Thousands of students could miss out on university first choices, says professor

The Government has already stated that grades look set to drop this summer, as students transition back to exams in the wake of the pandemic.

Tens of thousands of students could miss out on their first choices for university in what is likely to be the most competitive year ever for courses, it has been suggested.

The proportion of pupils receiving top grades could fall by almost 10 percentage points compared with last year, when students were given grades determined by teachers rather than exams due to the Covid-19 pandemic, an education expert has said.

The Government has already stated that grades look set to drop this summer, and then again in 2023, as part of a transition back to pre-pandemic arrangements.

Professor Alan Smithers, director of the Centre for Education and Employment Research at the University of Buckingham, said there could be 80,000 fewer top grades – A* or A – awarded than in 2021, meaning some 40,000 students could miss out on their course or university of choice.

He has predicted that the 2022 pass rates could see 35.0% of candidates receiving an A* or A grade, compared with 44.8% of entrants last year.

The overall pass rate (grades A* to E) in 2021 was 99.5%, and some 88.5% received a C or above, up from 88.0% in 2020 and the highest since at least 2000.

Prof Smithers suggested that this month will see 82.0% of candidates get an A* to C grade, and 98.5% get an A* to E grade.

In September Ofqual, the exams regulator for England, announced that this year’s grades would aim to reflect a midway point between 2021 and 2019.

Prof Smithers said he can understand why, “since those wanting to go to university will be competing with those holding inflated grades from the boom years who put off going to university during the pandemic”.

He said it is likely there could be 80,000 more A or A* grades than 2019, but 80,000 fewer than in 2021.

The figures could translate to some 40,000 – and even up to 60,000 – students missing out on their first choices, he said.

Describing 2022 as “likely to be the most competitive ever”, he added: “Not only will there be the extra top grades, but there is the carry-over from the Covid years, increased demand from mature and overseas students, and the number of 18-year-olds is rising, nearly half of whom apply to university.

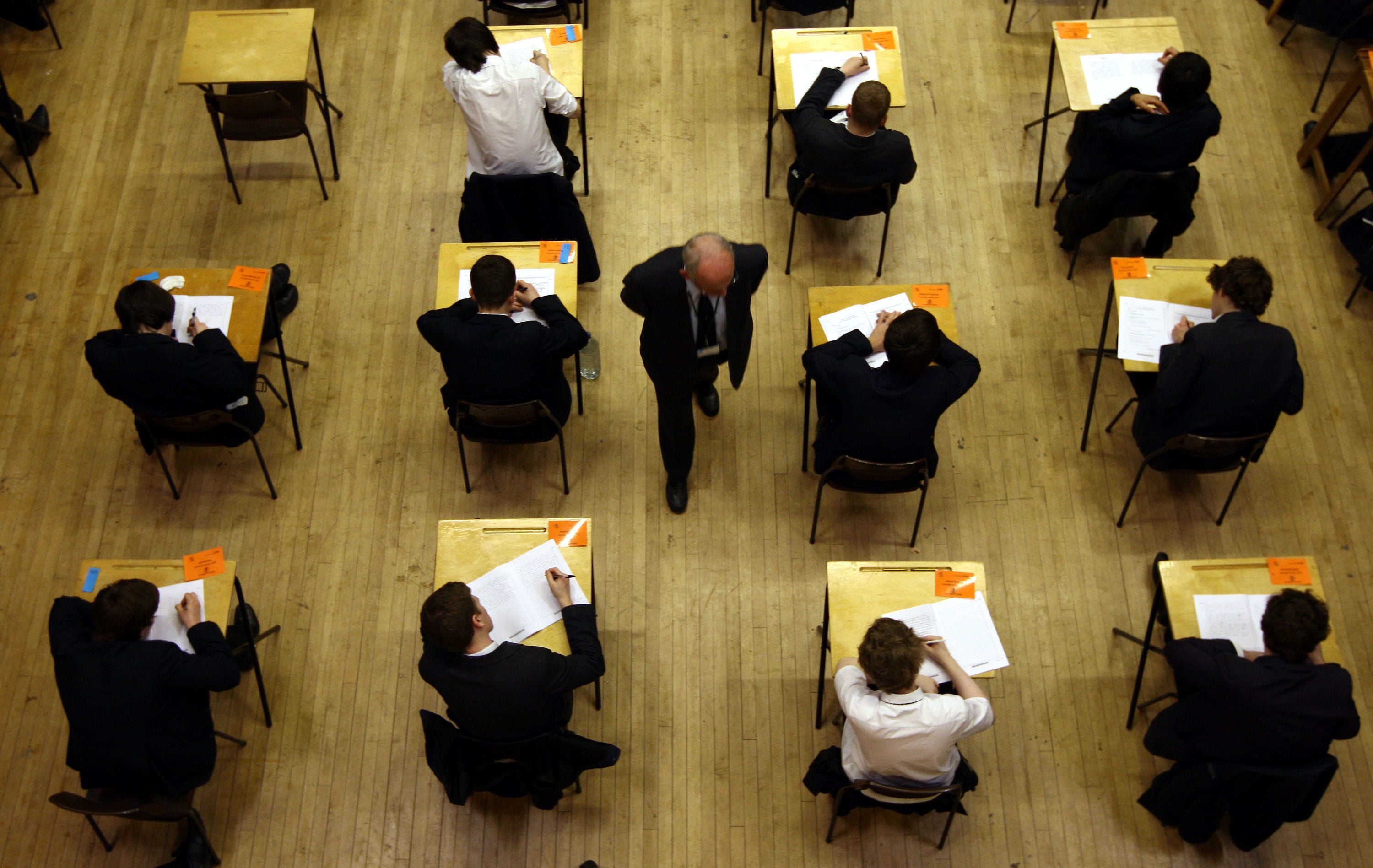

For many of this year’s school leavers the hard work did not end with A-levels, but begins again on results day in the chase for the coveted places

“Universities have reacted to the teacher-assessment boom in top grades by raising requirements and reducing firm offers. For many of this year’s school leavers the hard work did not end with A-levels, but begins again on results day in the chase for the coveted places.

“As a result of bringing down the top grades, about 40,000 applicants could miss out on their first choices, although it could be as many as 60,000.”

He reassured pupils there will be “a place for everyone somewhere since there is no government cap on places, but the top courses will come under heavy pressure”.

He said measures to tackle grade inflation are “part of a process of trying to restore meaning to getting a top grade” but added that it will “cause turbulence this year because at least 40,000 students in my view are going to be affected”.

Students have already been warned to have a plan B in place by education minister Will Quince, who also said that “universities will adjust accordingly” to the overall lower grades.

In June, Ucas’s chief executive Clare Marchant warned that this year will “undoubtedly be more competitive for some courses and providers”, with 49% of teachers having told the admissions service they were less confident their students would get their first choice of university compared with previous years and around two in five teachers expecting their students to use the clearing process.

Prof Smithers has also predicted that the gap between girls and boys’ results will narrow, but said he thinks girls will stay ahead.

He said some of the help given to pupils this year to help them transition back to full exams, such as advance notice of topics, “plays to girls’ strengths”.

The professor also predicted that England’s and Wales’s results will be close, but “still lag appreciably behind those of Northern Ireland”.

A spokesman for exams regulator Ofqual said there is “no link between grades and the supply of places”.

He said: “While there may be fewer top grades this year compared to 2021, when a different method of assessment (teacher-assessed grades) was used, universities understand what grades will look like overall this year and have made offers accordingly.

“According to Ucas, while the number of people deferring last year to this year did increase slightly, it won’t affect the vast majority of courses this year.”

Responding to the report, Ms Marchant said Ucas is predicting a “record, or near record, number of 18-year-olds getting their first choice this year” but added that “as in any year, some students will be disappointed when they receive their grades”.

Sarah Hannafin, senior policy adviser for school leaders’ union NAHT, called on universities to be flexible and work with students “to get them on the right courses and paths for their futures” having taken account of “the disruption this year’s students have experienced”.

A Department for Education spokesman rejected suggestions around deferrals and increased demand from overseas students, saying: “Last year did not see a high number of deferrals compared to previous years and UK students take up the vast majority of places on university undergraduate courses compared to international students, so it is not right to suggest that these factors have caused a squeeze on places.

“Competition for places at the most selective universities has always been high and this year is no different – but there will always be lots of options for students either at another university, through clearing or high-quality vocational options that are just as prestigious and rewarding as academic routes.”

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks