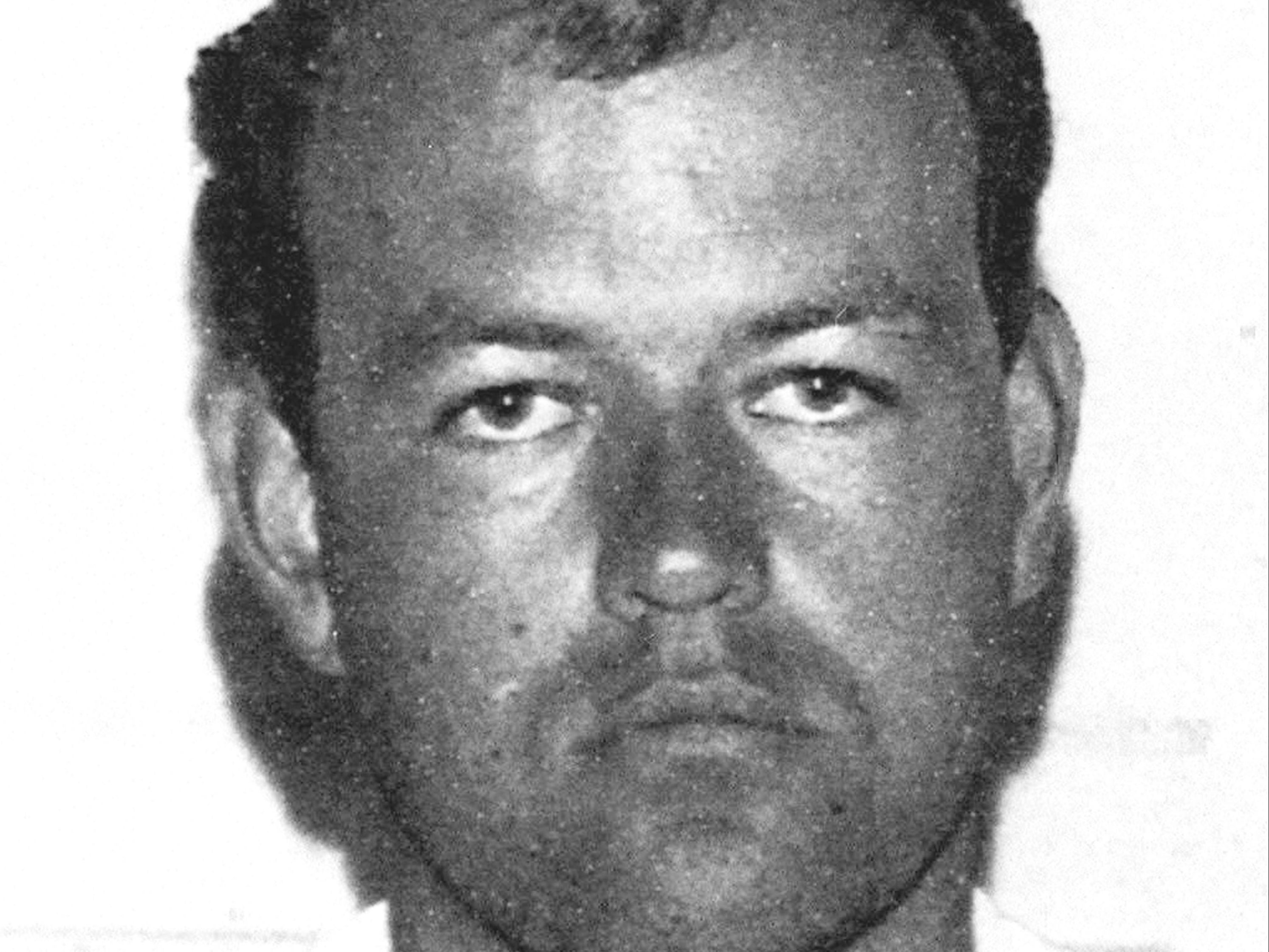

Colin Pitchfork: Murderer who raped and killed schoolgirls to be freed after government loses legal challenge

Pitchfork had raped and killed one of his victims while his baby son was sleeping in the back of his car

A double child murderer and rapist is set to be freed from prison after a challenge against his release was rejected today.

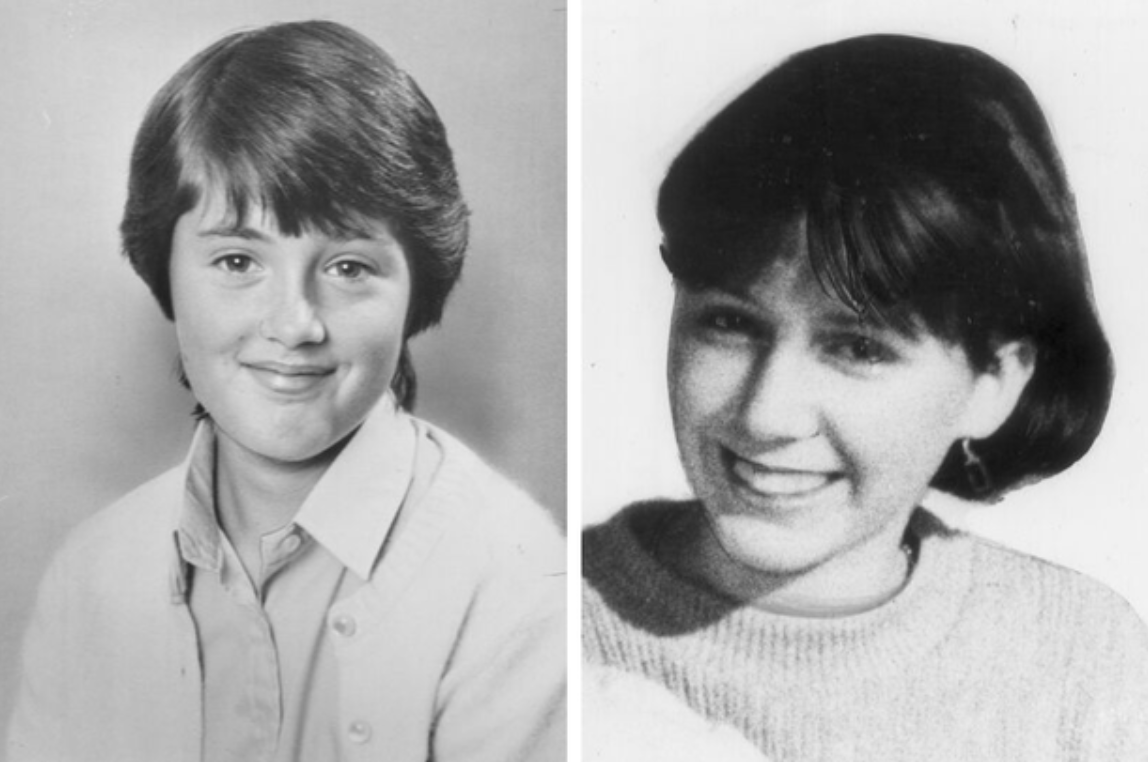

Colin Pitchfork has served 33 years in prison for raping and strangling 15-year-olds Lynda Mann and Dawn Ashworth in two separate attacks in the 1980s in Leicestershire.

In 1988, he became the first person to be convicted of murder with the help of DNA evidence. He admitted two murders, two rapes, two indecent assaults and conspiracy to pervert the course of justice.

Pitchfork, 61, who calls himself David Thorpe, was a baker aged 22 and married with two sons at the time of the first murder. He grew up in rural Leicestershire and lived in the village of Littlethorpe.

In November 1983, in the neighbouring village Narborough, he left his baby son sleeping in the back of his car to rape and strangle Lynda. He then drove home and put his son to bed. Lynda’s body was found the next morning dumped along a footpath.

In July 1986, in nearby village Enderby, he raped and murdered Dawn. The pathologist who examined her body, that was found hidden under branches in a field two days after the attack, said it showed signs of a “brutal sexual assault”.

An investigation initially led to the wrong person – a 17-year-old who had learning difficulties and had known Dawn. During questioning he would repeatedly say he had killed her and then withdraw the admission. Tests later showed that his DNA did not match that of the same person who attacked Dawn and Lynda.

Police then launched the unprecedented operation of having more than 5,500 blood samples of men screened. Pitchfork had initially evaded justice by persuading a colleague, Ian Kelly, to take the test for him using a forged passport as ID. Pitchfork told Kelly that he wanted to avoid being harassed by police because of prior convictions for indecent exposure.

But this plot was foiled after a woman overheard Kelly in a pub confessing to being paid £200 by Pitchfork to take the test.

Pitchfork was arrested. Under questioning, he had admitted to having exposed himself to more than 1,000 women.

His profile matched DNA left at both crime scenes and he pleaded guilty to the murders in 1987. He was sentenced to life the following year. The judge said the killings were “particularly sadistic” and he doubted Pitchfork would ever be released.

A psychiatric report, which recorded a “personality disorder of psychopathic type accompanied by serious psychosexual pathology”, warned that Pitchfork “will obviously continue to be an extremely dangerous individual while the psychopathology continues”.

In 1979, he had forced a 16-year-old girl into a field and sexually assaulted her before fleeing when he thought someone was approaching. Pitchfork also forced a 16-year-old girl to perform a sex act on him while threatening her with a screwdriver and a knife to her throat in October 1985.

The Parole Board has now ruled that he is “suitable for release”, despite previous requests being denied in 2016 and 2018.

In June, justice secretary Robert Buckland asked the board, which is independent of the government, to re-examine the decision under the so-called reconsideration mechanism.

The reconsideration mechanism, introduced in July 2019, allows the justice secretary and the prisoner to challenge the board’s decision within 21 days if they believe it to be “procedurally unfair” or “irrational”.

Victims and members of the public can also make a request via the minister.

On Tuesday, the Parole Board announced the government’s application had been “refused” and that Pitchfork will be released.

It comes after his 30-year minimum term was cut by two years in 2009. Pitchfork was moved to an open prison in 2017 and it emerged that he was released for unsupervised days out.

A statement read: “The Parole Board has immense sympathy for the families of Dawn Ashworth and Lynda Mann and recognises the pain and anguish they have endured and continue to endure through the parole process.

“However, Parole Board panels are bound by law to assess whether a prisoner is safe to release. It has no power to alter the original sentence set down by the courts. Legislation dictates that a panel’s decision must be solely focused on what risk a prisoner may pose on release and whether that risk can be managed in the community.

“As made clear in the reconsideration decision, release was supported by all of the Secretary of State’s witnesses during Mr Pitchfork’s review.”

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks