State lawmakers work to strip old 'whites only' covenants

The nation’s reckoning on race has given new momentum to efforts to help U.S. homeowners somehow disassociate their properties with historic, racially restrictive property covenants

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

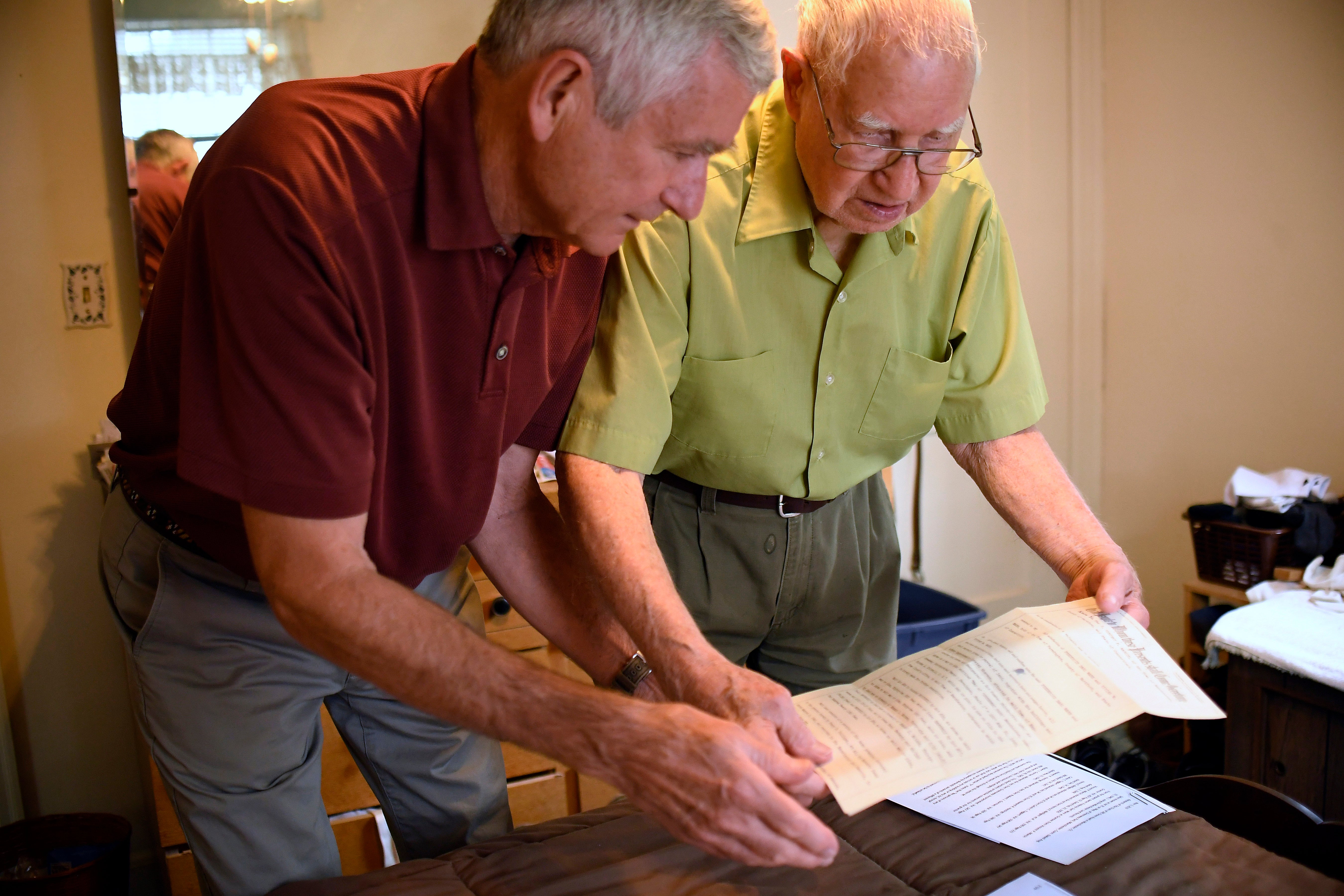

Your support makes all the difference.Fred Ware and his son were researching the history of the home he's owned in the Hartford suburbs since 1950 when they discovered something far uglier than they expected.

Tucked in a list of rules on the home's original deed from the developer was a provision that said: “No persons of any race other than the white race shall use or occupy any building or any lot,” with the exception of “domestic servants of a different race.”

“He was stunned and I was stunned. This is the house I grew up in and is the only home my dad has ever owned,” David Ware said.

While the U.S. Supreme Court in 1948 ruled such racially restrictive housing covenants unenforceable, many remain on paper today and can be difficult to remove. In Connecticut, David Ware asked legislators to help homeowners strike the language, and a bill ultimately was signed into law by Gov. Ned Lamont a Democrat, in July.

The nation's reckoning with racial injustice has given new momentum to efforts to unearth racist property covenants and eradicate the language restricting residency to white people. It also has highlighted the ramifications such restrictions have had on housing segregation and minority home ownership challenges that persist today.

Scot X. Esdaile, president of the Connecticut State Conference of the NAACP, said the law's passage is bittersweet because housing discrimination remains an enduring problem.

"We’re glad that the law is being passed, but the practices are still being carried out today. We see gentrification going on all over America. So housing is a huge issue and this law doesn’t eradicate behavior,” he said.

Ten states this year have passed or are considering bills concerning restrictive covenants based upon race or religion, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. Besides Connecticut, the list includes California, Indiana, Ohio, Utah, Washington Colorado, Nebraska, New York and North Carolina. In 2020, three states — Maryland, New Jersey and Virginia — passed legislation concerning covenants. In some cases, the bills update earlier anti-discrimination laws already on the books.

The restrictive language was written into property documents in communities throughout the U.S. during the early- to mid-20th century amid the Great Migration, which saw millions of African Americans move from the rural South to the urban Northeast, Midwest and West.

These restrictive covenants were a tool used by developers, builders and white homeowners to bar residency by Blacks, Asians and other racial and ethnic minorities. Even after they became unenforceable, according to historians, people privately abided by the covenants well into the 1960s.

David Ware, a corporate attorney, was working on a Master of Laws degree in human rights and social justice in 2019 when he first learned about such covenants. That prompted him and his father Fred, a genealogy buff who is now 95, to go through a deed for the family home from 1942, the year it was built. Both men are white.

“Sure enough, there was this blatant race-based covenant — only white people can use or occupy the property,” said David Ware, who dug further and found 248 properties in the same Connecticut town of Manchester with racially restrictive covenants. The list includes many homes in his father's neighborhood, which, unlike some historically restricted communities in the U.S., has become racially and ethnically diverse over the years.

Under Connecticut's new law, which passed both chambers of the General Assembly unanimously, the unlawfulness of such covenants is codified in state statute and homeowners are allowed to file an affidavit with local clerks identifying any racially restrictive covenant on the property as unenforceable. The clerks must then record it in the land records.

In Washington, under a law that took effect July 25, the University of Washington and Eastern Washington University are tasked with reviewing existing deeds and covenants for unlawful racial or other discriminatory restrictions and then notifying property owners and county auditors. The law also includes a process for striking and removing unlawful provisions from the record.

“Obviously, most homeowners have no idea that these covenants ... actually exist and they’re in their deeds,” Washington state Rep. Javier Valdez, a Democrat from Seattle, said during a floor speech in March. "I think if they knew that these restrictions existed in their documents, even though they’re not enforceable, they would want to do something about it.”

Several bills concerning covenants are currently before the California legislature, which previously passed legislation allowing property owners to address restrictive covenants. One bill would redact “any illegal and offensive exclusionary covenants in the property records” as part of each sale before they reach the buyer.

In Minnesota where thousands of racial covenants have been discovered by a team of historians, activists, geographers and community members, a law was signed in 2019 that allows residents to fill out a form seeking to clarify that the restrictive covenant is ineffective, and subsequently discharge it from the property.

Rep. Jim Davnie, a Democrat from Minneapolis who pushed for the legislation, said even though such covenants no longer have any force of law, residents should have the ability to address the “dated racist stains” on their homes' titles.

Since passage of the law, a group called Just Deeds has provided free legal and title service to help more than 100 homeowners discharge covenants from their properties. A group of neighbors in Minneapolis went so far as to have lawn signs printed that say, “This home renounced its racial covenant.” The Minneapolis Start-Tribune reported that some are planning to support other initiatives to close the home ownership gap between whites and minorities, support reparations legislation and make micro-reparation payments directly to Black residents of Minnesota.

"Renouncing the covenants is really the first step,” neighbor Eric Magnuson told the newspaper.

__

Associated Press Writers Adam Beam in Sacramento, California; Rachel La Corte in Olympia, Washington; and Steve Karnowski in Minneapolis contributed to this report.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments