Trump's war on science: could the Canadian experience offer a blueprint on how to fight back?

For a decade, Canadian scientists battled a sinister federal campaign to control and silence them. Now that the US has an even more extreme anti-science leader, veterans of that conflict tell Chantal Da Silva that their southern counterparts must resist early and loudly

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When Canadian biologist Scott Findlay embarked upon a career in science, he never imagined he would one day find himself marching up the steps of Ottawa’s Parliament Hill, carrying a casket filled with scientific research papers.

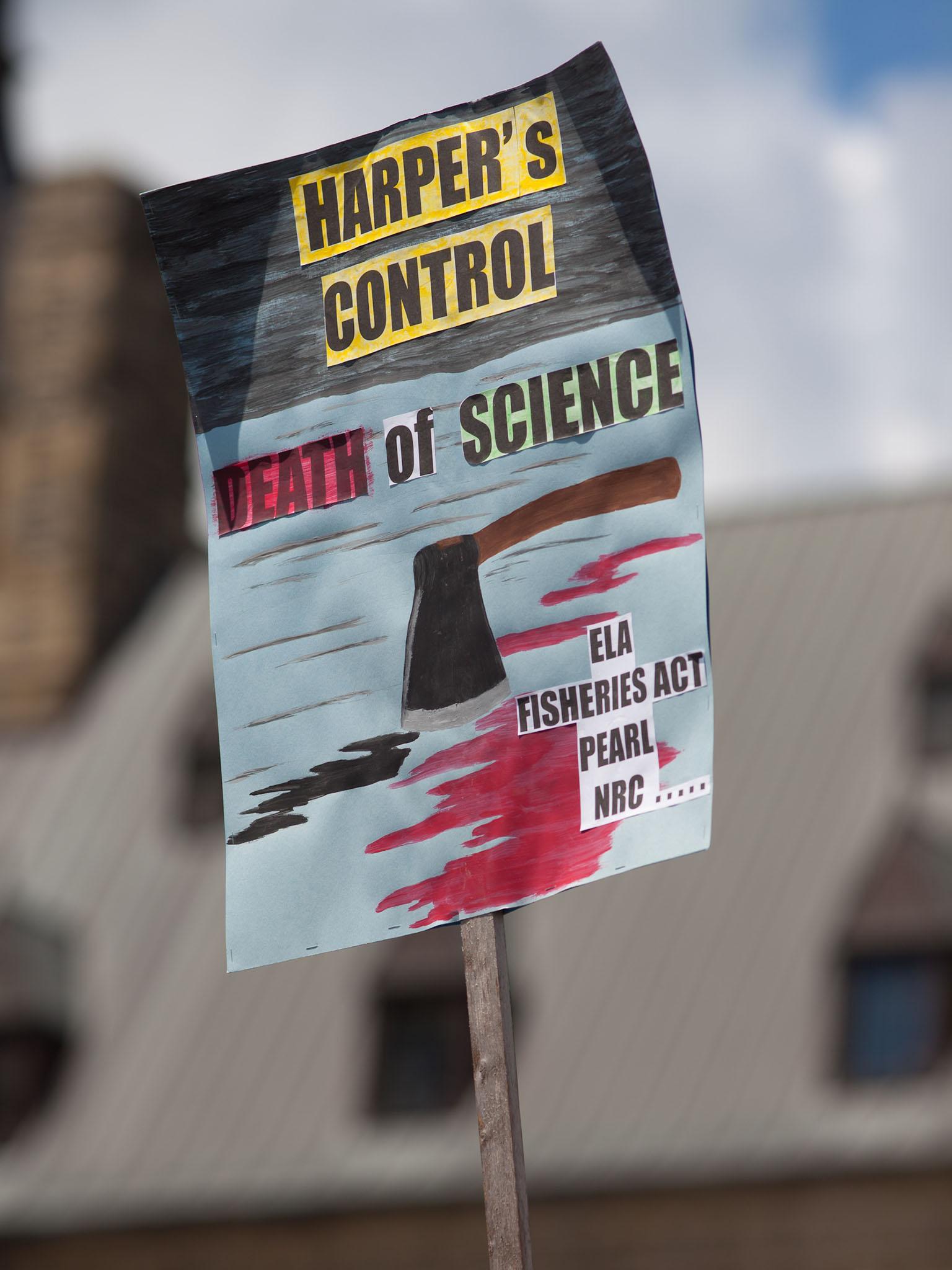

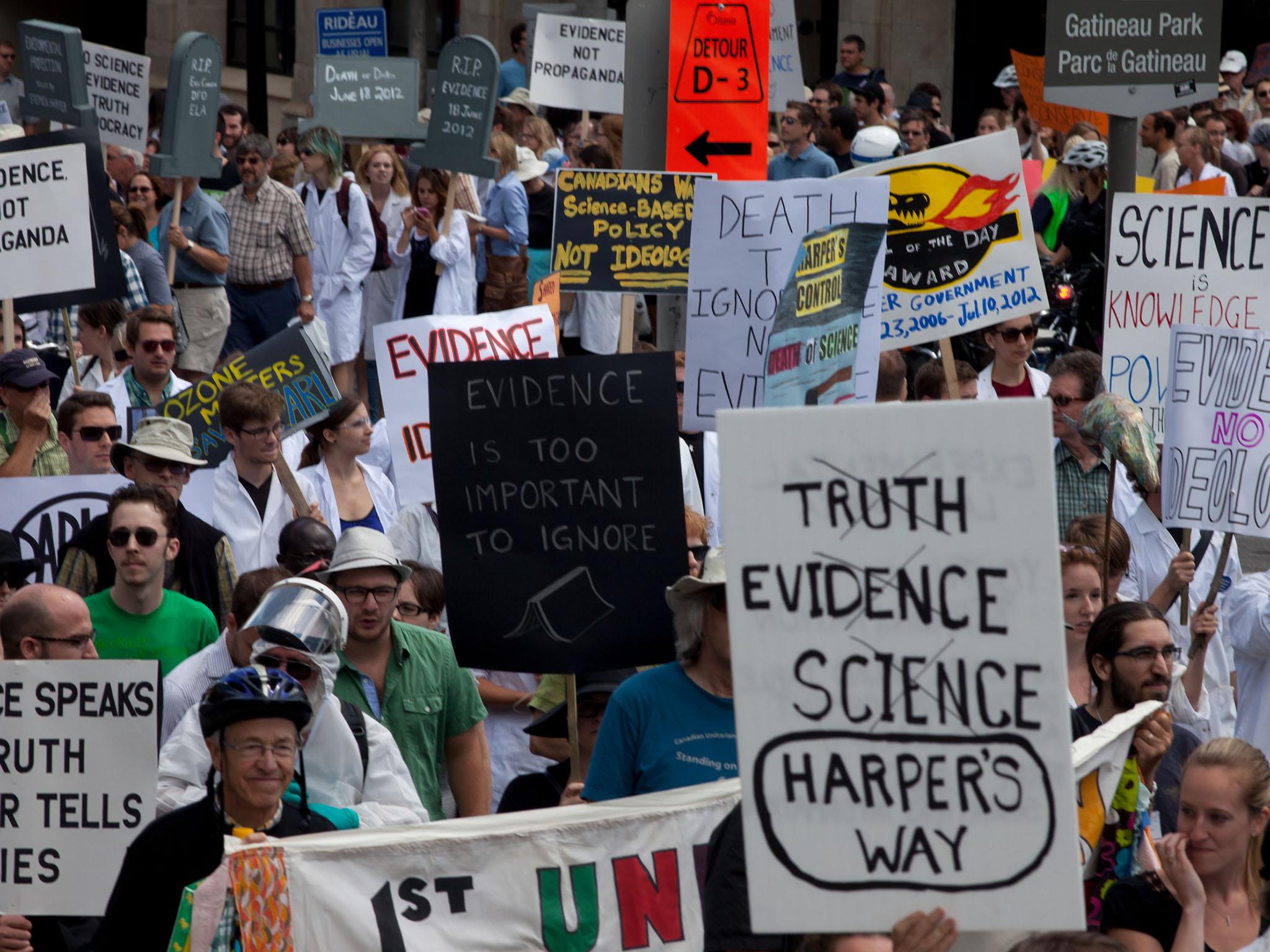

He was one of hundreds of researchers who gathered outside the Canadian parliament in a sea of white lab coats to hold a mock funeral mourning the “death of scientific evidence” in July 2012.

“Stephen Harper hates science” was the slogan of the day, a pointed dig at the then Prime Minister. And across Canada, it seemed to ring true in the wake of major cuts to federal science programmes, legislative changes diminishing the country’s budget for research, and the unsettling muzzling of federal scientists that was taking place.

“It was ridiculous, what we encountered. Things like Canadian scientists not being able to talk about research on, say, the extent of Arctic ice. Surely the Canadian people would want to know how much ice is left in the Arctic.” Findlay says. “Research was being done on the public’s dime and they had no access to it.”

“There were increasingly restrictive conditions under which scientists could communicate,” he adds. “It appeared to be a manifestation of Mr Harper’s enthusiasm, verging on obsession, with message control.”

In the end, Canadian science journalist Margaret Munro says the Harper government’s nearly decade-long clampdown on the scientific community contributed to its own undoing. “The muzzling of scientists was brought up repeatedly in the 2015 election campaign. It became a big issue,” she recalls. “And their war against information they didn’t like ended up toppling the government.”

‘Here we go again’

Now, however, it seems a similar trend is unfolding south of border under the Trump administration – a government that appears equally, if not more, determined to send a message of its own.

One of Donald Trump’s first decisions in power was to issue a chilling command that Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) officials and other government staff cease communications with the public. The agency, which oversees the government’s initiatives to fight climate change, is already expected to see budget cuts under the Trump administration, and a bill to “completely abolish” it altogether has also been drafted by a Republican US Representative.

The Trump government has also mandated that any studies or data from scientists at the EPA undergo review by political appointees before the can be released to the public. Meanwhile, important parts of the EPA’s website have already been quietly erased, with references to climate deals and other information on global warming disappearing from its pages.

Other federal agencies, including the Department of Health and Human Services and the Department of Agriculture have also been ordered to suspend communications with the public, although the latter department’s gag order was later lifted.

“My first thought was, ‘oh no... here we go again’,” says Steven Campana, who worked as a biologist at Fisheries and Oceans Canada under the Harper government until he retired in 2015.

Campana says that before Harper came into power, he was used to doing as many as 30 to 40 interviews about his research each year. Under Harper, “that number dropped to about maybe three”. Campana describes his frustration over one instance when he led a team that discovered “the very first method to determine the age of lobsters, crabs and shrimp”.

“This was something that had huge implications for the fishing industry. It was a totally good news story. There was no downside to it at all. But when I asked permission to speak to the media about it, I was not given that permission.” Campana says. Instead, colleagues in the United States had to share his research at a conference there, where it was “picked up by at least 100 media organisations around the world”.

“We got no credit for making this discovery. The Canadian government got no credit for it and the Canadian public got no credit for funding it,” Campana says. “Not being able to share my research with the general public was one of the most frustrating things I’ve ever experienced, not to mention demoralising.”

Katie Gibbs, the scientist and executive director of Evidence and Democracy who organised Canada’s “death of evidence” march nearly five years ago says American scientists should be prepared to face the same frustrations under the Trump administration, if not worse.

“The policies are definitely similar,” she says, “But Trump has been much more brazen in the way this has been implemented.”

“Harper understood these were going to be very unpopular policies, so he didn’t bring them in all at once,” Gibbs continues. “He did it in a sort of more stealthy manner. He did it one department at a time and it took a while for the science community and the public and the media to really see what was going on.”

That’s why, Gibbs says, the backlash to Harper’s policies took years to percolate, whereas the response to Trump’s swift clampdown on the science community has been almost immediate.

Just days after the Trump administration’s policies were put in place, American scientists had already reached out to Gibbs for help planning their own March for Science, which is now set to take place in Washington DC and around the world on 22 April. Tens of thousands of people have already indicated on social media that they plan to attend the protest, which has been branded as a march for “anyone who values empirical science”.

Gibbs says the “death of evidence” march in Canada was a turning point in creating public awareness about the toll the Harper government’s funding cuts and clampdown on the research community was taking on Canadian science. “It created a tipping point for this issue,” Gibbs says.

‘You never know what the next government might bring’

When Justin Trudeau defeated Stephen Harper in Canada's 2015 federal election, one of his first moves as Prime Minister was to issue a reversal of the restrictive policies banning federal scientists from communicating with the media and public.

Still, Gibbs says the effects of the Harper government’s clampdown can still be felt in the scientific community. “Even once some of these policies were overturned by our new government, you have to understand, we had a decade where government scientists could not speak about their work to the public and that really changes the culture of government science.

“It’s not like they go right back to communicating as much as they used to. It’s ingrained in the culture now that you don't speak out,” Gibbs says. “That’s why we’ve been pushing them to go a step forward in creating science integrity policies.

“Seeing what happened with Trump so quickly after a few years of pro-science policies with Obama shows us that we have to remain vigilant here and try to enshrine as many pro-science policies as we can, because you never know what the next government might bring.”

Until then

For scientists like Campana, the clampdown in the US is a painful reminder that members of the scientific community cannot grow complacent. “After what happened to us in Canada,” he says, “my advice to American researchers is to make your concerns known as widely and as loudly as you can early on, rather than just hunkering down and hiding.”

“That can be difficult to do. They may even end up getting fired,” he adds. “But it may well be that American scientists have to adopt certain guerrilla measures to escape this gag order.”

Gibbs says there are several steps federal scientists can take to protect their research and to ensure that future work reaches the public:

Save your data

“Tangibly, a first step is to save any information you can and make sure you have it backed up,” Gibbs says. “That means putting your data sets on USB keys or external hard drives and taking it home. Make sure that you have access to all the data you need to do your research.”

Partner with researchers outside federal government

“It’s hugely important for government scientists to find colleagues that they can work with either outside of government in the US, or even international colleagues who can help them get research out if they are finding that it is censored through channels inside government,” Gibbs says.

Campana adds that he and other federal researchers would speak with media contacts and politicians about their work off the record. They would also ask non-federal scientists to share their research on their behalf. “There were various ways to circumvent the system,” Campana says.

A Scientists Network has also been set up online to provide support to federal researchers in the US. Through the network, Gibbs says researchers will be able to share their work anonymously or find new job opportunities. She adds that scientists in US “are going to have to think long and hard about what kind of role they want to play in all of this and if they are going to follow these orders, versus being to willing to, for example, leak that information even if it means risking their jobs and that’s the kind of decision that only they can come to”.

Document everything

One of the difficulties Gibbs says the Canadian scientific community faced in both gauging and demonstrating how widespread the clampdown on federal scientists really was, was that most evidence of it was anecdotal.

“Nothing was written down when this was occurring, so we didn't have any paper trail of it,” Gibbs says. She says federal researchers would rarely receive orders in writing or by email. Rather, they would be delivered over the phone or in person. “They were smart enough not to leave that paper trail,” Gibbs adds.

“Scientists should document absolutely every incidence they see of being told they can't do an interview, changes to communication policies, any time they can't publish their research, any time there is political interference in their research. Keeping a really detailed account of when that is happening is going to be helpful in terms of being able to demonstrate what is really going on.”

Engage the public

“Unless scientists can convince the public in a compelling fashion that this is important to their individual wellbeing, they are not going to make much headway,” Findlay says.

“Mr Trump is a populist and he got to where he is by manipulating the message to appeal to the populace. Scientists have to get their own message out and become a bit populist about it. Not by manipulating the message, but by making sure it is clear to the public what the impacts of these kinds of restrictions are so the public can make their own decisions.”

Remember your rights

“Americans have the First Amendment in their Constitution,” Findlay says. “We don't have any such thing in Canada. We do have our Charter of Rights and Freedoms, where freedom of speech is defended. But the American people have always held up the First Amendment as the shining light of their Constitution. When you start restricting the ability of scientists to talk to the public about their science, that's a substantial infringement on that constitutional right.”

“When we were out talking to everyday Canadians, they understood the value of science. They understood their ability to make informed decisions is based on open and transparent information,” Findlay says. “Scientists are a good source of credible information. And that message resonated with a lot of Canadians and I suspect it will resonate with a lot of people in the US as well.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments