AI could tackle ‘avoidable’ heart attack deaths, study finds

The tool also helped improve treatments plans for almost half of patients.

Artificial intelligence (AI) could predict if a person is at risk of having a heart attack up to 10 years in the future, potentially saving thousands of lives, a study has suggested.

It could also improve treatment for almost half of patients, researchers said.

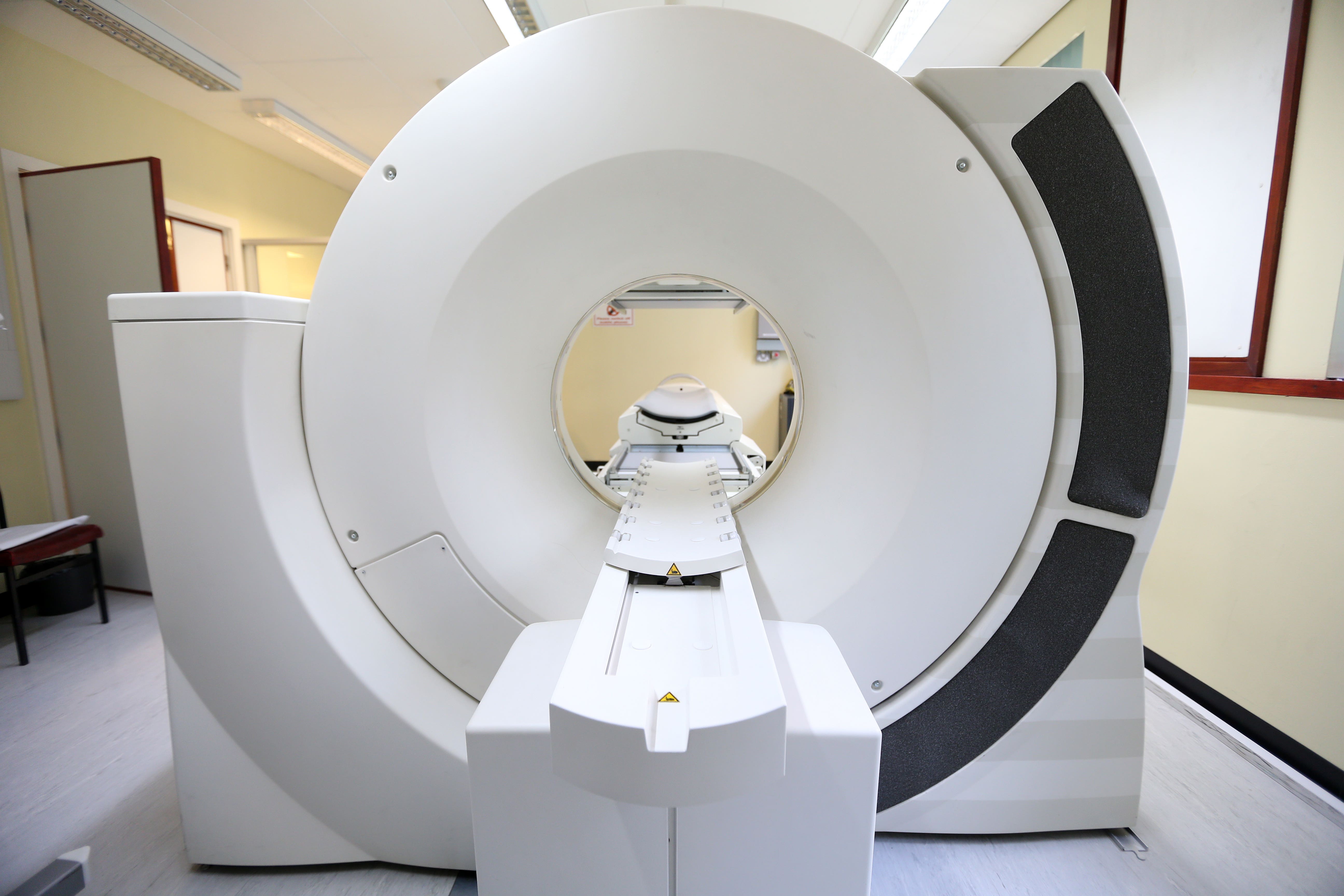

The study by the University of Oxford explored ways to improve the accuracy of cardiac CT scans – which are used to detect any blockages or narrowing in the arteries – using AI.

According to the British Heart Foundation (BHF), which funded the research, about 350,000 people in the UK have one of these scans each year.

Our study found that some patients presenting in hospital with chest pain – who are often reassured and sent back home – are at high risk of having a heart attack in the next decade, even in the absence of any sign of disease in their heart arteries

However, it said many patients go on to die of heart attacks in the future due to their failure in picking up small, undetectable narrowings.

Researchers analysed the data of more than 40,000 patients undergoing routine cardiac CT scans at eight UK hospitals, with a median follow-up time of 2.7 years.

They found those whose results showed “significant” narrowing of the arteries were more likely to have a serious heart attack, but twice as many patients with no significant narrowings also went on to have heart attacks, which were sometimes fatal.

The team developed an AI program that was trained using information on changes in the fat around inflamed arteries, which can signify the risk of a heart attack.

Professor Charalambos Antoniades, chairman of cardiovascular medicine at the BHF and director of the acute multidisciplinary imaging and interventional centre at the University of Oxford, said: “Our study found that some patients presenting in hospital with chest pain – who are often reassured and sent back home – are at high risk of having a heart attack in the next decade, even in the absence of any sign of disease in their heart arteries.

“Here we demonstrated that providing an accurate picture of risk to clinicians can alter, and potentially improve, the course of treatment for many heart patients.”

The AI tool was tested on a further 3,393 patients over almost eight years and found the AI software was able to accurately predict the risk of a heart attack.

AI-generated risk scores were then presented to medics for 744 patients, with 45% having their treatment plans altered by medics as a result.

Prof Antoniades added: “We hope that this AI tool will soon be implemented across the NHS, helping prevent thousands of avoidable deaths from heart attacks every year in the UK.”

Too many people are needlessly dying from heart attacks each year. It is vital we harness the potential of AI to guide patient treatment, as well as ensuring that the NHS is equipped to support its use

Professor Sir Nilesh Samani, medical director at the BHF, said the research “shows the valuable role AI-based technology can play” in identifying those most at risk of future heart attacks.

He added: “Too many people are needlessly dying from heart attacks each year. It is vital we harness the potential of AI to guide patient treatment, as well as ensuring that the NHS is equipped to support its use.

“We hope that this technology will ultimately be rolled out across the NHS, and help to save the lives of thousands each year who may otherwise be left untreated.”

The study was also backed by the National Institute for Health and Care Research Oxford Biomedical Research Centre.

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks