'World's oldest images made from pixels' discovered in prehistoric French camp

The 38,000-year-old engravings found in the Vézère Valley could be the oldest pictures of any kind in the world, depending on the dating of others

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.What could be the oldest images in the world have been discovered in France.

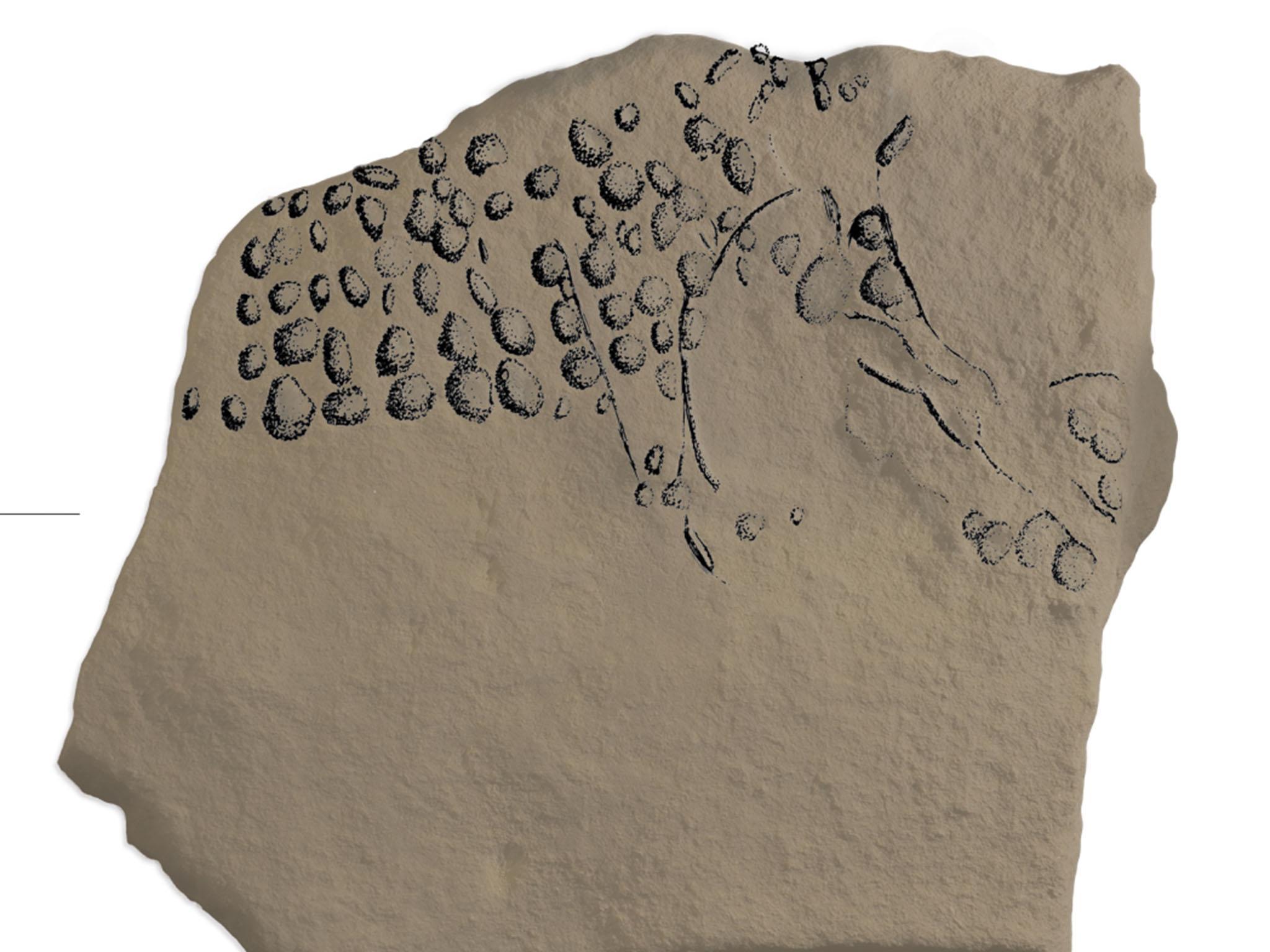

And the engravings of mammoths and wild cows known as aurochs were made from individual pixels – essentially the same technique used to produce images on computers and televisions.

The pictures are also being compared to the pointillism technique supposedly pioneered in the 1880s by artists like Vincent van Gogh and Georges Seurat.

The 16 decorated stone blocks were discovered during an excavation of a now-collapsed rock overhang in France’s Vézère Valley, which was used as a shelter by the Aurignacian people, the earliest modern human culture in Europe.

They were radiocarbon dated to 38,000 years old, which could mean they are the oldest pictures ever created.

A painted hand silhouette found in Spain could be about 5,000 years older but its dating has been contested. An ivory sculpture of a female figure from about the same period as the French engravings was also found in southern Germany.

Professor Randall White, a New York University anthropologist, told The Independent the images were certainly “among the very earliest images of things we can actually recognise in the entire archaeological record”.

The pictures are fairly basic.

But Professor White said it was “after all 38,000 years old and the tools that are being used are rather robust”.

“It’s not so much the final effect that we found interesting, it’s the conception of it – the use of individual points to form the body or the outline of a figure,” he said.

“If you look carefully at the aurochs, there’s really a significant control of the line.

“And this is very early when people are really just beginning to grapple with the production of images.

“They have mastered some of the fundamental aspects of line and shape, but there’s clearly a long way to go in terms of precise reproductions.”

It is unclear why prehistoric artists decided to use a pointillist or pixel-based technique.

“It’s almost digital in its nature … why this fixation on dots, I’ll admit it’s a puzzle,” Professor White said.

“It’s not exactly pointillism but the principle is there, the construction of a form out of pixels.

“We’re quite familiar with the techniques of these modern artists. But now we can confirm this form of image-making was already being practiced by Europe’s earliest human culture, the Aurignacian.”

He said they had been excavating the site for 18 months before they found the images.

“The engraving was face down and we knew within these sites such things are possible, so we were taking great care,” Professor White said.

“After a year and a half of excavating, we finally extracted the object … it is one of the great moments of my career, that’s for sure.”

The discovery was reported in the journal Quarternary International.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments