Andy Coulson guilty in phone hacking trial: 'We need a hit. Badly' How culture of News of the World's glory days led to its downfall

Senior staff equipped themselves with a powerful but illegal tool to gain insight into the lives of those deemed of interest to the red top's readers

In April 2005, an email from Andy Coulson landed in the inboxes of his News of the World staff. Times were good for the Sunday tabloid, which had battered its red top rivals with a succession of scoops and just been named Newspaper of the Year.

But if journalists were expecting a paean of praise from their driven young editor, they were to be disappointed. Coulson felt his title was not reaching the heights of the previous 12 months, during which “the Screws” had broken stories including an affair involving Home Secretary David Blunkett as well as allegations about the marriage of David Beckham. And he was not afraid to instil a bit of fear.

Coulson wrote: “The truth is we’ve not fulfilled our brief this year. I’m not for one moment doubting your efforts but we need a hit. Badly.”

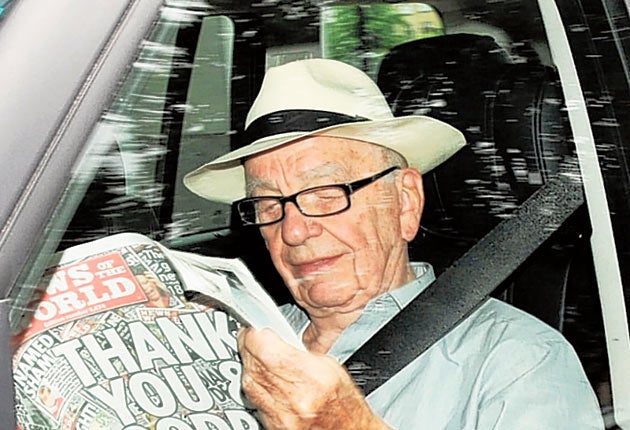

In the hard-bitten world of Sunday tabloids where reporters lived under a regime of permanent toil and were only ever as good as their last story, such ritual “bollockings” were part of the newsroom’s motivational mood music. The rule? Rupert Murdoch’s papers didn’t come second. That wasn’t how they did business.

But on the NOTW, the nation’s biggest-selling paper and fearsome leveller of reputations, the pressure to deliver that “hit” - a scoop exposing the moral turpitude and hypocrisy of fallen celebrities, sportsmen, lawmakers, preferably with a whiff of criminality - “the DNA of the paper” - was all-consuming.

This, after all, was the title that had brought low Jeffrey Archer, David Mellor and countless others; the paper where the departure of a particularly successful edition under the editorship of Coulson was often accompanied by a soundtrack of champagne corks popping in the editor’s office.

In order to release that high pressure of commercial expectation, the paper had become steadily and fatally infected by the very same turpitude, hypocrisy and criminality it was sworn to expose.

Today an Old Bailey jury decided that contagion had its origins among the group of seasoned Fleet Street veterans in day-to-day charge of bolting together the Sunday paper but knowledge of the practice had stopped at the door of Mr Coulson.

For at least six years between 2000 and 2006, senior staff sat on the newsdesk close to the office from which Coulson sent his email exhorting ever greater effort, had equipped themselves with a powerful but illegal tool to gain insight into the lives of those deemed of interest to NOTW readers.

After decades as the flagship and the cash cow of Murdoch’s British newspaper stable, the Screws was feeling the bite of problems assailing the entire news industry. With a slowly declining circulation and dwindling budgets, the NOTW’s editors and their staff were required to produce the same quantities of agenda-setting salaciousness with fewer resources.

As a result, for some the temptation to dramatically cut corners became irresistible.

Video: Coulson found guilty

In October 2000, Greg Miskiw, a Fleet Street veteran who was the NOTW’s news editor, was asked by then editor Rebekah Wade to set up an “special investigations unit” within the paper. After adding Neville Thurlbeck, another award-winning NOTW reporter and its former crime correspondent to his staff, Miskiw made another vital acquisition - a footballer-turned-private investigator called Glenn Mulcaire.

His prime talent was an extraordinary ability to blag the details of mobile phones, in particular the Direct Dial Number (DDN) and PIN to the voicemails of pretty much anyone his paymasters in Wapping desired.

With just the pressing of a few buttons, the jewel in the crown of Murdoch’s UK newspaper empire could eavesdrop on the phone messages - most of them banal, but some pure tabloid gold – that illuminated the private lives of figures from films, television, politics, sports, their aides, friends, families. Expensive surveillance operations, the relentless investigative journalism of cultivating “sources”, were redundant, replaced with a few digital clicks.

The expose of the affair between Blunkett and publisher Kimberley Quinn helped the NOTW win the coveted Newspaper of the Year award. The editor framed the citation, but behind the scenes, Mulcaire was being rewarded handsomely. Who knew? A NOTW sports feature in 2002 on AFC Wimbledon, where Mulcaire had been a player known by his nickname “Trigger” , described him as part of the paper’s investigations team.

Under a contract drawn up by Miskiw, Mulcaire, who operated variously from his home and an office equipped with six separate landlines in Sutton, south west London, was paid £1,769 a week - £92,000 a year.

By 2003, when Coulson became editor , the contract was worth £105,000.

By the time of his arrest in August 2006, Mulcaire had acquired 11,000 pages of disorganised but damning notes and 745 tape recordings which lifted the lid on six years of illegal eavesdropping. The private investigator, who at one point had coveted a role in Britain’s intelligence services, was punctilious about one aspect of his record keeping - on the top left hand corner of the note books in which he recorded the phone numbers, PINs and details of messages, he also wrote the initials of the NOTW staff member who had commissioned the “hack”.

The trial heard that between 2003 and 2006 in more than half of cases (nearly 57 per cent) the name on Mulcaire’s notes was Greg Miskiw. In 12 per cent of cases it was James Weatherup and Neville Thurlbeck had made seven per cent of Mulcaire’s “taskings”.

Initially at least, those who knew about Mulcaire’s “special inquiries” were relatively sparing and discrete about the use of the technique, which formally became illegal under the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act in 2000.

Former NOTW staff, some of them interviewed by the police and prosecution for the trial, but ultimately deemed too risky to put on the stand, told The Independent that hacking was concealed by inventing an alternative explanation for how a story was obtained - in one case it was claimed a piece was based on material overheard by an amateur radio enthusiast.

Indeed, use of the term “hacking” to describe voicemail interception only became common after the practice had been exposed. In the Wapping newsroom floor it went by other terms - “scan”, “tap”, “screw” or, simply “do” someone’s phone.

Hacking happened. This was never disputed in seven months of hi-octane adversarial combat in court 12 of the Old Bailey. News International, still engaged in the civil courts by a stream of victims, have paid out hundreds of millions of pounds in compensation and astronomically high legal bills. And after one hacking operation from 2002 came to light in the pages of The Guardian, the tide of public outrage over what happened to the family of Milly Dowler was sufficient to persuade Murdoch that the only commercial option left was to close the paper.

What is known beyond doubt is that by the time Coulson sent his email in 2005, hacking on the NOTW had evolved dramatically.

At first, voicemail interception had been as much a cost-cutting tool as a source of information. Rather than going to the expense of employing a reporter or a private detective to follow a celebrity for days on end in the hope of catching him or her attending an assignation, a rendezvous or assignation could be gleaned from an intercepted voicemail.

But in the “do anything but don’t get caught” culture of the Screws, phone hacking had become too effective a tool to use sparingly.

No longer was it the sole preserve of Mulcaire on a south west London industrial estate far removed from Wapping. Instead, the practice moved inside the offices of the NOTW itself and was conducted, according to its former royal editor Clive Goodman, on an “industrial scale”.

The police investigation into phone hacking launched in the wake of the revelations about Milly Dowler in 2011 found that by October 2005 at the latest, hundreds of calls were being routed via a “private wire” or dedicated line inside News International’s headquarters to the voicemails of targets ranging from Cabinet members to glamour model Katie Price and disgraced PR man Max Clifford.

The line, which routed calls from handsets in Wapping, was used 416 times to the mobile phone Jamie Lowther-Pinkerton, the private secretary to Princes William and Harry, and 296 times to Mark Dyer, the private secretary of Prince Charles.

Whether coincidental or not, Coulson’s email urging greater efforts preceded the zenith of hacking at the NOTW. In the space of a short few months, it formed the corner stone of the paper’s investigations into Charles Clarke, the successor to Blunkett as Home Secretary, Lord Freddie Windsor and others.

Court 12 heard detailed evidence of hacking in only a handful of cases including Jude Law, Sienna Miller, Calum Best, Andy Gilchrist; other cases were briefly referenced such as Sir Paul McCartney and Sven Goran Erikkson. In the words of one long-standing reporter: “[Hacking] became the course of first resort rather than last.”

The NOTW’s appetite for voicemail interception didn’t stop at the newsdesk. The jury were told of a parallel hacking operation run by the features department.

Indeed, with the spread of hacking came an increasingly cavalier attitude which led to its unveiling.

In November 2005, Clive Goodman, the award-winning royal editor who once took private calls from Princess Diana but was considered to be waning force and had been facing increasing demands to produce a “hit” for his editor, listened in on voicemails which revealed that Prince William had strained a tendon in his knee and also borrowed some broadcasting equipment from a journalist friend.

It was low-grade royal gossip, but it helped to fill Goodman’s weekly quota of royal titbits. But he forgot the cardinal rule of hacking - to ensure that separate “sources” were found to cover up hacking.

Royal aides rapidly reached the conclusion that Goodman’s stories could only have come from listening to private emails and called in the police. Their investigations revealed a direct link between the royal reporter and Mulcaire, leading to the arrest and subsequent jailing of both men in January 2007.

On the day of the sentencing of both men, Coulson remarked in an email to Brooks that the day was “going so well”. Sarcasm, as Coulson said it was? Or the accurate use of English by someone regarded as smart enough to be hired within weeks by David Cameron to head the Conservatives’ communications operation?

As Paul McMullan, a former features editor at the paper when Coulson first came to the NOTW, once put it: “Coulson was the hacker-in-chief. He probably told half the staff how to do it. There wasn’t just orders to “do” someone’s phone. If a story was going nowhere Andy would ask “Why haven’t you done his phone?”

Rather than an aberration, hacking became symptomatic of the singular atmosphere that presided at the NOTW - a toxic mixture of bravado, arrogance and paranoia that made techniques such as eavesdropping on private messages and paying public officials for information as the default means of survival.

As one member of staff put it: “Nobody ever felt secure there and that’s the way they liked it. On the edge, scared and insecure.”

The deliberate creation of a “shark pool” of ruthless competition in the NOTW newsroom, by which reporters’ continued employed depended on the so-called “byline count” of how many stories they managed to get in the paper, led to the deployment of ruthless, and ultimately illegal, dog-eat-dog tactics.

When one senior journalist heard that the paper’s undercover specialist, Mazher Mahmood, was investigating a story about a high-profile model working as a prostitute, he promptly phoned the woman’s agent to tip her off in the hope of killing the story. Collegiate spirit wasn’t how you got to next week.

Both Goodman and Dan Evans, the specialist hacker brought in from the Sunday Mirror, said they were warned by senior staff to find stories that merited the label “a big story, or the Big Issue”, and if they failed they might as well “jump off a cliff” in the absence of a scoop.

The “dark arts” became the NOTW’s dark side and the moral arbiter identified by George Orwell as the cornerstone of an English working class Sunday afternoon, lost its moral compass.

According to insiders, the NOTW became less a newspaper than a broker or a clearing house for reputations whereby information gleaned about individuals - from Big Brother stars to public figures - became a form of currency for access and influence exercised by editors and executives.

Shortly after the paper closed in July 2011, a former general news reporter said: “They used to call stories ‘levers’. They weren’t interested any more in using the story you’d proved or got past the lawyers. They were interested in using the story as leverage in order to get a different story.

“They used the stories to bank credit with influential people. It then made the whole raison d’etre of the place something different.”

As the trial judge Mr Justice Saunders noted, the paper fell into the trap of believing in its own importance to the extent that, in the case of Milly Dowler, it withheld information that might have proved useful to police for 24 hours to suit its own deadlines.

Miskiw, who pleaded guilty to hacking and now faces imprisonment with his former newsdesk colleagues, Thurlbeck and Weatherup, once famously remarked to a fellow NOTW journalist: “That is what we do - we go out and destroy other people’s lives.”

It is hardly a cruel irony that he can now include in that description his own life.

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks