Traces found of the earliest Britons from 900,000 years ago

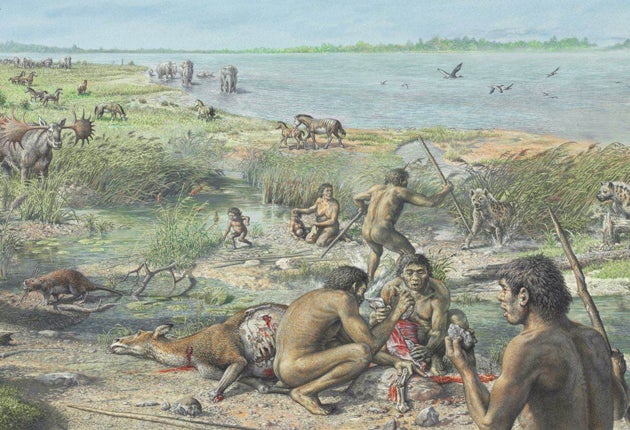

Mammoths trampled the undergrowth, giant elk stalked the land, and hyenas and sabre-toothed cats took no hostages. This was normal for Norfolk 800,000 years ago, according to scientists who have found the earliest evidence of human settlement in Britain.

Excavations on a Norfolk beach near the village of Happisburgh have unearthed more than 70 flint tools that had been honed by the first-known prehistoric people to live in Britain. The stone tools have been dated to between 1 million and 800,000 years old. Scientists said the flint tools were probably used by these early Britons for cutting meat or piercing animal skins. Until the discovery of the tools, there was little evidence to suggest that prehistoric humans of this period lived further north than the Alps and the Pyrenees.

No human fossils have yet been uncovered from the site so scientists do not yet know which species of prehistoric human lived there, but they believe the most likely candidate was homo antecessor, or "Pioneer Man", who was living at about the same time in caves on the Iberian peninsula.

Other fossilised remains from the Norfolk excavations showed that the area was on the edge of a cool, northern "boreal" forest within walking distance of a nearby estuary where the ancient River Thames emptied into the North Sea, many miles further north than the position of the present Thames Estuary. The land mass, which was still connected to mainland Europe, would have teemed with an array of plants and animals, from tiny voles to giant elk with ten-foot antlers.

"The flood plain would have been dominated by grass, supporting a diverse range of herbivores, such as mammoth, rhino and horses," said Simon Parfitt of University College London, who was the lead author of the study published in the journal Nature. "Predators would have included hyenas, sabre-toothed cats and, of course, humans."

Fossil beetles and pollen suggest the summers were slightly warmer than today but the winters were considerably colder, similar to those of southern Scandinavia now. This implies that these early Britons were likely to have used fire, clothed themselves in animal skins, and used food stores to see them through winter.

Professor Chris Stringer of the Natural History Museum in London, and director of the Ancient Human Occupation of Britain project, said that the discovery of man-made stone tools in the Happisburgh excavations suggested a much earlier occupation of Britain than previously supposed.

"These finds are by far the earliest known evidence of humans in Britain, dating at least 100,000 years earlier than previous discoveries," he said. "They have significant implications for our understanding of early human behaviour, adaptations and survival, as well as when and how our early forebears colonised Europe after their first departure from Africa." Whoever made the stone tools, they were not the direct ancestors of present-day Britons. Professor Stringer said that there were at least nine separate colonisations of Britain over the past 1 million years with the eight previous colonisations dying out with each subsequent ice age.

Nick Ashton of the British Museum said that the discovery shows that early humans were capable of coping with the cold winters and short winter daylight of a northern climate. "This demonstrates early humans surviving in a climate cooler than that of the present day," Dr Ashton said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks