Alexander Litvinenko murder inquiry: The five unanswered questions at the end of the proceedings

Mary Dejevsky explains why the proceedings failed to get to the bottom of the former Russian agent’s death

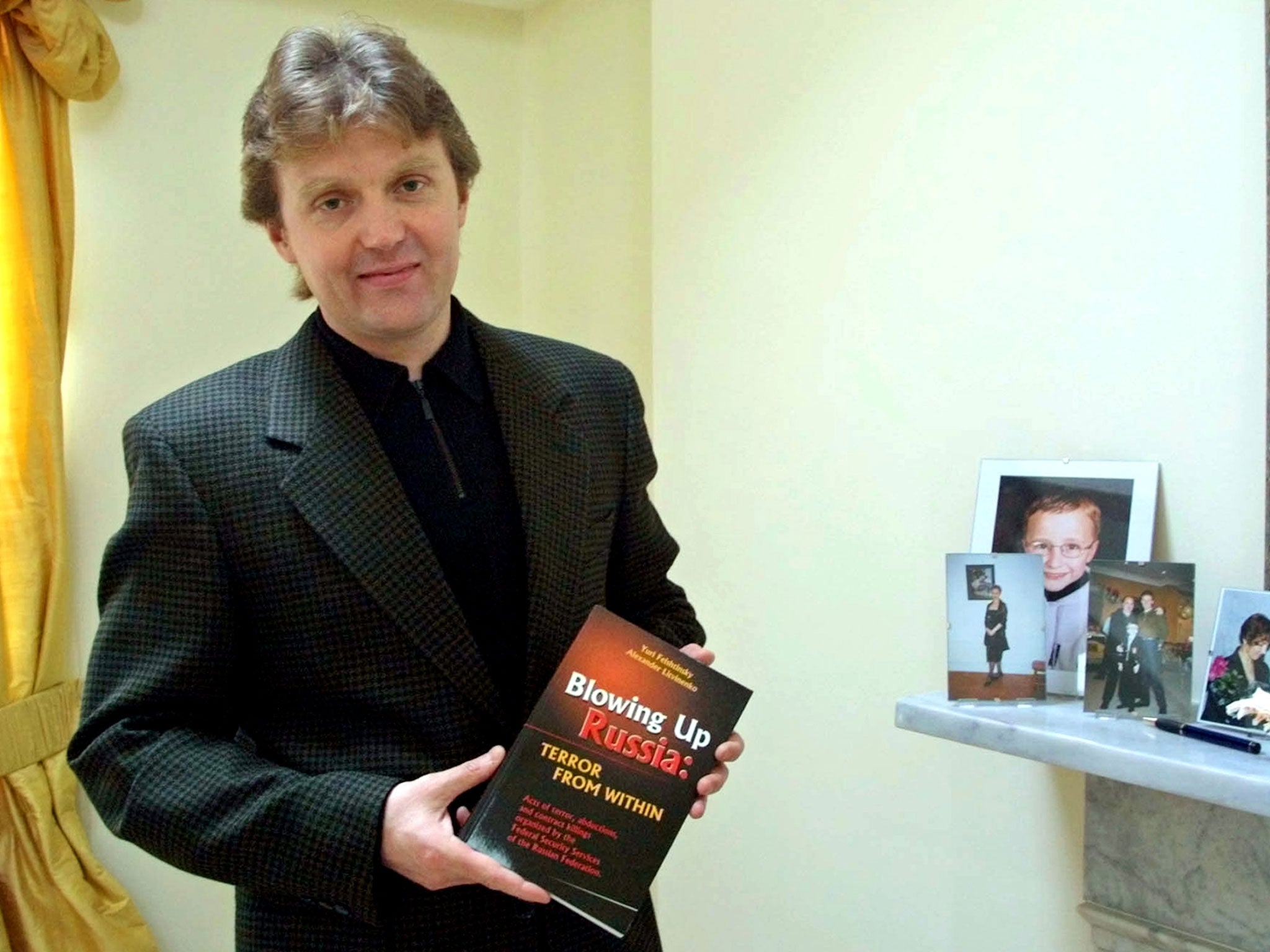

The inquiry into the death of the Russian security officer, Alexander Litvinenko, almost nine years ago concluded in a blizzard of invective from the counsel for his widow, Marina. Ben Emmerson QC, who said the guilt of the two accused, Andrei Lugovoi and Dmitry Kovtun, had been proved beyond all doubt, and the chain of command led all the way to President Vladimir Putin.

He described Mr Putin as “an increasingly isolated tinpot despot” and a “morally deranged authoritarian”, who had been shown to have political and personal reasons for wanting to “liquidate” Mr Litvinenko.

Speaking outside the Royal Courts of Justice after proceedings closed, Ms Litvinenko said she believed the truth had finally been told and her husband’s “murderers and their paymasters... unmasked”. She said: “Any reasonable person who looks at the evidence presented in the inquiry will see my husband was killed by agents of the Russian state in the first-ever act of nuclear terrorism on the streets of London. This could not have happened without knowledge and consent of Mr Putin.”

In his closing remarks, which ended six months of hearings both in public and in strict secrecy to shield, among others, members of the UK security services, the judge, Sir Robert Owen, praised the diligence of the police and the determination and dignity of Ms Litvinenko. He said he would submit his report to the Home Secretary by Christmas, although it is not clear how much, or even whether, it will be published.

What is known?

The post-mortem examination established that Mr Litvinenko died as a result of radioactive poisoning, from a massive dose of polonium 210. As summed up by the counsel for the Metropolitan Police, the evidence against Mr Lugovoi and Mr Kovtun appears incontrovertible. The police case is that there were two attempts to poison Mr Litvinenko, the first on 16 October 2006, and the second – with a much larger dose, the notorious tea in the Pine Bar at the Millennium Hotel in Mayfair – two weeks later. The phone records, the travel records, and above all, the scientific evidence supports their culpability.

The unasked questions

Although an inquiry is supposed to be investigative rather than adversarial, a weakness of the proceedings was the absence of anything that resembled a cross-examination. The police case is that Mr Lugovoi and Mr Kovtun set out to murder Mr Litvinenko with an untraceable poison, polonium-210, but also that they may not have known what poison they were using or the danger it represented to them. This supposedly explains why Mr Lugovoi was happy for his young son to shake Mr Litvinenko’s hand soon after the poisoning. There are other points that might have been contested.

The role of the UK intelligence services

The waiter identified in newspaper reports (courtesy of the police) as having poured the fatal tea testified that he did no such thing.

It emerged that Mr Litvinenko was in the pay of the UK security services, met regularly with his handler “Martin” and travelled on their account in a name other than his assumed UK name, Edwin Carter. It emerged, too, that “Martin” and perhaps other UK agents were at his deathbed. What was the role, if any, of UK and perhaps other intelligence services? What did they know? Mr Lugovoi has said in interviews that MI6 used Litvinenko to try to recruit him. Is this so?

Where does Russia stand?

The Russian authorities were invited to be represented at the inquiry, and, although they co-operated in the early stages, they declined. Mr Lugovoi and Mr Kovtun were invited to be represented and to testify, but refused.

Mr Kovtun – perhaps for his own reasons, perhaps because the Russian authorities saw this as a way of accessing confidential material – made an offer to testify in March, but failed to turn up for the Moscow videolink on the appointed day, citing a host of legal reasons why he had changed his mind. Russia set up its own inquiry soon after Mr Litvinenko’s death; the commission continues, but appears to have produced no results. On On 31 July, Kremlin spokesman said the accusations against Russia were familiar and that Russian officials wanted nothing to do with the British investigation into Mr Litvinenko’s death.

What is the report likely to turn on?

As of now, it appears inevitable that Mr Litvinenko will be found to have been murdered by Mr Lugovoi and Mr Kovtun for political reasons. The big question that Sir Robert will be called upon to answer is whether the killing was masterminded by the Russian security services (FSB), and, if it was, whether it was done on Mr Putin’s orders. Mr Emmerson argued that Mr Litvinenko’s greatest “crime” was to have supplied evidence of Mr Putin’s alleged complicity in organised crime. Opponents of Mr Putin in exile take the same view, and see Mr Litvinenko’s death in the context of other political killings, such as that of the journalist Anna Politkovskaya.

Some witnesses were more circumspect, arguing that the murder could have been the result of a lower-level vendetta. What Sir Robert decides to say about the role of Mr Putin and the Russian state will have implications for UK-Russian relations for a long time.