Forensic science: How its use revolutionised the way we detect crime

Science Editor, Steve Connor, explains why forensic evidence has become so important

The Chinese military general and philosopher Sun Tzu once famously solved a murder in a village by asking all its residents to bring out their sickles and leave them in the sun. Eventually, flies settled on one particular sickle and the murder weapon, and the murderer, were identified.

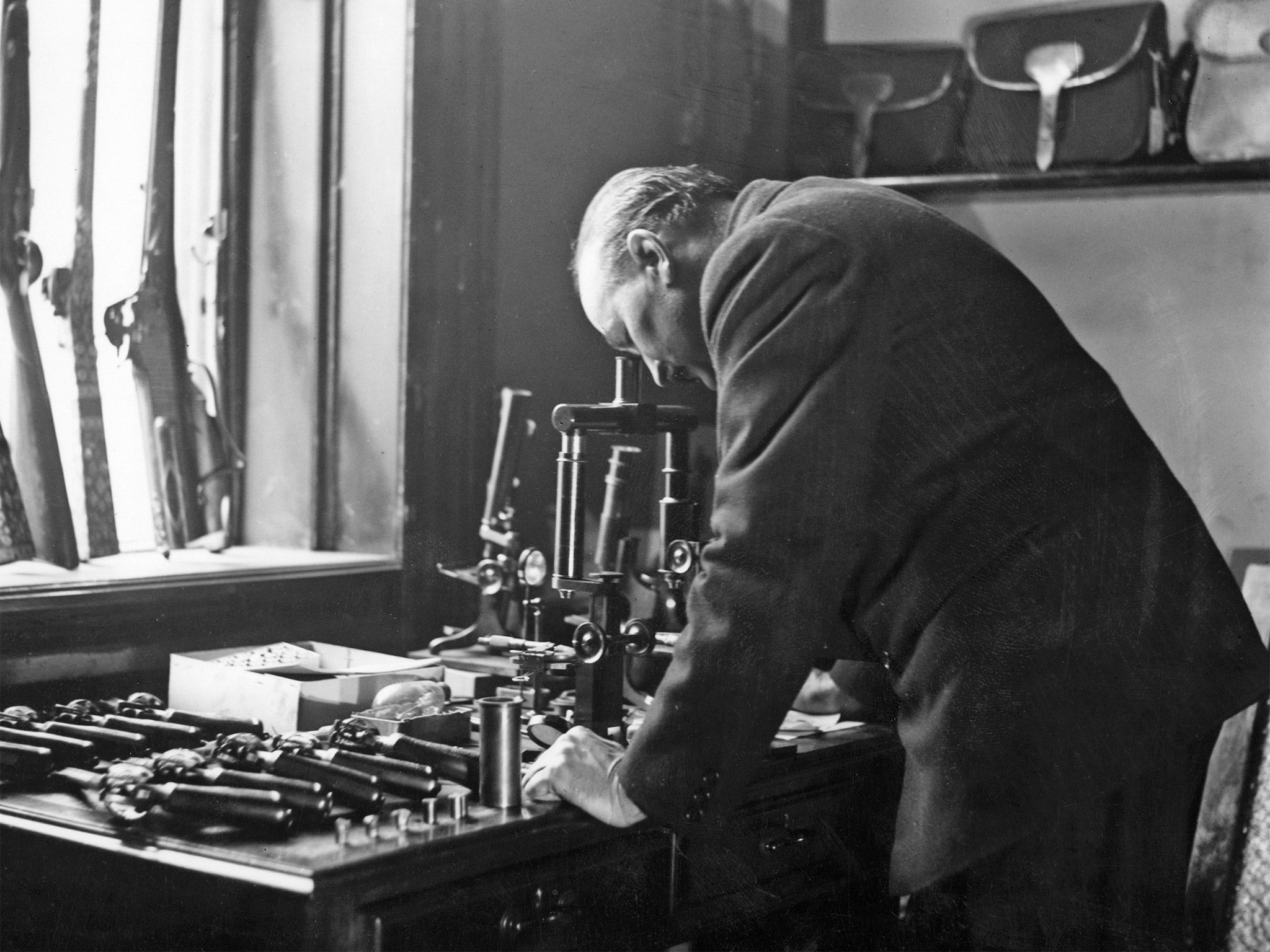

This early example of forensic science, which goes back 2,500 years, illustrates perhaps the single most important function of forensics – to find the scientific evidence that links a suspect to a crime. Identifying the murder weapon is just one part of the process.

The Forensic Science Service laboratories in London, for instance, had a deep water tank in a tube that ran from one floor of the building to another, into which its scientists would fire rounds from various guns. The bullets would be recovered from the bottom of the tank, undamaged apart from the unique microscopic scratches left on the casing by the gun barrel – enabling the scientists to link the gun to other crimes where only bullets had been recovered.

At the end of the 19th century, forensics was revolutionised by the discovery and classification of human fingerprints. And in the 1980s, Sir Alec Jeffreys at Leicester University invented a way of detecting the identifiable differences in human DNA, which became known as DNA fingerprinting. Rather than relying on conventional fingerprints, forensic scientists could now use the tiniest fragments of human tissue – from single hairs to a microscopic spot of blood or semen – to link someone to a crime scene.

DNA sampling is now routine whenever someone is arrested and, like conventional fingerprints, the police have built up an extensive computer database to search for possible matches with previous samples and suspects.

But, like other areas of science, forensics has suffered its fair share of embarrassing mistakes.

One of the most famous examples was the case of the “Maguire Seven” who were charged and convicted in 1976 of possessing nitroglycerine, allegedly used to make IRA bombs. The prosecution evidence relied almost entirely on the Griess test, invented in 1864, for detecting traces of explosive based on thin-layer chromatography.

It turned out, in subsequent research after the seven people had served their sentences, that the test was not able to distinguish accurately between nitroglycerine and nitrocellulose, a substance found in many household items, including playing cards.

The convictions of the Maguire Seven were quashed in 1991 having been wrongly convicted – and then rightfully cleared – by forensic science.

Forensic triumphs: DNA-based convictions

Colin Pitchfork became the first person in Britain to be convicted of murder based on DNA evidence.

He killed two girls in Leicestershire but a mass-screening programme of 5,000 men failed to find a match. He was finally caught after a man boasted of being paid to give a semen sample on his behalf.

Gary Dobson and David Norris were convicted of the murder of Stephen Lawrence after a months-long re-examination of fibres and tiny bloodstains nearly 20 years after the killing. Scientists from the firm LGC found a bloodstain measuring 0.25mm by 0.5mm on the collar of Dobson’s coat that matched Lawrence’s profile.

A killer was jailed in 2013 after being identified by the hairs of his own pet cat that were found attached to the victim’s dismembered body. The eight hairs were found on a curtain wrapped around the body of the dead man discovered on a beach in Southsea, Hampshire. David Hilder was convicted of manslaughter.