Seventeen, Lyric, Hammersmith, London, review: The play is bound to trigger raw Proustian memories

A cast of veteran actors take on the role of a group of teenagers who are celebrating the last day of school and the end of exams in Matthew Whittet's 'Seventeen'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.This joyous and sad blast of a play is by the Australian actor/writer, Matthew Whittet. It observes – with a keen eye that never becomes too anthropological in its monitoring and a compassionate solicitude that only occasionally falters into sentimentality – a group of 17-year-olds as they celebrate the end of exams by dancing with abandon in the local park, getting wasted (at least by their fledgling standards) on tequila and waiting for the sun to rise together.

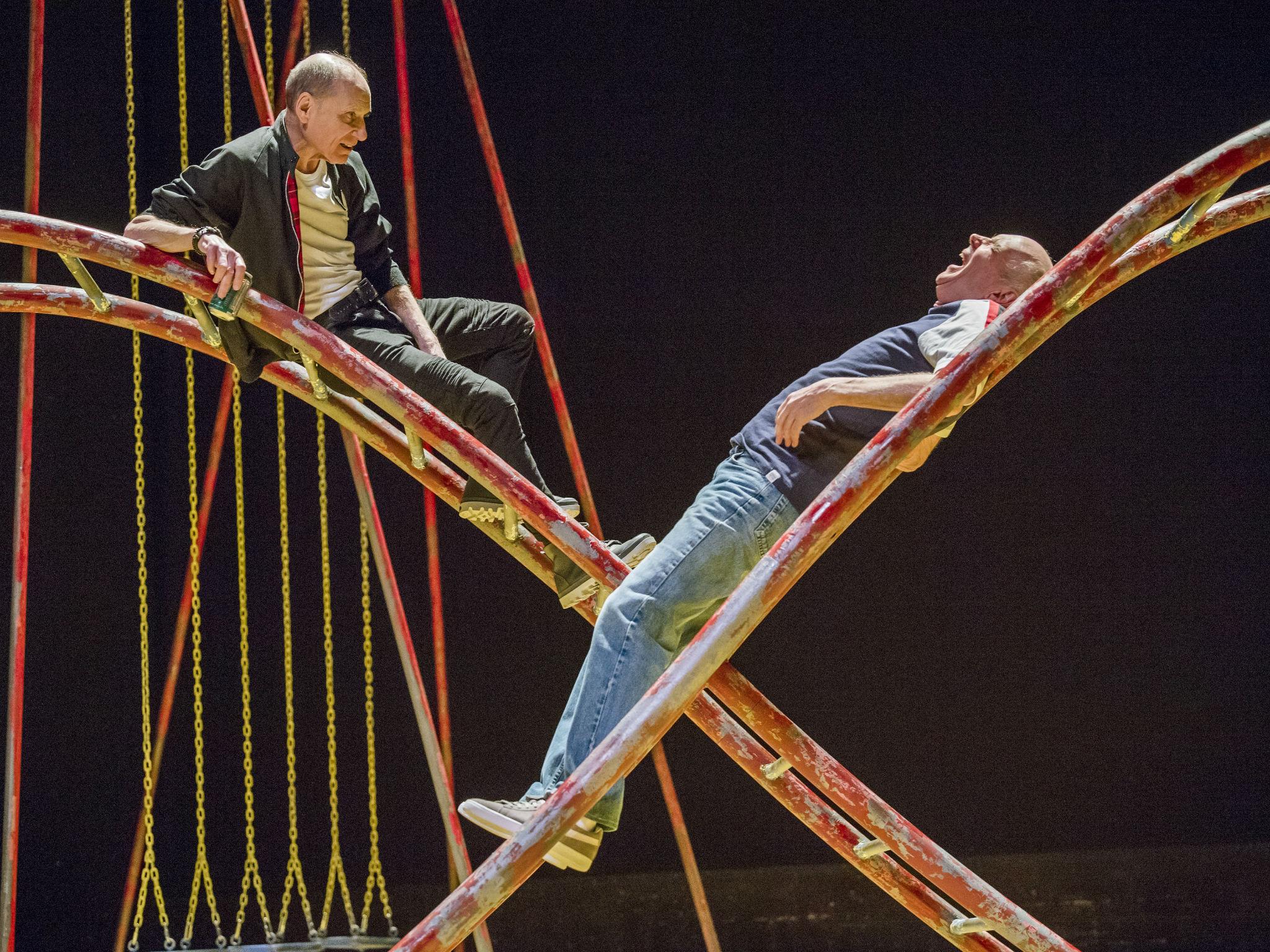

Reader, even I have been there. We all have muscle memories of being released from academic prison: draping our bodies over the bars of a climbing frame and arching our pimpled torsos to the sun, looking more like a display case of Salvador Dali's melting clocks than a bunch of trainee dissolutes. The school's-out-forever fever is gradually infiltrated by a shivery sense that that final bell may never sound until all the rest of your life is over (I'm ashamed to admit how many exam nightmares I still have, speaking as someone who'll be surprised to see, erm, 38 again).

These considerations are built into the warp and weft of the play that stipulates that these adolescents should be played by actors who have been round the block a few times and, as it were, bang into themselves coming back, feeling out this elusive fore-and-aft territory – just as in the piece the teenagers, with much horseplay, read out the shy-making, naive yet lovely time-capsule letters they wrote to their future selves. For my money, this technique is deployed in a more interesting and fugitive way here than it is in the classic Blue Remembered Hills by Dennis Potter to which it is very grateful for its concept.

Watching Anne-Louise Sarks’ excellently cast production (the company is comprised of Brits), I knew I was going have a grand time from the opening dialogue that gives us a picture of these adolescents' lives through their own sharp, hilarious disaffection with it. In fact, just how disaffected hasn't caught up with them yet in certain regards. “I wrote about the parallels between The Tempest and euthanasia” is unimprovable in the glancing speed with which it satirises “relevance” and makes you feel sorry for the teachers, too, caught in its toils.

The aim in neither the dialogue nor the performances is clingfilmed verisimilitude. Accordingly, it makes the play's stark-and-subtle perception of the inequalities than can fester – and flower – in these intense early friendships more true to life because there was no standard of comparison to start with. Michael Feast as Mike is very good at communicating the jivey cockiness whose sell-by date you sense is already kicking in. He's an ace actor of Pinter, among others, and the insecurities seep like teenage BO through the cracks in the over-determined carapace of swagger. It's heartbreaking that his depressed sidekick Tom (spot on) still carries a torch for that conception of manliness, while harbouring his own alternative desires.

Diana Hardcastle is perfection as Jess, the girl with a difficult mother who craves a dependable friendship as is Margot Leicester as Emilia, the better-class girl who, for various reasons, can't quite give this to her. Backstories, set up very lightly, recede into darkness. I could show you fear in the suspiciously full rucksack of the uninvited Ronnie (very well played by Mike Grady). The whole thing is very well plotted. Just right that he is the one to observe a kiss that sends slates flying from this precarious communal edifice. “Shades of the prison house begin to close/Upon the growing Boy” wrote Wordsworth about one stage of transition. Paule Constable beautiful lighting gives us the westering quality, with streaks of hope, that is the compromise position at the end here.

The play is bound to trigger raw Proustian memories. Take the fireman's hose of recollection that it unleashes on me. A boy who was an object lesson in how you could be minimus with no siblings whatsoever, I organised school's-out games for the swots that involved packets of “Love Hearts” and the first scene of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead. The object was to flick the sweets in the air; catch them in your mouth; and guess what the message was. The inventor of said pastime was its worst practitioner and I ended up having to consume two whole packets of the sugary horrors over the course of that golden afternoon in front of a giddy throng.

But I learned some valuable life lessons from the experience. Above all, never to serve this particular confectionery as an amuse-bouche. Indeed, it made the precise identity of the substances I found myself ingesting later in a Chinese restaurant with chums a bit of a puzzle. Sadly, I have never been able to eat more than three of the blighters on the trot since.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments