Ellison Report findings: After years of secrecy and misdirection, the true story of how corruption tainted the Stephen Lawrence Inquiry

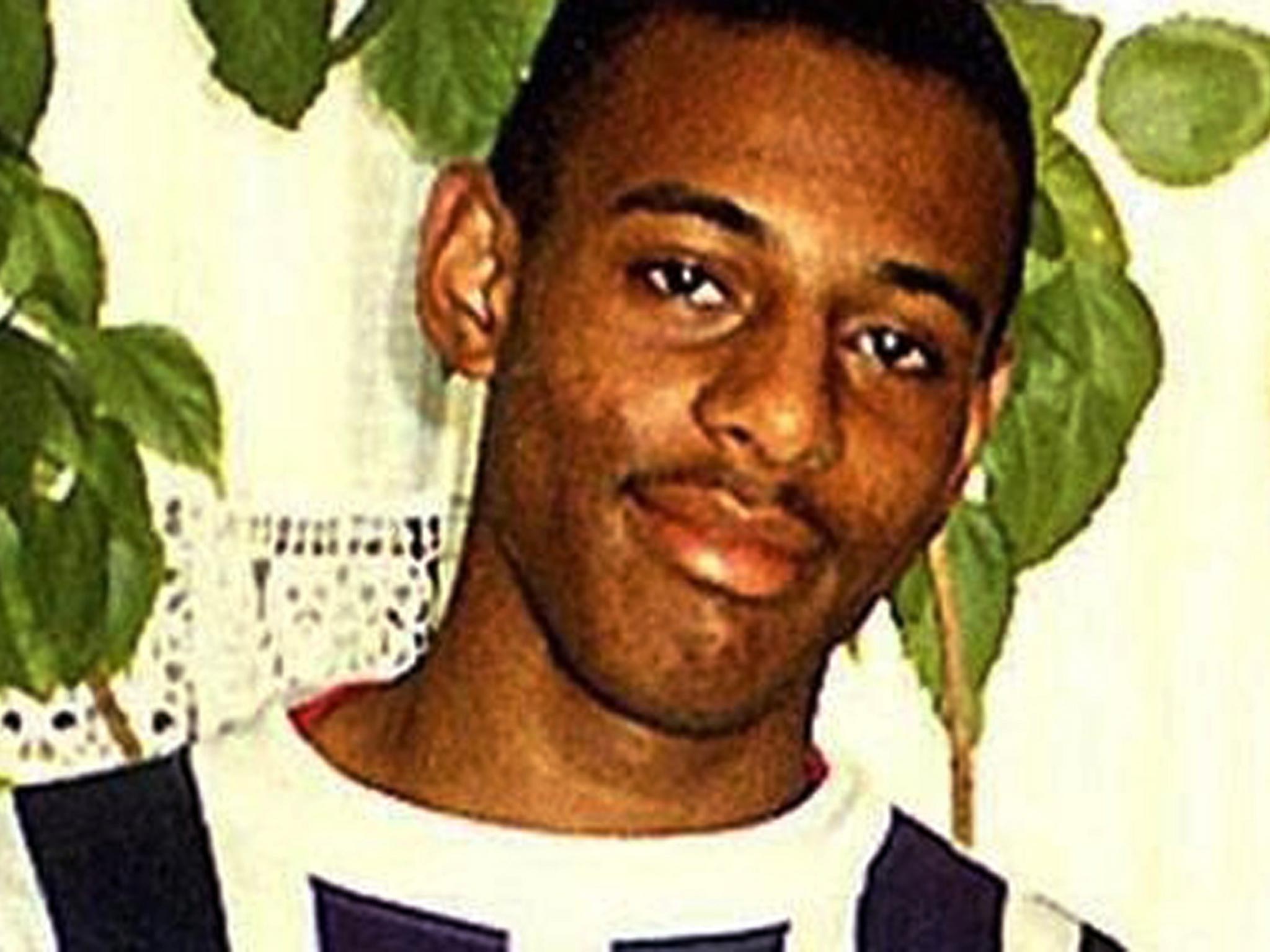

In the summer of 1998, five years after the murder of Stephen Lawrence, Scotland Yard reached a crossroads in its response to the inexcusably - and inexplicably - botched original investigation which had allowed the black teenager’s killers to swagger free.

At a safe house in an undisclosed location, officers from the Yard's anti-corruption unit began debriefing Detective Sergeant Neil Putnam, a police "supergrass" who was ready to spill the beans on a cabal of allegedly bent fellow officers.

Among those Putnam named was Detective Sergeant John Davidson, a hard-bitten Scot with the nickname "OJ" for "Obnoxious Jock" who had been a key figure on the team conducting the original investigation into the racist slaying of Stephen by a group of white youths in April 1993 close to a south east London bus stop.

The information provided by Putnam, who himself went to prison for his misdeeds, that Davidson was allegedly corrupt, mishandled informants and profited from confiscated drugs and luxury goods was of potentially crucial interest to another highly-sensitive investigation going on at the time - the public inquiry by Sir William Macpherson into Stephen's killing. Corruption had already been raised as a potential explanation for the errors, including an extraordinary two-week wait before arresting the suspects, in the early days of the investigation.

Faced with a choice between offering up its intelligence on Davidson, whose conduct had already been the subject of hostile questioning at the inquiry, and potentially even more incendiary information that it had placed an officer inside the Lawrence family camp, the Yard made its decision - silence.

Some 16 years later, the existence of that decision and its damning implications were disclosed yesterday in the report by barrister Mark Ellison QC into whether the hunt for Stephen's killers and the subsequent public inquiry were thwarted or tainted by police corruption and subterfuge.

This long and disturbingly twisty path towards the truth is signposted by a succession of ineffective previous official inquiries.

When The Independent two years ago published the investigation which revealed Putnam's latest testimony on Davidson's alleged corruption and contributed to the ordering of the Ellison review, the police watchdog conducted one such less than glittering inquiry.

The Independent Police Complaints Commission said it could find no new evidence it considered worthy of investigating to support this newspaper's contention that the Macpherson Inquiry had not been shown the full extent of the allegations against Davidson.

Ellison, who cited The Independent's investigation in his report, did find such evidence - and much more. Here is a summary of his findings:

The case against DS John Davidson

Ellison found there were "reasonable grounds for suspecting that [Davidson] acted corruptly" during the initial Lawrence murder investigation based on Neil Putnam's evidence.

Suspicion that Davidson, a pugnacious detective with a reputation for towering self-confidence in his dealings with both criminals and colleagues, was corrupt had existed both before and after his involvement with the Lawrence investigation in April 1993. The detective was criticised in the Lawrence Report, which famously accused the Metropolitan Police of institutional racism.

When Putnam was arrested in July 1998, he described in detail how Davidson was a "major player" in a ring of bent officers while both were serving in the South East Regional Crime Squad based in East Dulwich, south London. He described how they had both disposed of stolen watches, handled thieved electrical goods and taken cocaine from a drug dealer.

But the most damaging claim made by Putnam did not emerge until after he left prison in 2000, when he claimed Davidson had told him in the summer of 1994 that he had had a corrupt connection with Clifford Norris, a notorious south London gangster and the father of David Norris, who was convicted of Stephen's murder in 2012.

Putnam insisted he had revealed this to his debriefers in July 1998, who he said had recognised the import of his allegations by saying they would "blow the MPS [Metropolitan Police Service] wide apart". The Yard has long insisted there is no evidence that Putnam made these claims.

Ellison said he had found "substantial arguments" on both sides as to whether Putnam had made this particular claim, which if true would have been of extreme interest to the Macpherson Inquiry. The barrister he considered this "an unresolved issue".

A "possible link" between Davidson and Clifford Norris was to be found in a potential connection between an unnamed detective - "Officer XX" - who was known to have a corrupt relationship with the gangster, and a mutual acquaintance - "Officer B" - also suspected of corruption.

The review that Davidson would have had "many" opportunities for corrupt activity during the Lawrence investigation.

They included his role in handling an informant, "James Grant", who provided the names and addresses of the suspects within hours of the killing but whose information was not acted upon.

Ellison wrote: "As it seems to us, DS Davidson was in a position, if so minded, to act corruptly in the 'light-touch' manner we have identified. He had access to significant information and the opportunity to subtly affect the investigation, and this would plainly have been of value to those under suspicion."

But the barrister underlined the allegations against Davidson were not yet back by sufficient evidence, including independent proof to corroborate Putnam's claims.

Ellison said: "Other than Mr Putnam's potential evidence, the material available which suggests that Mr Davidson may have been corrupt in the Stephen Lawrence investigation remains 'intelligence' and not 'evidence'.

Davidson, who retired from the Metropolitan Police before he could face disciplinary charges on a separate matter, has consistently denied ever behaving corruptly.

In a statement to the review, he said: "I am not corrupt. The material set out cannot possibly be said to provide evidence of any propensity for wrongdoing on my part, no evidence of corruption in the initial investigation, and no evidence of links between myself and Clifford Norris."

The Yard's failure to tell Macpherson

The review is damning of what it said was a failure by the Metropolitan Police to pass on the full extent of its intelligence on DS Davidson, including Putnam's allegations, to the Macpherson Inquiry.

Ellison said that given Davidson's clear importance to the inquiry, the Yard should have conducted a "proper" analysis of all information it held and had shown an extraordinary lack of curiosity about the information Putnam was likely to hold on his colleague.

The barrister wrote: "It is a source of some concern to us that nobody in the MPS who was aware of the detail of what Neil Putnam was saying about Mr Davidson appears to have thought to ask him about Mr Davidson's motives in the Lawrence case."

The review said it could not reach a conclusion as to whether the Yard had deliberately withheld the information from Macpherson or there had simply been a "lack of joined up thinking".

But it found there were "clear defects" in the level of what it revealed. Ellison found: "The MPS held material of some potential importance to the determination of the true motives behind John Davidson's deficient investigative work on the Stephen Lawrence murder investigation and had not revealed it."

The missing evidence

In 1993, the then-Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police set up Operation Othona, one of the most comprehensive and secure anti-corruption investigations in the history of Scotland Yard.

The operation ran until 1998, gathering a vast database of intelligence on officers suspected of corruption.

But when the Ellison review sought to carry out the "fairly fundamental task" of trying to establish what material should have been disclosed to the Macpherson Inquiry, it found it had been destroyed, mostly in a "mass shredding" in 2003.

The only material recovered after a year of searching by the Yard was a hard drive found in an IT department last November and three reports summarising the intelligence held by the IPCC and a senior detective.

Ellison wrote: "If the MPS searches for all relevant material cannot reveal such reports of central significance to the issue of possible corruption in the Stephen Lawrence murder investigation, there must be serious concerns that further relevant material has not been revealed."

Other corrupt officers

The Ellison review found there were no grounds for suspecting that other officers involved in the original inquiry were corrupt. Among the officers whose cases were scrutinised was former Yard commander Ray Adams, who faced hostile questioning at the Macpherson Inquiry and was accused of trying to influence the Lawrence investigation.

But the review found there was no "reasonable grounds" for suspecting he had acted corruptly.

The police spy in the "Lawrence family camp"

Scotland Yard planted a "spy" in heart of the campaign to support the parents of Stephen Lawrence, according to the Ellison review.

The existence of the undercover officer from the Met's highly covert Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) in the "Lawrence family camp" during the Macpherson Inquiry had not been previously acknowledged is one of the most shocking findings of yesterday's report.

During his time posing as a supporter of the family, the agent - known only as N81 - and other undercover officers provided information including "discussion of the progress, reasons and details of the decisions made by the Lawrence family" as they fought their campaign to force the Met to bring their son's racist killers to justice. They also gathered "some personal details" concerning Stephen's parents, Neville and Doreen.

The SDS, part of the Met's Special Branch, had been established in the 1960s to penetrate radical groups such as animal rights protesters or political extremists and was eventually disbanded in 2008.

Ellison, who prosecuted the two men - David Norris and Gary Dobson - convicted of the Lawrence murder in 2012, also criticised a meeting between N81 and Richard Walton, who is now the Yard's head of counter-terrorism but was at the time part of the team responsible for making the Met's submissions to Macpherson.

The lawyer said this secret channel of communication was "wrong-headed" and "inappropriate".

He added: "The reality was that N81 was, at the time, an MPS spy in the Lawrence family camp during the course of judicial proceedings in which the family was the primary party in opposition to the MPS."

Ellison said there could have been no conceivable "public order" justification for the meeting, which happened in August 1998, and said if it had been disclosed it could have led to "serious public disorder".

Duwayne Brooks

The SDS agent also gathered intelligence on Duwayne Brooks, the friend of Stephen Lawrence who was with him on the night of the murder, according to the review.

Among the information gathered by the unit was material on divisions between Brooks and the Lawrence family, his approach to a rape case which later collapsed and his expectations from a civil damages case against the Met.

The lawyer found such information had "little value in terms of legitimate public order concerns" and should have been terminated but continued until 2001.

The review also strongly criticised a decision to covertly record a meeting between Brooks and his lawyer, saying that although it had not been illegal, it was neither necessary nor justified.