I met one of the UK’s most notorious mass murderers: is it time to revisit his conviction?

Nearly four decades since the slaughter of five family members at White House Farm, new questions have been raised about the conviction of murderer Jeremy Bamber. David James Smith, who has followed the case for years, asks if there’s any truth to his claims of innocence

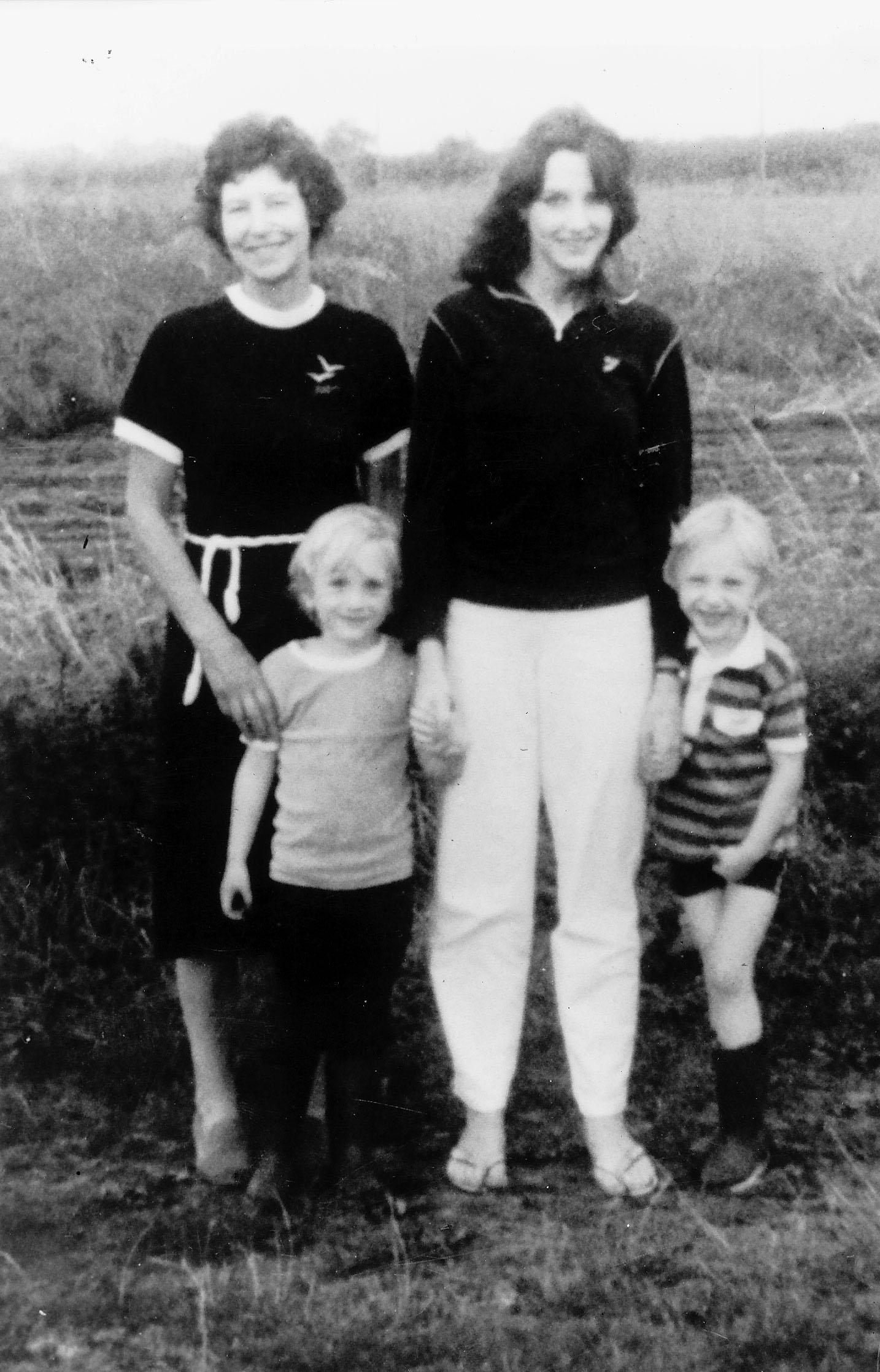

Nearly 39 years ago, in the early hours of 7 August 1985, five members of the same family died by gunshot wounds at White House Farm in Tolleshunt D’Arcy, Essex. The victims were Nevill Bamber, aged 61, his wife June, also 61, their adopted daughter Sheila Caffell, 28, and her twin boys, aged six, Nicholas and Daniel.

The police recovered 25 bullets, which had been fired from a German-made Anschutz .22 rifle, owned by Nevill. The weapon was found on Sheila’s body, giving the appearance that she had killed the others first, and then herself in a case of murder-suicide.

The surviving family member, who lived nearby, was Nevill and June’s adopted son, Jeremy Bamber, then aged 24. Just over a year later, on a majority verdict of 10-2, he was convicted of all five murders.

He remains in prison serving a whole life order, from where he continues to protest his innocence, aided by a team of activists organised as the Jeremy Bamber Campaign group.

The case of Jeremy Bamber is in many ways a quite simple conundrum. Either he is, as his many supporters see him, an icon of the miscarriage of justice movement in the UK – an innocent man, repeatedly failed by the system, wrongly imprisoned for most of the last four decades after being fitted up for five murders, which he will never stop protesting; or – perhaps equally unconscionable – he has been gaslighting all those people who believe in him and his cause, tying up the criminal justice system in knots of agonised review and decision-making, taking up thousands of hours of judicial and legal resources that could have been better spent elsewhere, persisting in his claims which he well knows to be false, having callously sought to stage the scene and frame his sister Sheila after he had murdered her.

One of those propositions is true. Jeremy Bamber is the only person alive who knows which one it is.

No wonder the case continues to fascinate. When I went to interview Bamber in prison some years ago, I agreed to give him an objective hearing, to put his case in a balanced exercise of reporting. He was pleased with the result, though told me in a letter that his fellow prisoners had ribbed him over my descriptions of his lumpy physique.

I was on his Christmas card list for a year or two and then we dropped out of contact, though I have continued to follow his case and speak about it occasionally in documentaries.

I left journalism and became a commissioner at the Criminal Cases Review Commission. I would see his supporters regularly at miscarriage of justice events – team Bamber in matching T-shirts bearing photos of Jeremy.

In their world, you were either for Jeremy or against him. I knew they were unhappy with the book The Murders At White House Farm by Carol Ann Lee, and the six-part television drama White House Farm. The series, especially, took Bamber’s guilt for granted, and depicted him, in its portrayal by the actor Freddie Fox as greedy, arrogant and ruthless.

It may or may not be significant that the epic New Yorker article published this week, over 16,000 words, does not find room to name the campaign, and does not reference the book or the drama.

The article recognises that Bamber’s only hope of a route back to the Court of Appeal lies through the Criminal Cases Review Commission, and quite rightly reflects on the state of the CCRC in the aftermath of its failings in the case of Andrew Malkinson, who served 17 years in prison for a rape he had not committed.

One contributor to the article is quoted as saying that the CCRC “must know this is an unsafe conviction, to put it mildly. But they do not want to refer it”. This is just one more conspiracy theory to add to the many that already beset Bamber’s case.

It has been Jeremy’s position from the beginning that the police, his girlfriend Julie Mugford and his wider family who stood to gain financially from his conviction, have all lied and conspired against him. His challenge, as he would see it, is to raise sufficient doubt for the CCRC to refer the case, again, back to the Court of Appeal. As some lawyers might tell you, it is not necessary to prove his guilt or innocence, only that the case against him was profoundly flawed, either, say, through police malpractice or legal error.

In fact, he might be walking free now, if he had conducted himself differently in the aftermath. His haughty, indifferent demeanour attracted the suspicion of some of his wider family, while apparently going unnoticed by the original senior investigating officer, DCI Taff Jones, who believed Sheila had killed everyone, including herself, and threw Jeremy’s relatives out of his office when they came to tell him of their concerns.

DCI Jones did not bother much with the niceties of forensic investigation or preserving the scene and handed the house back to the family. June Bamber’s sister Pamela was married to Robert Boutflour, and it was he and their two adult children, David Boutflour and Ann Eaton who were clearing up at the house when they discovered a silencer in the back of a gun cupboard.

The silencer revealed some blood that matched Sheila’s and flecks of paint that matched the shelf over the Aga in the kitchen, where it appeared that Nevill Bamber had fought a life-and-death struggle before being overpowered by his killer.

The silencer was Bamber’s undoing. If the silencer was on the gun it made the weapon too long for Sheila to have put the barrel under her chin and still reached the trigger to shoot herself. In the prosecution case, Bamber realised this at the last minute, while staging the scene, and hurriedly hid the silencer in the back of the cupboard.

When I met Bamber all those years ago, I formed a picture of him in his cell with a tower of papers in file boxes, scouring documents for any anomalies that might boost his chances of a new appeal

This was the 1980s and they did things differently then. The silencer was not immediately protected and preserved. It was wrapped in some tissue and taken home by Ann Eaton and later transported to the police station by an officer, who carried it in a piece of cardboard tube.

The finding has been contested by Bamber ever since. Meanwhile, Julie Mugford discovered that he had slept with one of her best friends and went to the police to say he hated his parents and had been discussing killing them for some time. That evening he had called to say it was “tonight or never”.

Mugford testified against Bamber at trial, sold her story afterwards to the News Of The World and then left to start a new life in Canada, rarely speaking about the case since. There were questions at the time about precisely when she had signed up to the newspaper – if it was before her court appearance it might have tainted her account because she had a financial stake in getting a conviction – but nothing has ever come to light.

Bamber has been through many teams of lawyers over the years, including at one stage the colourful Giovanni di Stefano who went to prison himself for acting as a lawyer when he was not qualified.

After Bamber’s two-stage appeal failed, following conviction, he was already applying to the Home Office for a review in 1997 when the CCRC was launched. And it did eventually refer his case back to the Court of Appeal for a lengthy hearing that considered 16 separate grounds in 2002.

The main plank of the appeal was DNA evidence that questioned the authenticity of the silencer, but the court rejected that and all the other grounds, setting out its reasons over 101 pages.

Bamber applied to the CCRC unsuccessfully in 2004 and 2009. He challenged the CCRC’s 109-page decision of 2012 at Judicial Review but that was rejected. He currently has a new lawyer, a skilled appeals specialist, Mark Newby. And he has a new application at the Commission which I believe may be focused, among other things, on new ways to challenge the evidence of the silencer.

The New Yorker article raises questions about the night of the killings and re-examines longstanding suggestions that someone was alive in the house while Jeremy was outside with the police, who waited several hours to go in, because they believed his sister might be alive and armed inside.

This was what Jeremy had told the police in a phone call at around 3.30am, when he claimed his father had called him from the house to say that Sheila had “gone berserk with a gun” before the line went dead.

There was no evidence, other than Jeremy’s account, of the call, but the phone at the farm was off the hook and BT were able to listen in. All they could hear was a dog barking but a police officer later took over listening and, says The New Yorker, he heard other sounds of movement and even a 999 call being made.

The officer told the magazine he had never seen an unsigned statement in his name, in which he appeared to deny hearing any sounds until the police went in. The statement contradicted his recollection, he said.

If Bamber was the killer, everyone in the house was long dead by then, so any suggestion of activity could undermine the prosecution, although Julie Mugford’s testimony and the evidence of the silencer would still remain.

When I met Bamber all those years ago, I formed a picture of him in his cell with a tower of papers in file boxes, scouring documents for any anomalies that might boost his chances of a new appeal.

He told me about a photo of the kitchen floor where there were no flecks of paint and how that was inconsistent with the prosecution’s account of the silencer scraping the underside of the shelf as he struggled to overcome his father. He had recreated the scratches in the prison workshop with a fellow inmate. He was sure it would help, but it never led anywhere.

I remember the interview mainly for the surreal moment, after a couple of hours, when we stopped for lunch, and two or three prison officers, my minder from the Ministry of Justice, Bamber and I sat together and ate from a tray of rolls and sandwiches provided by the prison, making small talk for a few minutes before the interview resumed. He was easy to chat with, charming, present and with no trace of the psychopath one might imagine to be lurking just beneath the surface.

I just couldn’t make him out. Or his case. Perhaps one day, the question of his guilt will be tested again in court, but not I think quite yet.

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks