New images reveal what the weather is like on Uranus and Neptune

The Hubble Space Telescope has spotted clouds and storms on the solar system’s ice giants. Gareth Dorrian and Ian Whittaker report

The outer region of the solar system may be the least explored, but scientists have managed to unravel several of its mysteries in recent weeks.

On New Year’s Day, the Nasa spacecraft New Horizons encountered the icy object Ultima Thule for the first time, shedding light on how it formed.

Astronomers have also just discovered a previously unknown moon orbiting Neptune, which has been dubbed “Hippocamp”.

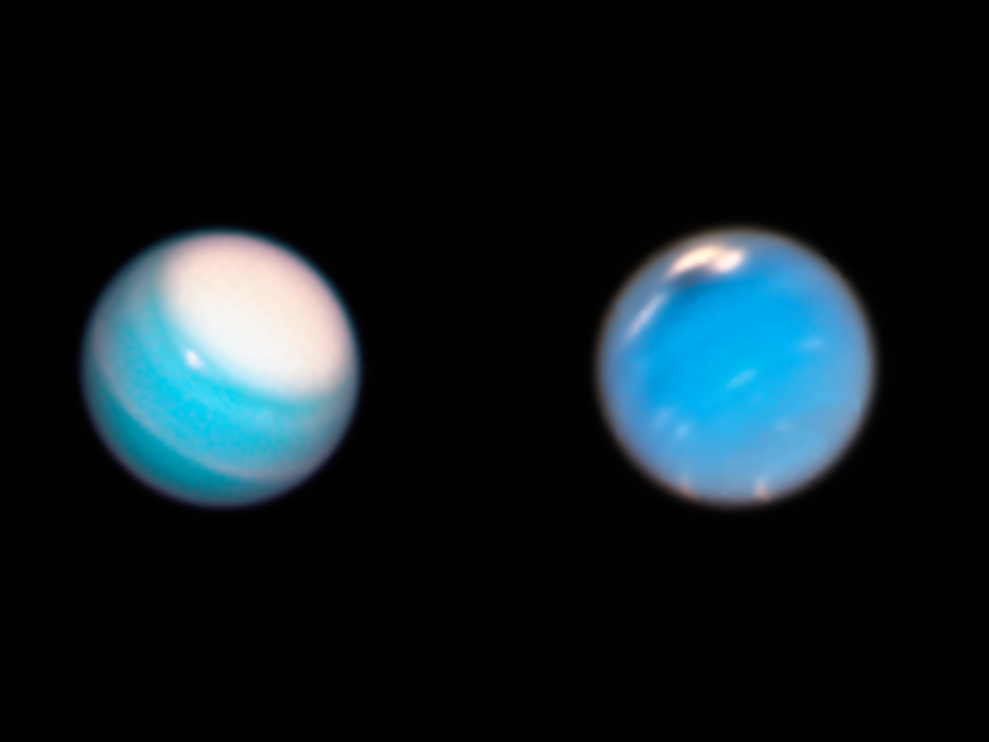

Another discovery, thanks to new images from the Hubble Space Telescope, is that there’s a variety of intriguing weather patterns in the atmospheres of both Neptune and Uranus. So what would it be like to go there?

Having four times the diameter of the Earth, we typically refer to Uranus and Neptune as “ice giants”.

Unlike the gas giants, Saturn and Jupiter, Neptune and Uranus are lower in hydrogen and helium and higher in concentrations of heavier materials such as methane, water and ammonia.

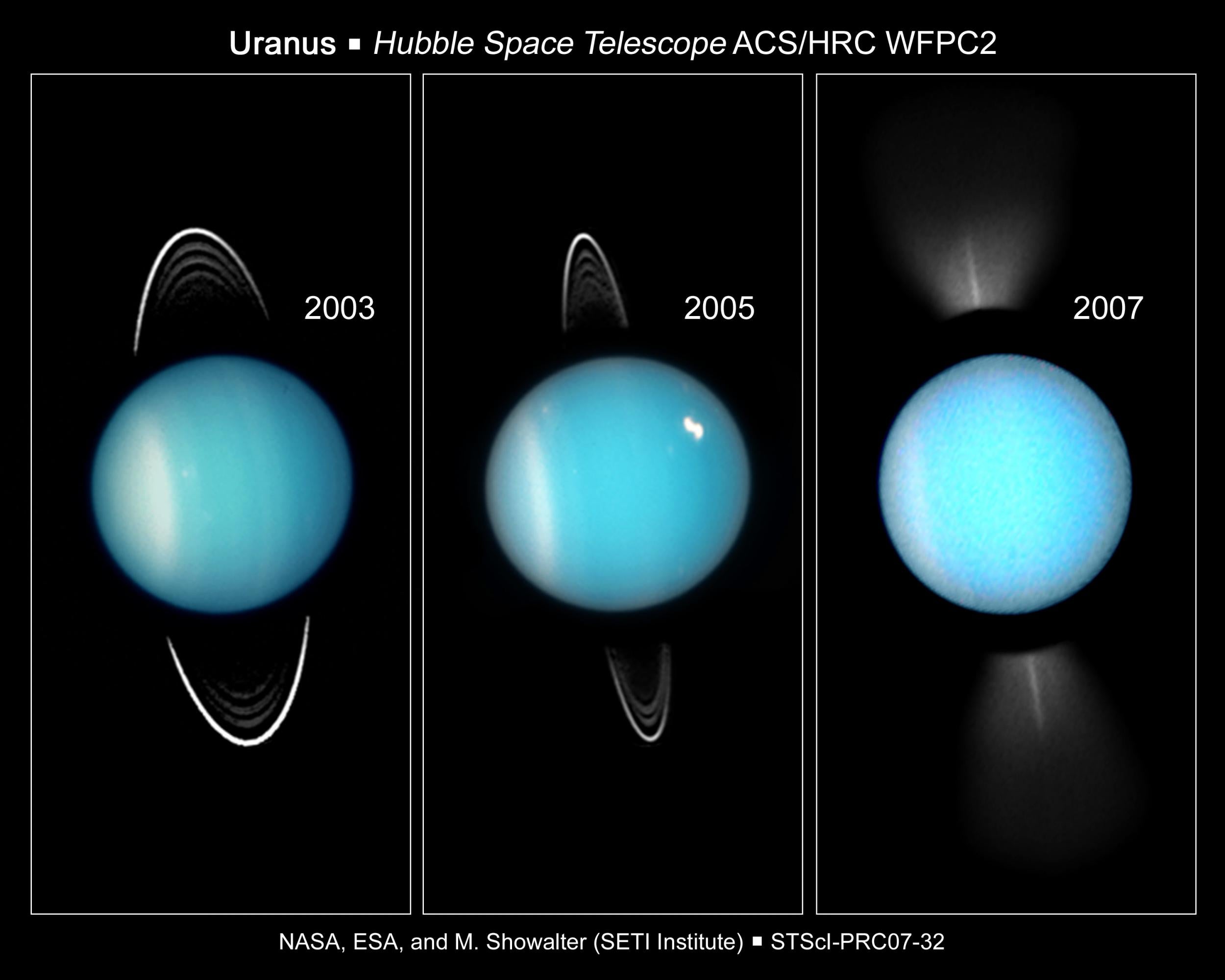

Uranus is especially interesting as it is also the only planet in the solar system that rotates on its side. A northern summer on Uranus lasts 21 years with the north pole receiving constant sunlight, while the south pole sees continual darkness.

This tilt to the Uranian axis is believed to be the result of an early solar system collision with an object at least as large as the Earth.

Such a collision would either have released the internal heat reserves of the planet or created a layer of particles that effectively insulate the interior of the planet – preventing heat flow to space.

Neptune, having avoided such an encounter, still has an outward heat flow. As such, both planets are almost the same temperature (within a few degrees) despite Uranus being 33 per cent closer to the sun.

Weather on Uranus

The absence of any significant internal heat flow on Uranus means that this planet’s atmosphere is distinctly less active than Neptune’s. In fact, the Uranian atmosphere in winter is the coldest planetary atmosphere in the solar system.

When Voyager 2 flew past Uranus in 1986, the planet appeared as a largely featureless green-blue disc. In the years since, however, scientists have realised that even this apparently cold, dead world has a surprisingly dynamic atmosphere.

But the new images from the Hubble Space Telescope show a previously unseen huge white cloud likely composed of ammonia or methane ice enveloping the north pole (see top image).

Clearly visible at the edge of this huge cloud system is a smaller cloud of methane ice that rotates around the larger cloud edge. These cloud structures may be seasonal, resulting from the current constant sunlight at the north pole.

Around the equator of Uranus we can also see a thin band of cloud (top image), though how this cloud band remains so narrow is not currently understood. Wind speeds on Uranus are so high that they can blow clouds along at up to 560mph, which would spread clouds outwards over a large area.

All planetary atmospheres possess a latitudinal circulation system that should, in theory, also distribute this cloud band over wider latitudes. It could be that these methane clouds are somehow constrained by these circulation patterns, due to altitude or chemical instability.

If we could visit Uranus, the winds at a depth equivalent to the atmospheric pressure of Earth’s surface could reach up to 250 metres per second, or roughly three times as fast as a category five hurricane. Be sure to bring your coat, too, as temperatures at this depth are a frigid -200C.

Weather on Neptune

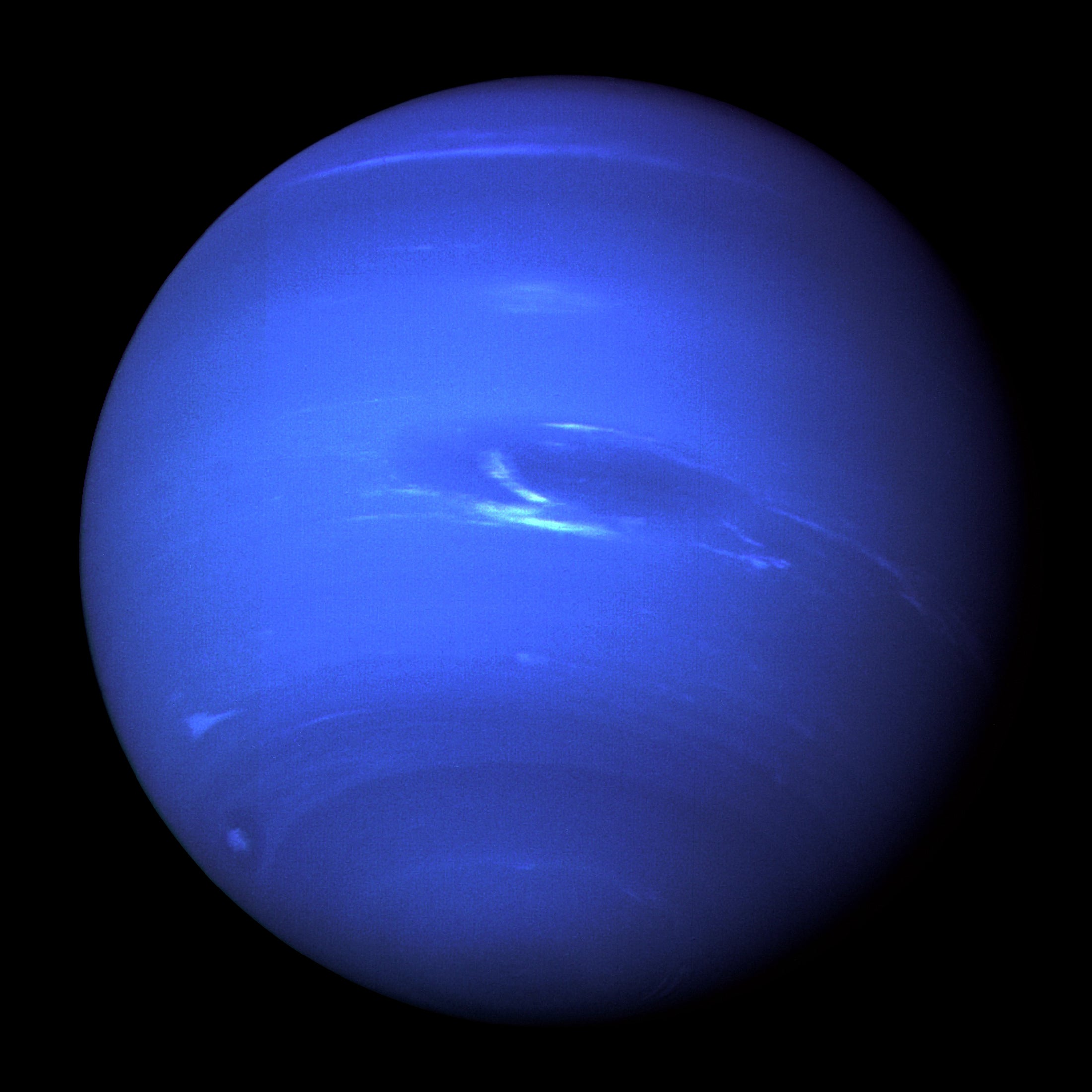

As strong as the winds of Uranus are, they are nothing compared to those found on the other ice giant. Neptune boasts supersonic wind speeds of over 1,300mph, and numerous storm systems.

The most famous of these features was the Great Dark Spot that was observed in close up by Voyager 2 in 1989. This huge storm system covered an area roughly equivalent to one sixth of the surface area of Earth.

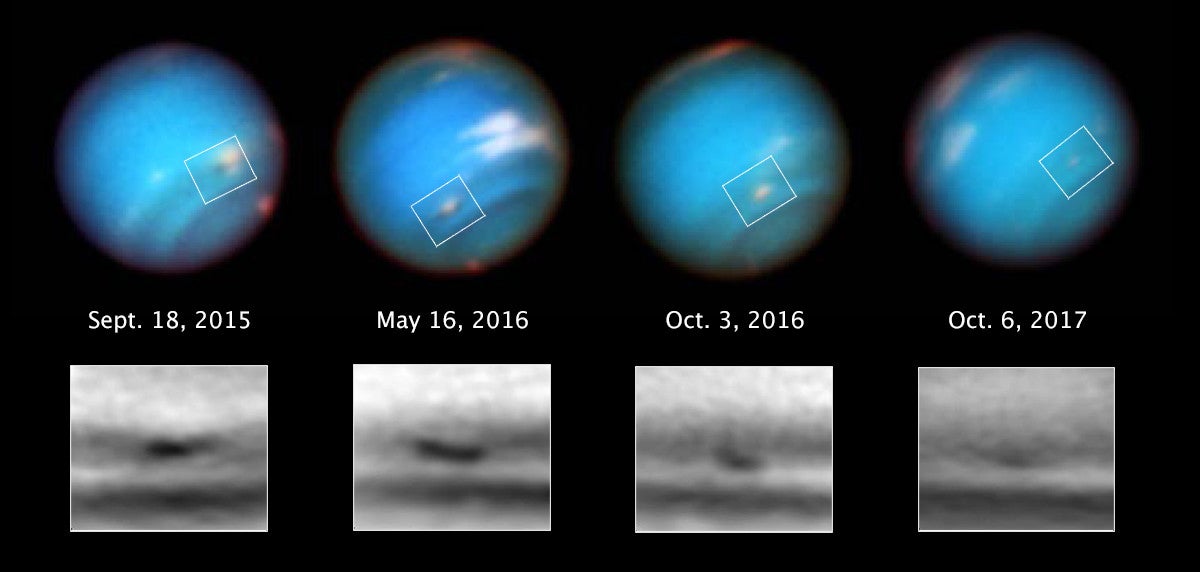

In the latest Hubble images, a different storm system is visible near the North pole, accompanied by bright clouds of methane ice crystals.

The reason these features appear darker than their surroundings is because they are holes offering a view into deeper layers of the Neptunian atmosphere, much like the eye of a hurricane on Earth allows you to see the surface from space.

Like on Jupiter and Saturn, these gigantic storm systems are believed to be powered by heat flowing out of the planet, left over from the planet’s birth some 4.5 billion years ago.

Once again, a visit here would be problematic, with similar temperatures to Uranus but double the wind speed. In fact, Neptune is the windiest planet in the solar system.

The ice giants are the most commonly observed type of “exoplanet” – planets orbiting stars other than our sun. If we know more about Uranus and Neptune, we can therefore understand more about planets throughout the universe.

Of course, the ideal plan would be to travel to these worlds. Sadly, apart from the great distance involved, the exceptionally cold temperatures, massive storms and strong winds make them particularly unsuitable for a human visit.

So for now, we shall just have to rely on telescopes like Hubble to tell us about our local ice giants.

ost doctoral research associate in space science, and Ian Whittaker is a lecturer, both at Nottingham Trent University. This article first appeared on The Conversation

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks