A recent study by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism found that black British men are more than three times as likely to be serving life sentences as a result of a joint enterprise conviction than those in the prison population overall.

"The concern is that it might be working as a kind of dragnet pulling in a disproportionate numbers of young black men, and normal social relations between ethnic minority men in disadvantaged areas are, in effect, being criminalised," said Dr Ben Crewe, of the Institute of Criminology at Cambridge, when he gave evidence at the follow-up enquiry in September.

One of Suzanne King's clients, Ishmael Francis, was staggered to discover, when he appeared in court, that the prosecution had built up a carefully constructed picture of him as a fully paid-up gang member. Francis was actually a trainee youth-offender worker who rarely went out. He had just left a club with his girlfriend, where she had been celebrating her 21st birthday, when a car full of lads started hassling her. An argument broke out and when Francis saw his stepbrother leaving the club with his mates, he waved them over to come and help. Meanwhile, Francis's girlfriend went to his car and got his baseball bat out of his boot, which he claimed was there because he used it to play ball with his dog in the park. A fight ensued and one of the boys in the car was stabbed and the baseball bat was used in the affray. It was argued in court that the act of Francis waving at his stepbrother indicated common purpose.

"Francis had no affiliation with any gang whatsoever," says King. "It became very apparent that there is a big stigmatisation of gangs and gang culture. This whole case was based upon him just raising his arm. Francis's own legal team actually advised him to plead guilty to Section 18 GBH, so he sacked them and appointed us. The judge threw it out."

Janet Cunliffe, another JENGbA founder, has a son, Jordan, currently at Buckley Hall, a category C prison in Rochdale. He was with a group of boys who became involved in an altercation in the street with a man who had come out of his house and wrongly accused them of damaging his property. At the time, Jordan had keratoconus, a degenerative eye condition that left him pretty much blind.

"My son's guilt focused on the fact that he was present at the scene," says Cunliffe. "However, because he didn't see any of it, he was virtually incapable of giving evidence which sort of made him look like he was telling lies or protecting someone. He is currently in his seventh year of a 10-year sentence. He says that 80 per cent of the kids in prison with him are there because of joint enterprise and virtually all are black and Asian. He found that unbelievably shocking. I find it shocking. And that's what joint enterprise allows to happen."

Such was the concern about young people becoming caught up in these situations, London secondary schools introduced lessons aimed at teaching the meaning of joint enterprise in 2010. If you are young, inexperienced, easily led or just hanging out with people you don't know very well, there is the potential to end up in an awful lot of trouble.

And since 2006, when the starting points for tariffs for gun and knife crime were dramatically increased (now the mandatory sentence for gun crime is 30 years and 25 for stabbing), it's pretty scary stuff.

What is interesting about this debate is that it's not only campaigners and legal practitioners saying that something needs to be done. Now it's also academics who are speaking up, saying that joint enterprise has no defensible legalistic position.

"Imagine, in your daily life, if you could foresee just a small risk of something bad happening by the actions of another, if you in any way help them, even very minimally, and it does turn out they commit a crime, you are fully liable as if you, yourself had done it," says Matthew Dyson, Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge. "That is just mind-bogglingly terrifying."

Unsurprisingly, there are a lot of appeals. In 2013, 22 per cent of all cases in the Court of Appeal were for joint enterprise cases. And a steady flow continues. Emma Hall, who according to The Daily Mail is a "baby-faced leader of a vigilante gang who left her victim looking like Elephant Man", was given leave to appeal last month.

While she admits driving two men and their victim to a wasteland in Essex, when she realised that their intentions were actually to kill, she was the one who called the police. She got arrested under joint enterprise and is currently serving 15 years for murder.

It is the Stephen Lawrence case that is often cited in defence of joint enterprise. Gary Dobson and David Norris were found guilty in 2012 of Lawrence's murder without proof that either of them actually stabbed him, because evidence suggests that they were part of the small group that included the killer.

Dyson says that this view is misguided. "People say we wouldn't have got the Stephen Lawrence conviction without joint enterprise. Well, actually, in the sentencing remarks there was no mention of joint enterprise. They would both be liable under centuries-old rules on accessorial liability. But even if it was the case – and it's the only example I've ever heard attempted to be argued – it absolutely baffles me how that one case should be a reason why there are hundreds of people in prison when we have not demonstrated sufficient responsibility or culpability. I just cannot understand how one case will justify that many in prison for it."

However, Dyson is pessimistic. He doesn't think JENGbA is just about to emerge victorious. He believes that the Government has no intention of changing anything. "Aside from all the other arguments, I'm amazed we haven't taken this up on cost," says Dyson. "It costs us £45,000 per year to lock someone up. So we are talking around £1m for someone who possibly hasn't even demonstrated they have any responsibility or culpability for the crime.

"Why do we want to spend that money in a massively over-crowded system? Plus, the victim doesn't just want someone in jail. The victim wants the perpetrator in jail. Not eight or nine other people who just happened to be standing around."

JENGbA: jointenterprise.co