What being bilingual does to your brain

Researchers say their study of babies shows that early childhood is the 'optimum time' to learn languages

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The difference between the brains of bilingual and monolingual children can be seen as early as 11 months of age, a study has found.

Bilingual children showed more activity in areas of the brain related to 'executive function', which governs tasks such as problem-solving or shifting attention.

"Our results suggest that before they even start talking, babies raised in bilingual households are getting practice at tasks related to executive function," said Naja Ferjan Ramírez, the lead author of a paper about the study.

"This suggests that bilingualism shapes not only language development, but also cognitive development more generally."

In research published in the journal Developmental Science, researchers used an MEG machine to measure the magnetic fields produced by electrical currents in nerve cells in the brains of babies.

The study used 16 11-month-old babies, eight from English-only households and 8 from Spanish-English bilingual households.

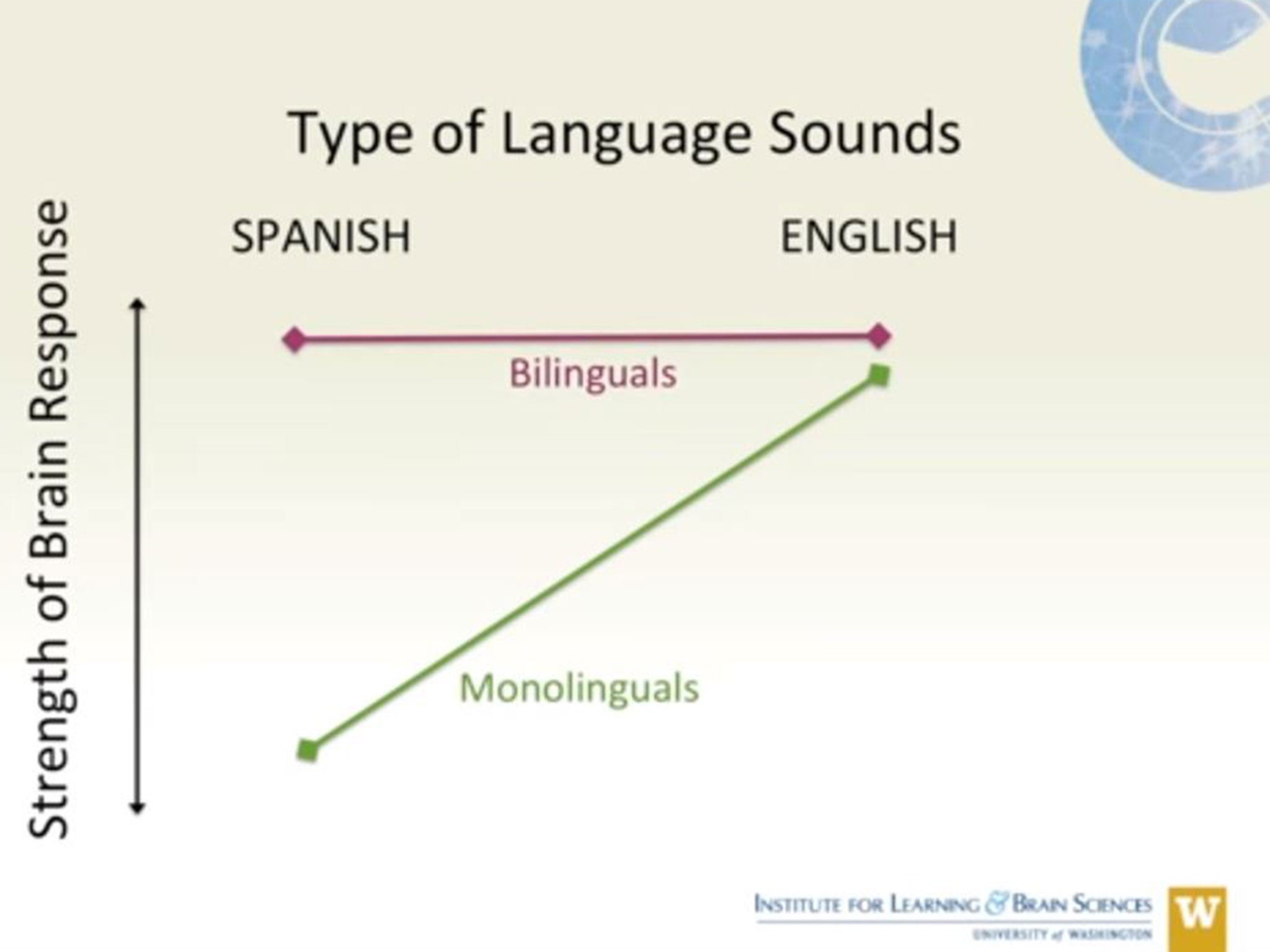

They listened to an 18-minute stream of speech sounds - such as "da's" and "ta's" - which included sounds specific to English or Spanish.

When comparing the brain responses between monolingual and bilingual babies, the researchers saw an obvious difference in the brain regions associated with executive function.

In both the prefrontal cortex and orbitofrontal cortex, Spanish-English babies had stronger brain responses to speech sounds.

The boost given to parts of the brain that deal with executive function could be the result of bilinguals switching back and forth between languages, allowing them to practice and improve executive function skills.

"The 11-month-old baby brain is learning whatever language or languages are present in the environment and is equally capable of learning two languages as it is of learning one language," Ms Ferjan Ramírez said.

"Our results underscore the notion that not only are very young children capable of learning multiple languages, but that early childhood is the optimum time for them to begin."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments