Andy Coulson guilty in phone hacking trial: The scandal that led to self-examination unprecedented in four centuries of a free press

But how much has changed in terms of regulation? Nothing much, if you listen to some of the hacking victims

The phone hacking scandal provoked a public and political backlash of such proportions that newspapers had to submit to a process of inquisition and self-examination unprecedented in four centuries of a free press.

We saw Rupert Murdoch grovelling before MPs on the “most humble day of my life”. We saw Paul Dacre, editor-in-chief of the Daily Mail, compelled to make a rare public appearance and defend his paper’s journalism on camera.

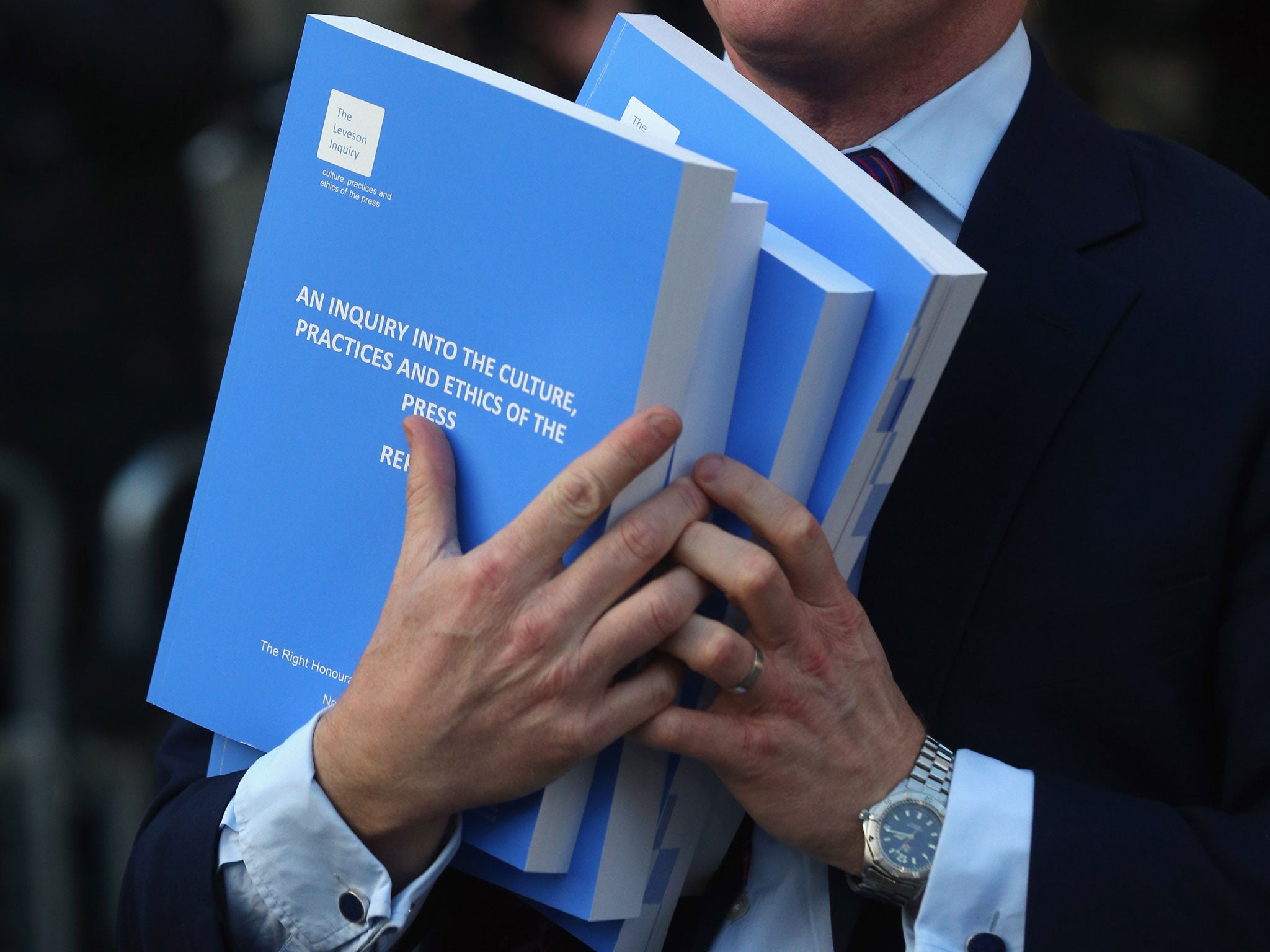

The methods of the British press were scrutinised and traduced as never before by politicians of all leading parties and during the 16-month ordeal of Lord Justice Leveson’s inquiry, which ended with a 2,000-page report and a long series of recommendations on how the newspaper industry should be reformed.

All of these developments were big news and the papers were duty bound to wrestle with the issues on their own pages and websites – though some titles did their best to pretend that the public had lost interest.

And at the end of all this, how much has changed? Nothing much, if you listen to some of the hacking victims who are unconvinced that the conclusion of the Old Bailey trial will bring meaningful reform to the British press.

The newspaper industry, on the other hand, claims to have already made great strides in cleansing itself. Its new regulatory body, the Independent Press Standards Organisation (IPSO) becomes operational in September, succeeding the Press Complaints Commission, which proved itself incapable of handling a crisis on the scale of phone hacking.

IPSO, it is argued by the industry, will be far more than the complaints-handling organisation that was the PCC. It will have powers to investigate newspapers and apply sanctions. Even critics of this industry-designed initiative, such as the outspoken press reform campaigner Max Mosley, appear to have high hopes that Sir Alan Moses, the Appeal Court judge and first chairman of IPSO, will be a formidable and independent leader of the new body.

Clearly Hacked Off, the press reform lobby group set up at the time of the closure of the News of the World in 2011 and championed by celebrity figures such as Hugh Grant and Steve Coogan, feels it has unfinished business.

The journalist Joan Smith has become the group’s new Executive Director, promising renewed action to compel the newspaper companies to abide by Leveson’s proposals. The industry, in turn, claims that it has taken due account of Leveson in the construction of IPSO. What the judge himself thinks we cannot be sure, as he has steadfastly refused to comment on the response to his recommendations even when questioned on the matter by MPs of the House of Commons media select committee in October. “I have said all I can say on the topic,” he said. “It is for others to decide how to take this forward.”

When the hacking scandal first surfaced in the summer of 2006, things seemed relatively tranquil in the world of press regulation. Sir Christopher Meyer, the former UK ambassador in Washington and chairman of the PCC, was thought to have run a tight enough ship to be considered a worthy candidate to be the next Mayor of London.

A year earlier in 2005, when the News of the World had been named Newspaper of the Year and attracted criticism from rivals for its supposed gutter press methods, the editor Andy Coulson had made a pointed reference to the regulator. “There’s a pretty well-established set of Press Complaints Commission rules, and there’s the law. We know the law, we know the PCC, and we work within it,” he said.

After his royal editor Clive Goodman was charged over hacking in August 2006, Coulson was said to be “relaxed” about his position. After Goodman and private detective Glenn Mulcaire were jailed in February 2007, Meyer wrote to all newspapers to ask what checks they had in place to prevent “intrusive fishing expeditions”. But the PCC decided there was no need for changes to its Code of Practice. In Fleet Street, life pretty much went back to normal.

Video: Cameron's apology for employing Coulson

When the hacking scandal blew up again in 2009, following fresh revelations in The Guardian, the Tory peer Baroness Buscombe had taken over as PCC chairman. A few months later, she gave a speech to the Society Editors rubbishing claims by solicitor Mark Lewis, who represented hacking victims, that Scotland Yard had evidence that the News of the World’s criminality had been on a much grander scale than previously thought. Lewis sued her and, embarrassingly, she was forced to apologise. From then on, as more and more hacking victims emerged, the PCC’s reputation was irrevocably damaged.

Whether IPSO will do a better job remains to be seen. In the eyes of cynics it is merely the latest in a line of self-regulatory bodies – each prompted by outcries over falling standards - that stretches back to the founding of the Press Council in 1953.

But none of the previous regulators have been preceded by the degree of angst and hand-wringing that we have seen in the past three years.

Most observers would say that the tabloids have altered their ways. Certainly there have been no major press scandals in the past three years, unless you count the clash between the Mail and the Labour Party over the paper’s coverage of Ralph Miliband last October.

That there will be another crisis at some point in the future is hardly in doubt. And that’s when we will discover whether, in IPSO, we finally have an effective regulator of the press.