Joanna Parrish: There is a suspect for her murder 25 years ago - but is there a desire to bring him to justice?

Her death made front-page news, but that was a quarter of a century ago - Margaret Thatcher was still Prime Minister

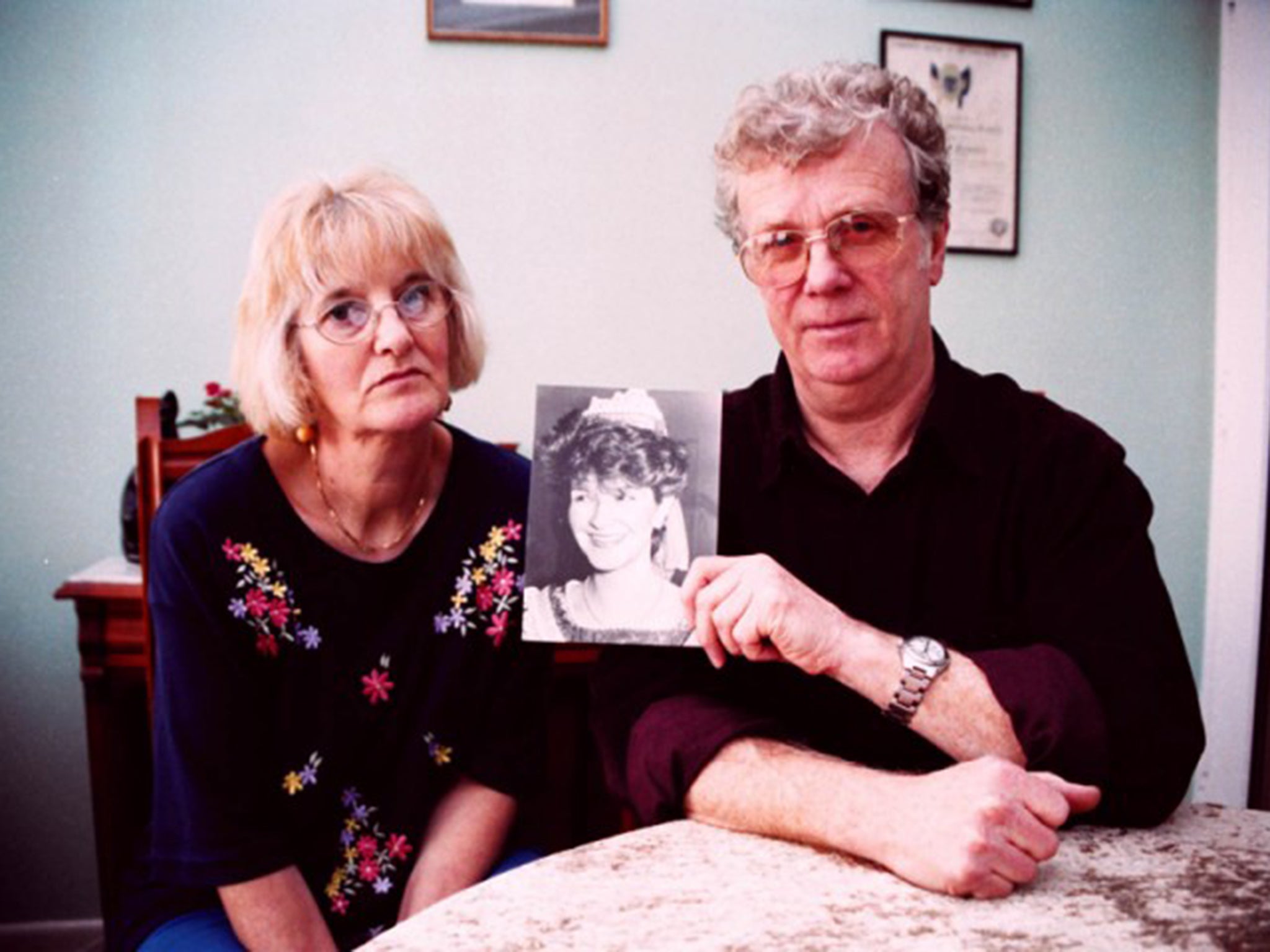

Grief stiffens his face and the words won’t come. “Give me a second,” says Roger Parrish, flushed and struggling to talk about the death of his daughter.

There is a long silence before he manages to swallow the pain, clear his throat and speak of Jo. “It’s been 25 years, I should be able to do this...” Her mother breaks in. “The time doesn’t make any difference. It gets worse.”

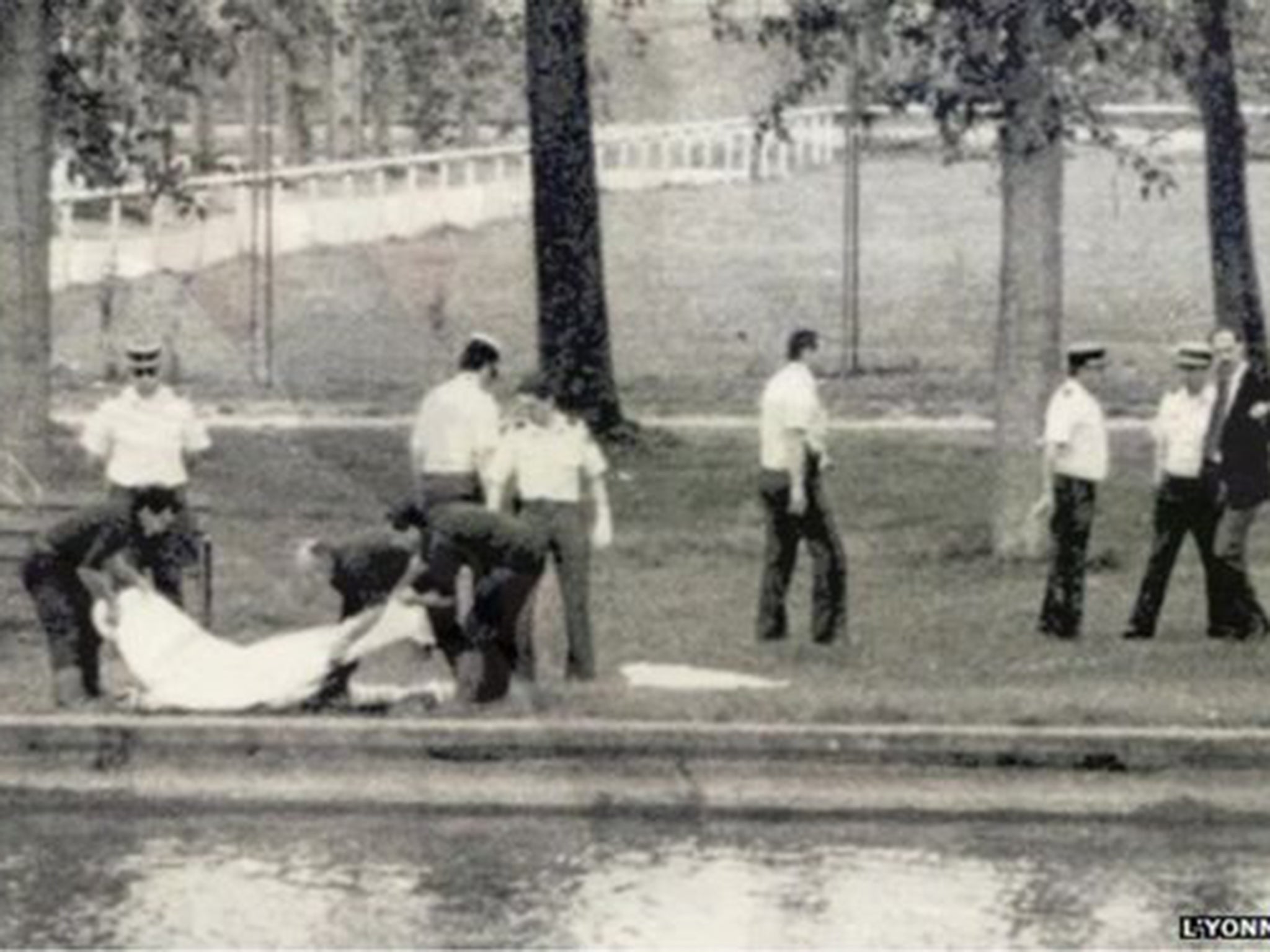

They have both carried these terrible feelings of grief, anger and frustration for such a long time. The body of Joanna Parrish was found in a river in France way back in 1990. She had been stripped, beaten, bound and strangled.

Jo was a 20-year-old language student from Leeds University, who was just coming to the end of a placement teaching English at a lycée in Auxerre. Her death made front-page news, but that was a quarter of a century ago. Margaret Thatcher was still Prime Minister. And here’s the thing: 25 years later, Jo’s parents are still waiting for the French police to catch her killer. Or let them know the latest news from the investigation. Or communicate in any way at all.

“We have heard nothing from anyone since the year before last,” says Roger, who describes their experience of French justice as a nightmare Kafka could have written.

Pauline Murrell, his former wife, compares the investigators to the bumbling Inspector Clouseau in the Pink Panther movies. “Absolute cock-ups from beginning to end. This is Clouseau-esque. I’ve said it in France. They knew what I meant.”

They split up as husband and wife around the time of Jo’s death, but remain united in grief all these years later, sitting at either side of the kitchen at Roger’s cottage in Newnham on Severn, the village where they both live in Gloucestershire.

Back in May, they tried and failed to meet the latest juge d’instruction in charge of the case. Now in this exclusive interview they reveal that they have written to her pleading – for one last time – to be allowed to know what is going on.

“This year is the 25th anniversary of Joanna’s murder. We were disappointed not to have been able to meet you,” says the letter addressed to Mme Sabine Kheris at the Tribunal de Grand Instance de Paris.

“A source of ongoing stress and frustration to us is our lack of up-to-date knowledge of what is being done by the French authorities in respect of the investigation. Is it still active? Are there any new leads? What is the position regarding DNA evidence? If this no longer exists, what has happened to it?”

Their lawyer in France assures them the case is not closed. Earlier this year their MP, Mark Harper, took it up with the Foreign Secretary, Philip Hammond, who said he would raise it with the French Ministry of Justice and report back. “We have not heard anything more than that. So we are literally in limbo,” says Roger.

“You’re just banging your head against the table the whole time. We’ve done everything we can to bend over backwards to say, ‘We’ll come to France when you want us to come, just let us know.’ There’s no response. Nothing. You do start seething.”

On Saturday week they will travel to Leeds University, where Jo studied French and Spanish, to meet her friends from those days. Together they will plant a red oak tree in her memory and read a statement from the Chancellor of the university, Lord Bragg.

“The murder of Joanna Parrish was exceptionally cruel,” Lord Bragg says. “By all accounts she was a remarkable young woman, well set on what would have been a deeply worthwhile and flourishing career, and the pain of her death must be intensified by the fact that the murderer(s) have never been brought to justice.”

Roger and Pauline have spent a small fortune going to France and hiring lawyers over the years. “The attitude seems to be, ‘If we ignore them they’ll go away.’”

Today the sunlight is flooding in through the open door, the birds are singing in the garden and the world seems too lovely for such cruelty as their daughter’s murder. But that is also how it was on 17 May 1990.

They were in their forties then, proud parents of a teenage son called Barney and his 20-year-old big sister. There’s a photograph of Jo looking stylish in a long raincoat, with her black hair cut in a bob, by the river Yonne in Auxerre.

Her mum and dad were just about to visit when she died. “We were going to bring back all her stuff, including her duvet and teddy bear, while she went on to Czechoslovakia to see her boyfriend, Patrick,” says Pauline, now 70 , whose eyes are full of hurt and potential tears.

“Lovely Patrick comes and puts flowers on the grave every year. He is now married, with two little girls, but he still comes.”

Roger is a dapper, silver-haired man of 72 who remembers being at work at the Land Registry in Gloucester that day 25 years ago, when two police officers arrived. “They said, ‘Jo’s body has been found in the river.’ For half a second I thought, ‘Right, OK, which hospital is she in?’ Then the reality dawned on me: they said it was her body. A lot of things are blacked out after that.”

Next, the police went to see Pauline. “I went numb. I looked out of the office window at the river there and I thought, ‘This is not possible.’”

They were together in the house when their son Barney came home from school. What did they say? Pauline’s voice drops to a tiny, faraway whisper. “Jo’s not coming home.”

Barney was three years younger. “Jo was a guiding light for him, really. She was bright, inquisitive, hard-working, very kind. Gentle. She probably had more influence on him than either of us. Her death messed up our son’s head, for a long time.”

Barney was too shocked to weep at first. “I remember having my arm around him saying, ‘You are allowed to cry,’” Pauline recalls. “I couldn’t cry then. I can now. You can’t stop me sometimes.”

Now grown up with a family of his own, Barney has created a social media campaign calling for people to help get justice for Jo.

They were advised not to go to France until their daughter’s body had been brought home, which took three weeks. When Pauline did get to Auxerre, she was not impressed. “Right from the beginning, they lied to us. I asked the investigating magistrate if my daughter had been raped. He said, ‘No, I guarantee she was not raped.’”

That was not true. “Within a fortnight it was in the French press that she had been raped, because the laboratories in Paris had said yes. That was awful.”

Roger sighs and says, “You want people to tell you the truth, not what they think you want to hear.”

Magistrates have come and gone since then. Most have been fantastic, welcoming and helpful, they say; but those in recent years have been silent or evasive, even in person.

“I’m quite calm normally, but I sit in those meetings and I am ready to blow,” says Pauline. “I say, ‘You cocked it up right at the beginning! It’s about time you got your act together!’”

They claim the area where the body was found was never properly sealed off and the mayor and other local officials wandered all over it, contaminating evidence. They also understand the DNA samples taken at the scene have been lost or corrupted.

“Most of the leads have fizzled out or we have had reassurance that the person wasn’t responsible,” says Roger. But everything seemed to change in 2005 when Michel Fourniret and Monique Olivier were arrested in Belgium.

Fourniret confessed to kidnapping, raping and murdering nine girls over a period of 14 years, and is serving life in prison. His wife, Olivier, sometimes picked up young women for him as she drove along in their car with their baby son in the back, and is also in jail.

“She appeared to come out with a statement suggesting she was present at the murder of a young woman in Auxerre in 1990,” he says. “The time, place and other details fitted pretty much what happened to Jo. The following day our house was surrounded by satellite vans and reporters. It appeared that this was the light at the end of the tunnel.”

However, Olivier withdrew her statement, claiming to have made it under pressure from an investigator. “We are pretty desolate about that.”

Roger and Pauline would like Fourniret and Olivier to be questioned again, with a British police officer involved this time. “You hear of it happening in cases like the McCanns, but they have more friends in high places than us,” she says.

Those friends included Rebekah Brooks, then the chief executive at News International, who was accused of threatening to put the Home Secretary, Theresa May, on the front page of The Sun every day until she launched a fresh British police investigation into the disappearance of Madeleine McCann.

She denied using threats and called it persuasion. Whatever it was, her friendship with David Cameron must have helped. The inquiry took place.

Jo’s parents want the French to tell them what became of the investigation into a lorry driver called Thierry Villetard, who lived near the school where Jo taught in Auxerre. He is currently in prison for sex crimes.

Meanwhile, Jo’s friends from university are keen to reclaim her memory. “Jo was a lively, funny, kind and gentle person, someone who could always make me smile.

“But for ages, every memory I had of her was tainted by the horror of how she died and the awareness that she was no longer there to share our journey,” says Rose Anderson, one of the organisers of the tree-planting ceremony on 26 September.

They studied French together and were in the same halls of residence. “We can never undo what happened to Jo, but by remembering her for the wonderful person she was, not just as a murder victim, we feel we are gradually bringing her memory back into the light and restoring what was desecrated.”

Roger and Pauline say they are “touched and honoured” by the kindness and loyalty of her friends. But do they think there will ever be justice for their daughter?

“I don’t think I will ever give up hope, but I think it is unlikely,” says Roger. “If it’s purely down to the French investigative teams, it’s possible we won’t get an answer,” says Pauline, before reflecting on the years that have gone by.

“I lived in Spain for a while. I haven’t just sat here and rotted. But it doesn’t make any difference where I am in the end because she’s there. I can hear her voice, I can see her face, just as she was then.”

She smiles at the thought of her daughter and summons strength.

“Jo wouldn’t have stopped. If this had happened to us or to Barney, she would have kept going. So we will keep going.”