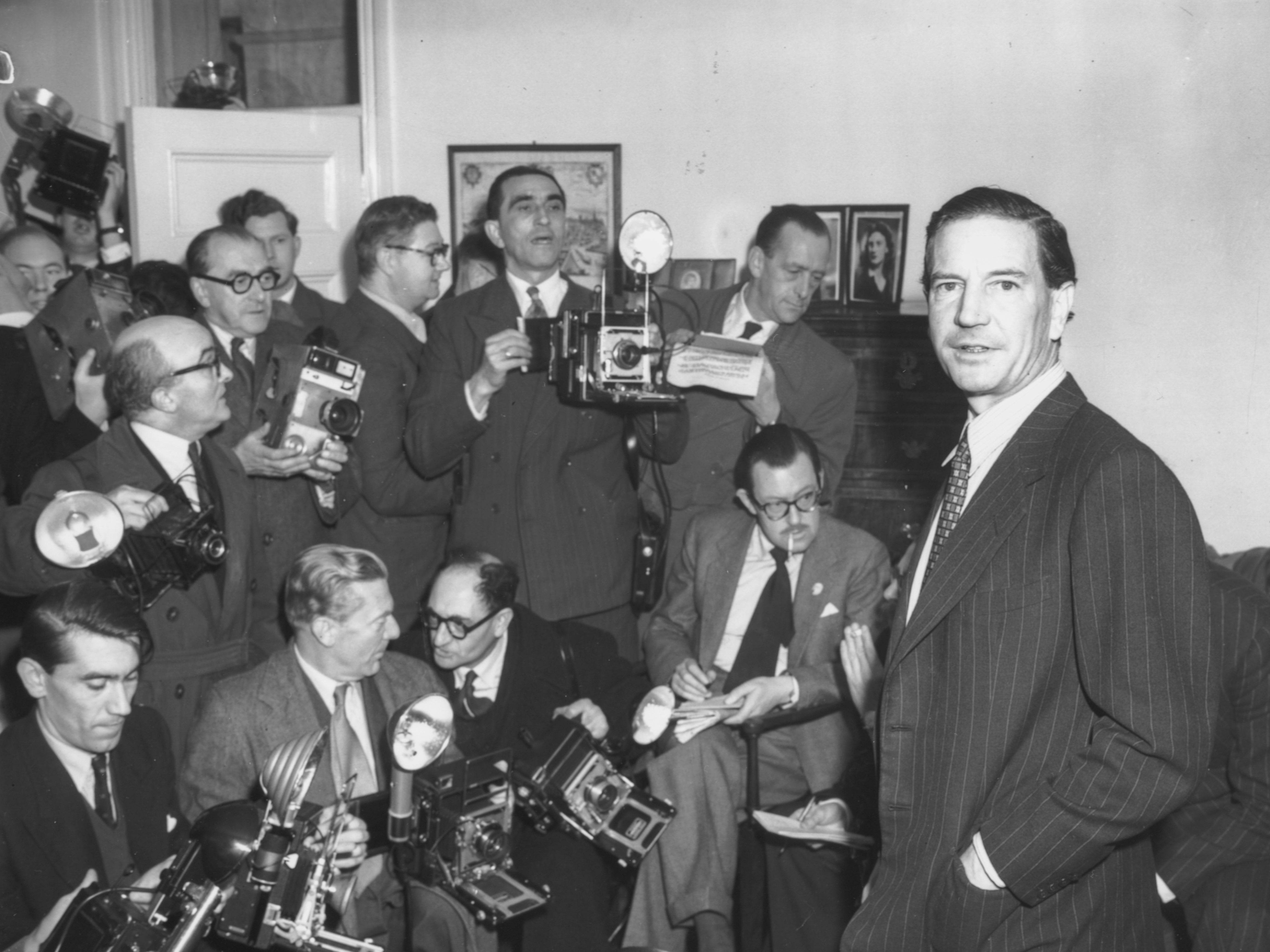

Cold War double agent Kim Philby’s Moscow archive offered to British Library for £68,000

Kim Philby was recruited by Russia in the 1930s and soon rose to become a senior officer in MI6 before coming under suspicion in the 1950s

The British Library attempted to purchase a notorious Cold War double agent’s archive in a deal worth tens of thousands of pounds to his widow, documents have revealed.

Kim Philby was recruited by Russia in the 1930s and soon rose to become a senior officer in MI6 before coming under suspicion in the 1950s.

Cabinet papers unsealed and released by the National Archives in Kew after 30 years have revealed the horror the government felt when they realised a public body could help “enrich a traitor’s widow.” Mr Philby’s treachery as part of the Cambridge Five spy ring was blamed for countless agent deaths.

The library was first approached by Mr Philby’s Russian fourth wife, Rufina, in 1993, five years after his death and 30 years after he fled to Moscow. She wanted £68,000 for the collection which included key details of a course the spy had run following his defection to the Soviet Union for KGB agents preparing to deploy to the UK.

The son of a British diplomat embraced communism while studying at Cambridge in the early 1930s. His influential connections attracted the attention of Soviet spymaster Arnold Deutsch, who advised Mr Philby to sever ties with his communist associates to infiltrate the British establishment.

Posing successfully as a loyal patriot, Mr Philby then joined MI6 during the Second World War and held posts in Istanbul and Washington DC while spying for the Soviets.

As the head of counter-Soviet intelligence, he became a fox in the henhouse, thwarting a Soviet agent’s defection and undermining an Allied operation against communist Albania.

His fellow Cambridge spies, Donald Maclean and Guy Burgess, were exposed in 1951 which led to suspicion turning towards him. But due to a lack of solid evidence, Philby remained free.

It was not until a decade later that a KGB defector confirmed Mr Philby was a Soviet spy. Nicholas Elliott, one of Mr Philby’s closest friends in MI6 who had always believed he was innocent, was assigned to get a confession from him. Elliott told Mr Philby, “I once looked up to you, Kim. My God, how I despise you now.”

It was Michael Borrie, a senior member of the library staff, who contacted the Cabinet Office about the archive deal on behalf of the chief executive saying they were keen to go ahead if suitable arrangements could be made.

He wrote: “The chief executive feels that these should be in a British public institution, provided they are what they purport to be, and have not been sanitised or made a vehicle for disinformation. He is not however willing to spend the grant-in-aid on them, and is looking for a benefactor.”

But a note from one official between the Cabinet Office and the Department of National Heritage, which oversaw the library, said: “I suspect there might be something of a public outcry if it became known that a public was involved even in this indirect way in a traction which would enrich a traitor’s widow.”

Afraid of being imprisoned, Mr Philby fled to Moscow instead of cooperating further. He then lived as a Soviet citizen and national hero until he died in 1988. His granddaughter Charlotte Philby recalled in a recent interview with the Times that on visits to his apartment in Moscow, there were “rifles on the wall.”

Mr Philby’s widow did not lose out despite the Library deal falling through, with the archive material eventually selling for £150,000 by Sotheby’s auction house.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments