'Voice transplants' one step closer after scientists grow human vocal chords

'Voice is a pretty amazing thing, yet we don’t give it much thought until something goes wrong'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Human vocal cords have been grown in the laboratory for the first time in a development that could one day lead to “voice” transplants for people who cannot speak because of a permanently damaged larynx.

Scientists said that the bioengineered vocal cords grown from individual cells produced sounds similar to those made by the human voice box when warm, moist air was passed over them to make them vibrate.

The researchers believe that it may be possible to generate a variety of synthetic vocal cords which can be used “off the shelf” for transplant operations to suit the individual needs of different patients who cannot speak.

At present there are limited treatment options available for people with a larynx damaged by cancer or other disorders because of the highly specialised nature of the vibrating cells of the vocal cords.

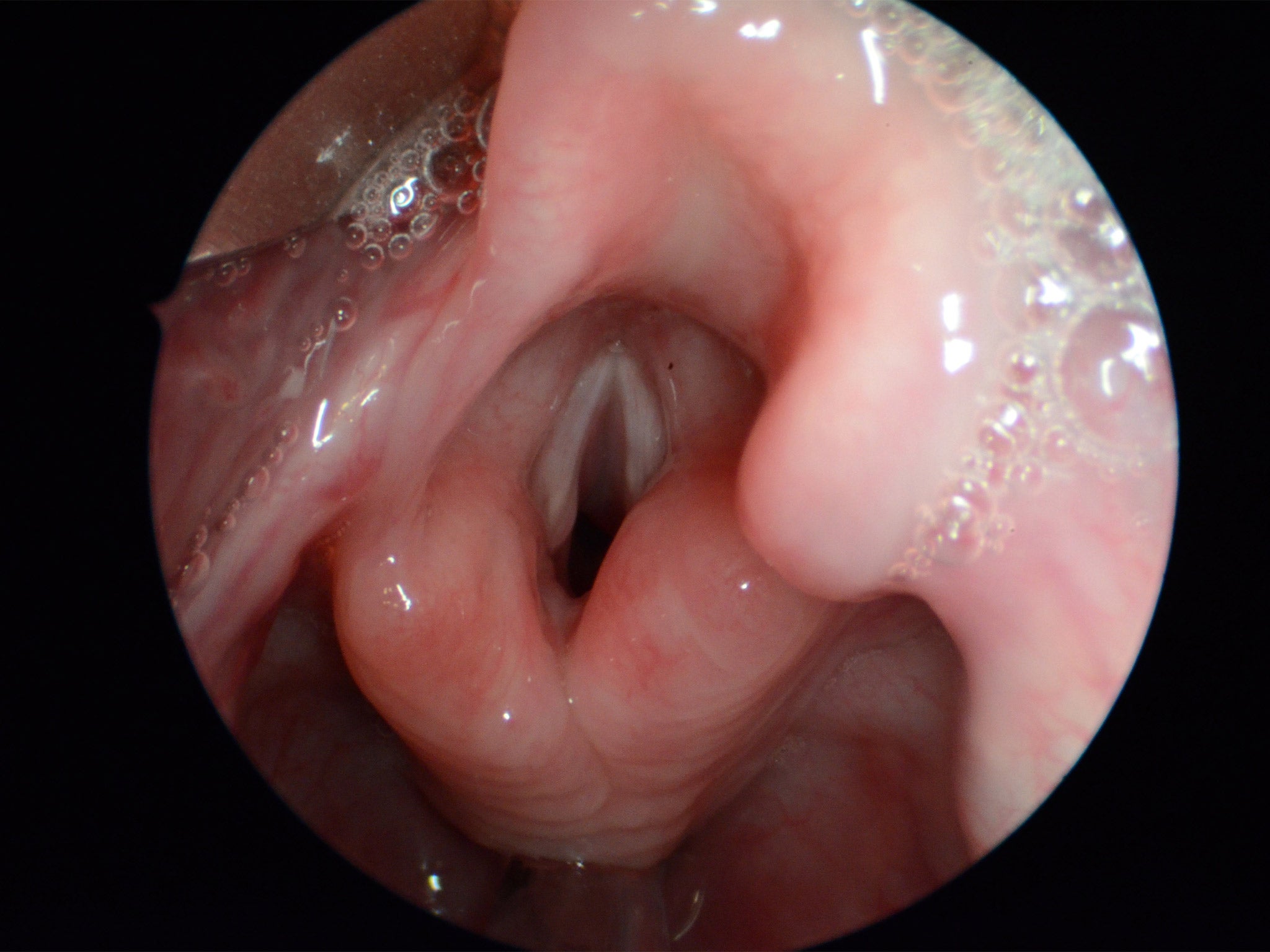

Speech is generated by passing air over the vocal folds – commonly called vocal cords – within the larynx. The folds consist of two flexible bands of muscle lined with delicate, moist tissue called mucosa that vibrate hundreds of times per second to produce sound – much like the vibrating strings of a violin.

The scientists recreated the mucosal tissue of the vocal cords using healthy cells taken from patients who had had their larynxes removed for unrelated reasons, as well as from a human cadaver.

These cells were cultured in the laboratory for about 14 days when they grew around a bio-engineered “scaffold” to mimic the three-dimensional structure of the mucosal lining within human vocal cords.

The two types of cells used in the procedure – fibroblasts and epithelium cells – assembled themselves naturally into different layers just like they do within human vocal cords, the scientists found.

To test whether these synthetic vocal cords functioned normally, the scientists transplanted them into larynxes removed from dead dogs. They then blew warm, moist air through them to compare the sounds they made to those made by natural vocal cords.

In a study published in the journal Science Translational Medicine, the researchers report that the sounds produced by the synthetic vocal cords were similar to those made naturally – although without the additional modulation produced by the throat, mouth and tongue.

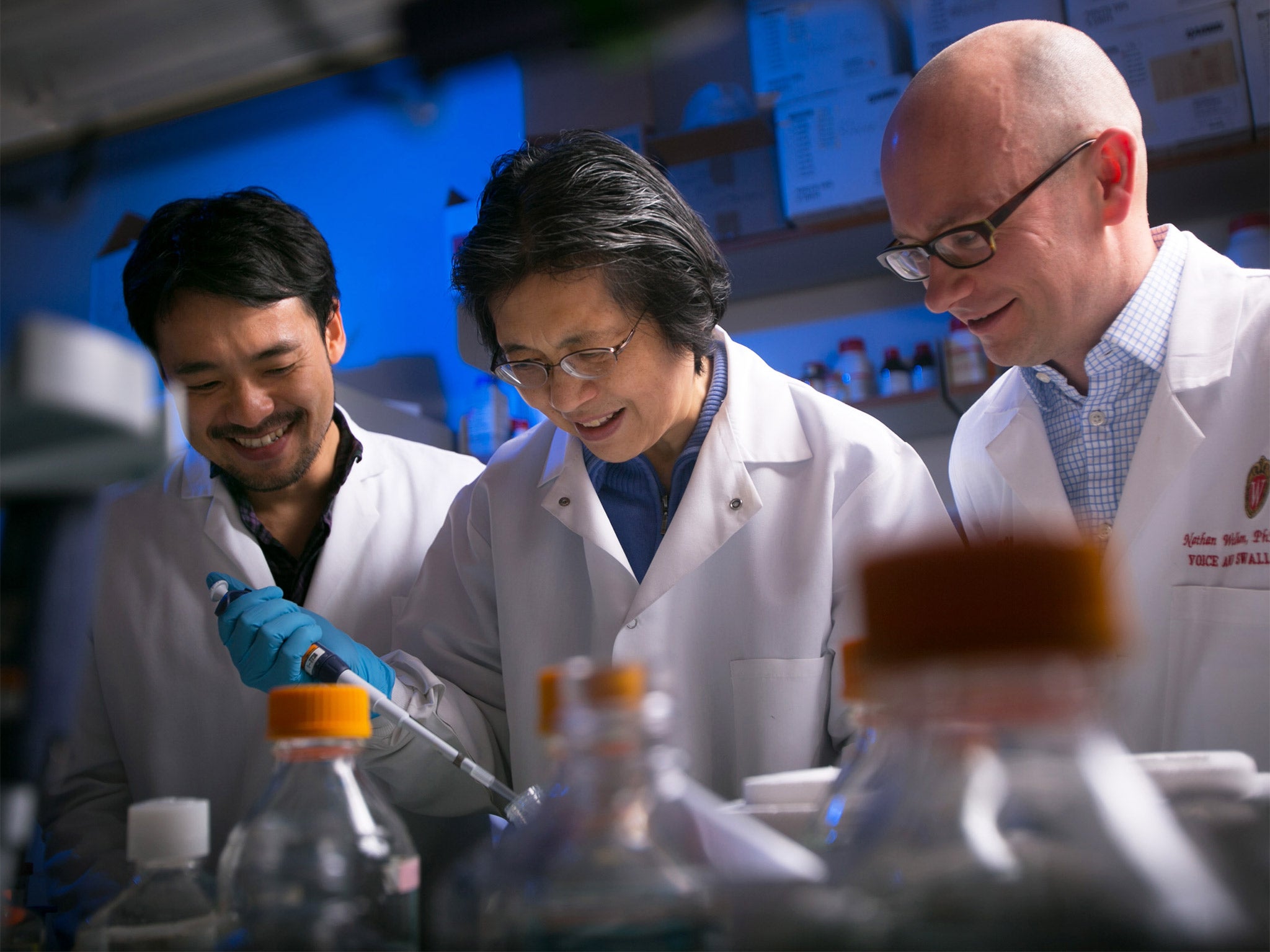

“Voice is a pretty amazing thing, yet we don’t give it much thought until something goes wrong,” said Nathan Welham of the University of Wisconsin-Madison who was one of the leaders of the research project.

“Our vocal cords are made up of special tissue that has to be flexible enough to vibrate, yet strong enough to bang together hundreds of times per second. It’s an exquisite system and hard thing to replicate,” Dr Welham said.

The scientists also transplanted small samples of the synthetic human vocal cord into mice and found that they were not rejected by the immune system, raising hopes that they could one day be used in transplant operations.

“Part of the advantage of using an engineered tissue is that we can customize the size and make the tissue to fit the defect, and also fit the size of the vocal fold in the male or female or child that would be the recipient,” Dr Welham said.

“If we are able to store these or have them ready for off-the-shelf therapy, then they're much more readily available perhaps than trying to match donor and recipient and timing things as is done for solid organ transplantation,” he said.

The researchers warned however that there is still further research to be done before they would attempt a clinical trial on human patients.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments