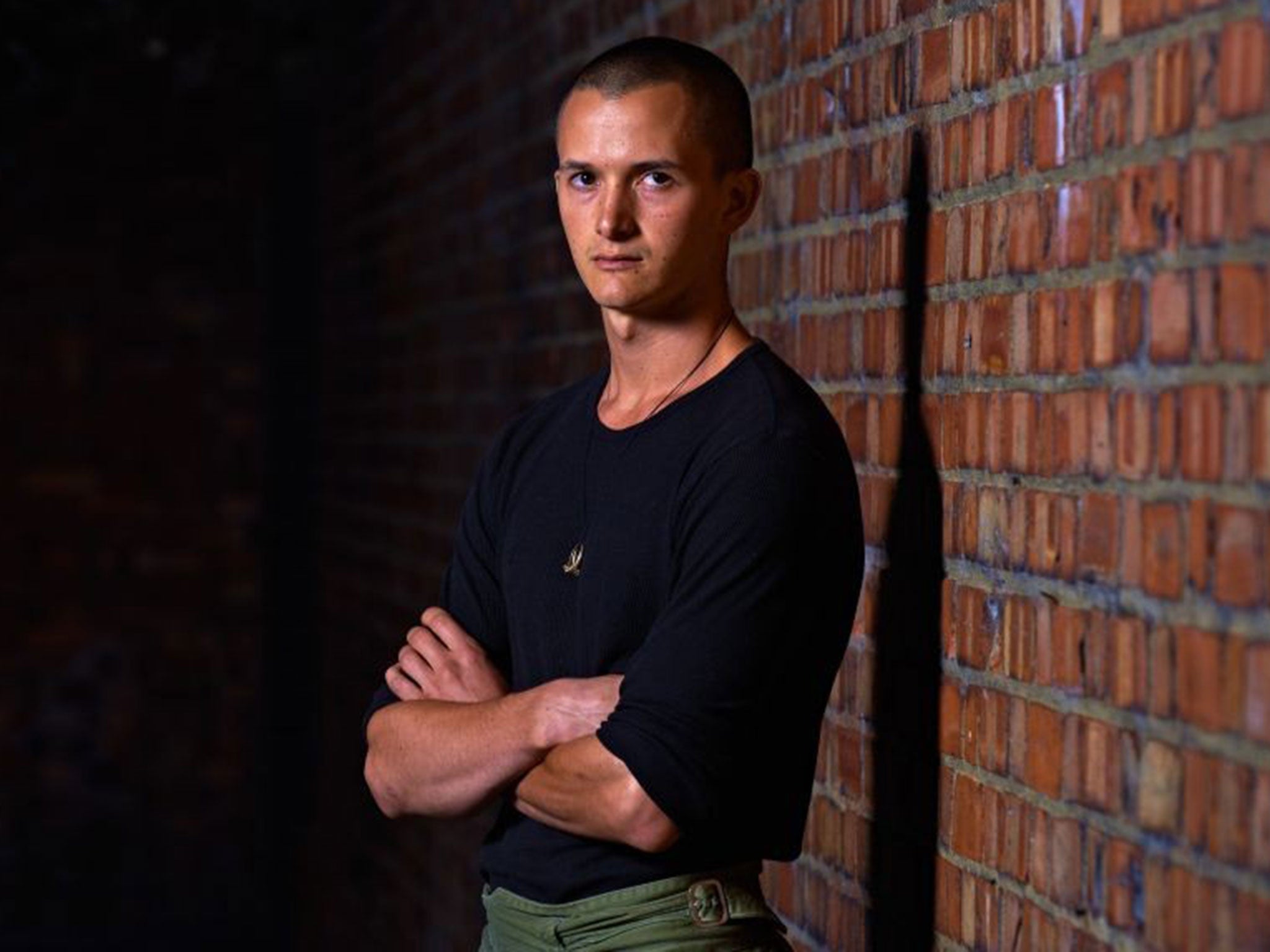

Charlie Gilmour: 'I wondered if I would end up killing myself in jail'

In a high-profile case in 2011, Charlie Gilmour was sentenced to 16 months in prison for violent disorder in the wake of widespread student protests against the coalition government's programme of austerity. He spent four months inside before being released to spend the rest of his sentence under house arrest. Following last week's report on prison suicides, he asks how much progress we have made in the 50 years since the abolition of capital punishment

In the past eight months, more people have committed suicide in British prisons than were executed in the United States in 2013. The Prisons Ombudsman, examining the deaths of 80 inmates aged between 18 and 24, concluded that risk assessments and monitoring arrangements for those at risk of suicide were poor, and that prisons are failing to act upon families' concerns. According to the Howard League for Penal Reform, in the year to March 2014, the number of prison suicides increased by 69 per cent over the previous 12 months.

It is 50 years since Britain carried out its last official execution, but it does not seem as if we have really come that far. When the Labour MP Sydney Silverman proposed the Private Member's Bill that eventually brought about the abolition of the death penalty, he said: "No one thinks that this Bill will carry humanity a long step forward, but it will at least place this country again proudly in the van of progress and take our country, and the world, one step, if a modest one, nearer to a saner, happier, more cheerful, more rational and civilised human society."

While the ink that marked that Bill's passage into law has been dry for decades, the blood on the hands of British justice is still fresh. Our growing prison population is being concentrated in increasingly cramped and inhumane conditions. As the Chief Inspector of Prisons told The Independent last week, it is "not credible" for the Government to deny a link between staff shortages, overcrowding, and the rise in self-inflicted deaths.

Three people every week find a way to end their lives in institutions which, purportedly at least, are meant to help rebuild them. To my cost, I have seen prison from the inside, and had a small glimpse of how spirit-crushing it can be. When I left in 2011, I remember the relief I felt at having managed to get out before the cuts really kicked in. Since then the coalition government has overseen the closure of 18 prisons, with no corresponding decrease in the prison population. Rather, the number of prison officers has been cut by 30 per cent. This means that there is nobody to let prisoners out of their overcrowded cells in the morning or supervise education and exercise throughout the day. And if the consequent monotony and squalor become overpowering, there is nobody to cut them down from the wall bracket either. "Over the past 18 months," said Frances Crook, CEO of the Howard League, "the system has gone into total meltdown."

Even back in 2011, the system seemed designed to break, rather than mend. One young man who had been transferred in from a psychiatric unit was, the doctors told the administration, at serious risk of suicide and would need constant supervision. The officer on duty outside his cell – a cell with no bedding, in which the light could never be turned off – could frequently be heard snoring, his copy of The Sun over his eyes. That man didn't kill himself during the short time I was on his wing, but having been deprived of sleep, privacy, and proper treatment for so long – and with the officer who was meant to be looking after him using suicide watch as a chance to snooze – I would not be surprised if he had eventually done so.

A report by the Prisons Ombudsman confirms that this lack of care is endemic. In one of its anonymous cases, a young man with a history of suicide attempts lost his girlfriend and a close family member on the same day – yet the authorities did not consider the possibility that he might be at greater risk of self-harm. Two days later he was found hanging in his cell.

In another instance an officer repeatedly ignored the alarm bell of an inmate on a segregation unit. He simply shut the buzzer off. When the officer eventually went to see what the problem was, three hours after the inmate had last pressed the alarm, he was dead. He was 22 years old.

These incidents demonstrate both the gross inadequacy of prison as a place to treat people suffering from any sort of mental affliction, as well over half the prison population does, and the woeful attitude of many prison officers to those under their care. There is a culture of indifference, that has led to many preventable deaths.

It's not hard to understand their position. If your job were to routinely subject your fellow man to conditions which most people would not inflict on a dog, then for your own sanity you would probably convince yourself that they are not truly human. Only the firm belief that prisoners are closer to animals could explain the number of doors I saw slammed in the faces of men begging for medication, pain relief, or medical attention, and the number of prison officers who routinely ignore emergency alarm bells, with deadly consequences.

An incident that occurred while I was in prison still makes me shudder. A man had been screaming for help all night, pushing the alarm bell and, when that elicited no response, banging a chair against the door. When, after a significant period of time, the officer on duty came to see what the problem was, the inmate told him he was suffering from severe chest pains and thought he might have had a heart attack. He needed a doctor. The officer's response was to slide a couple of painkillers under the door and ignore his pleas for the rest of his shift. "The most terrifying thing," said a friend in the cell opposite his, "was when his cries finally stopped. We knew he wasn't sleeping." In the morning, he was dead.

Prison at once dehumanises those who pass through its gates and takes away the humanity of those who run them. With far fewer prison officers around to lend a (putative) helping hand, and an even greater population for them to deal with, this antagonism has sharpened, and is now close to open warfare. The number of serious assaults on staff is at its highest since records began. Over the past three years, the number of callouts for the Tactical Response Group – the riot squad – has risen by 72 per cent. So while some prisoners are being driven to suicide and self-harm, others, who may not have been violent until this point, are being provoked to riot.

Before I went to prison I wondered if I would end up killing myself while inside. Thankfully, I had a huge support network of family and friends to see me through, and the solidarity and friendship shown by other inmates was overwhelming. Some were less fortunate. Another boy on my wing – we were two of the youngest in the prison – was going through a hard break-up with his girlfriend. She was also one of his only points of contact with the outside world. He would come into my cell almost every day for a week or so to share a cigarette and cry about his situation. One day he came in with black eyes instead of red ones. An older inmate had hit him. "Everyone in here has problems," the inmate explained when I asked him why, "and we keep them locked down. You can't have someone going around crying all the time. It might set everyone off." Some time later, I heard, that young man killed himself, too.

As the Prison Officers Association has itself admitted, our prisons are no longer fit for purpose and have become mere "warehouses". But inmates are not boxes to be stored away, or livestock to be penned in. They are human beings. Their statement implies that prisons once were "fit for purpose", but this is, of course, untrue.

Ultimately, it is society that needs reforming, not those trampled beneath it. Prisons have always been dehumanising, for everyone. This government has simply taken the idea that underpins this – the idea that some people aren't really people at all – to its logical conclusion. Even if their policies are not designed deliberately to kill, that is their consequence. The deaths we inflict now seem even crueller than the noose Silverman was so proud to have outlawed all those years ago.

How to help

There is a lot that can be done to help those inside. Writing to a prisoner alleviates boredom and, maybe more importantly, shows that someone cares. You might even save a life. The London Anarchist Black Cross (network23.org/londonabc) has excellent resources for this. Or, you can donate to Haven Distribution (www.havendistribution.org.uk/index), which provides inmates with books, or visit the Howard League for Penal Reform (www.howardleague.org) and make a donation or get involved in one of the campaigns.

Charlie Gilmour