The smell of fear can be inherited, scientists prove

Study shows scents associated with terror may be passed on for two male generations

Scientists have shown for the first time that fear can be transmitted from a father to his offspring through his sperm alone in a ground-breaking study into a new kind of genetic inheritance.

Experiments on mice have demonstrated that they can be trained to associate a particular kind of smell to a fearful memory and that this fear can be passed down through subsequent generations via chemical changes to a father’s sperm cells.

The findings raise questions over whether a similar kind of inheritance occurs in humans, for example whether men exposed to the psychological trauma of a foreign war zone can pass on this fearful behavioural experience in their sperm to their children and grandchildren conceived at home.

The researchers emphasised that their carefully controlled study was carried out on laboratory mice and there are still many unanswered questions, but they do not discount the possibility that something similar may also be possible in people.

“I think there is increasing evidence from a number of studies that what we inherit from out parents is very complex and that the gametes – the sperm and eggs – may be a possible mechanism of conserving as much information as possible from a previous generation,” said Kerry Ressler, professor of psychiatry at Emory School of Medicine in Atlanta, Georgia.

“The biggest interpretation of this research, if it holds up across mammals, is that it may be possible for certain traits such as the fearful experience of a parent to be transmitted to subsequent generations,” Professor Ressler said.

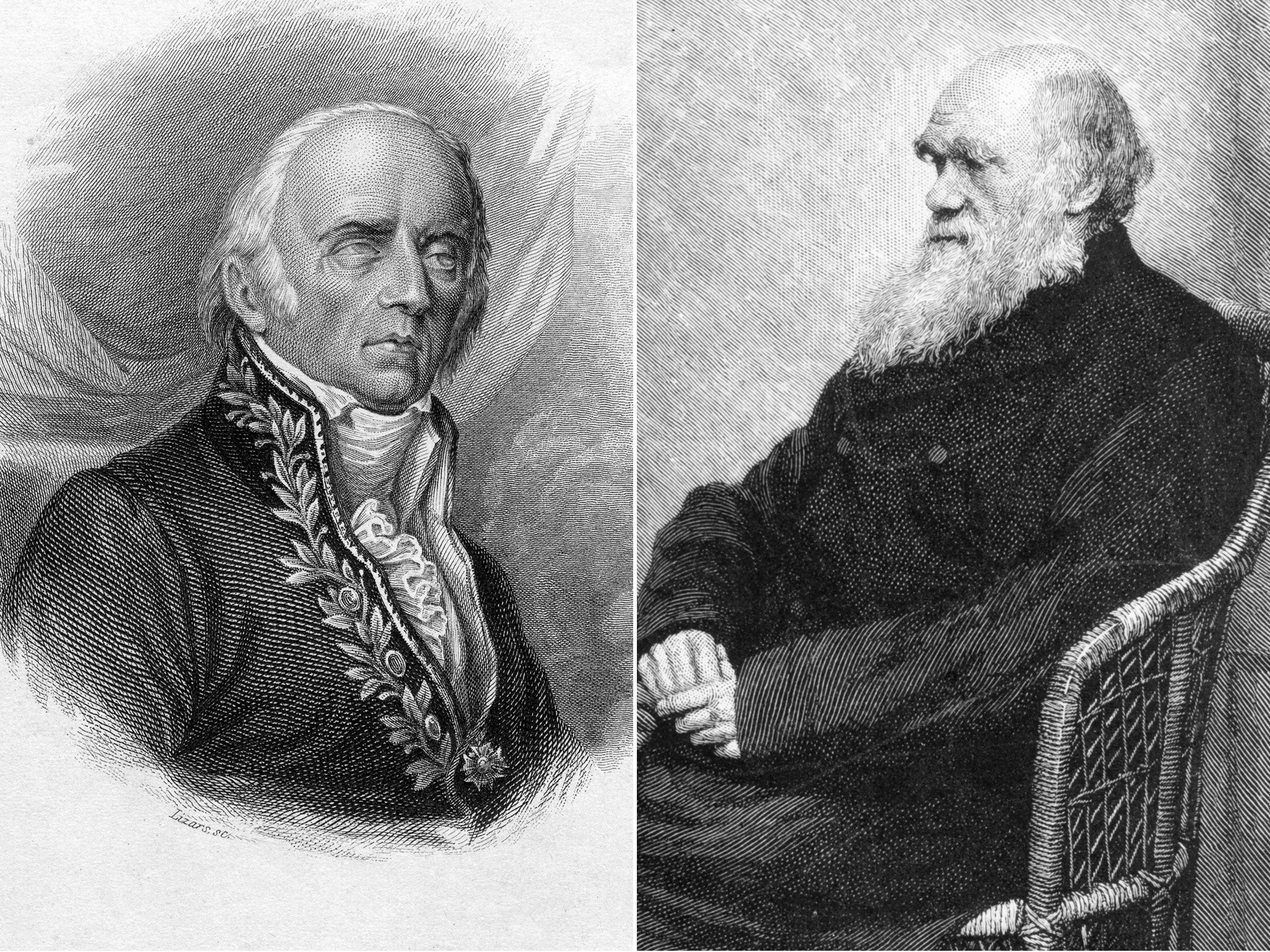

The findings also lend some support to a discredited theory known as the "inheritance of acquired characteristics", promulgated by Jean-Baptiste Lamarck in the late 18th Century. Lamarck postulated that organisms can pass on physical features they developed during their lifetime to their offspring, such as the long neck of giraffes which stretched to reach the highest leaves on a tree.

Butt this idea was later supplanted by Charles Darwin's theory of natural selection, which was further supported by the discovery of genes and Mendelian inheritance. The latest study, however, shows that a kind of Lamarckism may in fact exist in nature as a result of environmental influences directly affecting epigenetic changes to an organism's DNA.

The study, published in the journal Nature Neuroscience, trained male mice to associate the smell of the chemical acetophenone, which smells like cherry blossom, with a mild electric shock. These mice soon displayed fear whenever they were exposed to acetophenone on its own.

Breeding experiments showed that this fear of acetophenone could be transmitted to two further generations, the sons and grandsons of the original male mice. This inheritance must have passed on in sperm as the original males were not allowed to come into contact with their offspring.

Further experiments involving the fertilisation of mouse eggs using IVF techniques confirmed that the fear trait, which was resulted in specific changes to the brains of the mice involve the sense of smell, was transmitted in the sperm as “epigenetic” changes to the proteins surrounding the DNA of the sperm cells.

“While the sequence of the gene encoding the receptor that responds to the odour is unchanged, the way that gene is regulated may be affected,” Professor Ressler said.

“There is some evidence that some of the generalized effects of diet and hormone changes, as well as trauma, can be transmitted epigenetically,” he said.

“The difference here is that the odour-sensitivity-learning process is affecting the nervous system – and, apparently, reproductive cells too – in such a specific way,” he added

Similar studies on female mice, where their pups were immediately fostered by other females, showed that the same kind of mechanism may also occur through egg cells. However, it is more difficult in this instance to eliminate the possibility that the changes occurred in the foetus rather than in the DNA of the females’ eggs.

The study concluded that “ancestral experience before conception” may be an under-appreciated influence on the behaviour of adults, particularly when psychological conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder, phobias and anxieties are involved.

“Knowing how the experiences of parents influence their descendants helps us to understand psychiatric disorders that may have a trans-generational basis, and possibly to design therapeutic strategies,” Professor Ressler said.

Professor Marcus Pembrey, a paediatric geneticist at University College London, said that the study is important because it provides compelling evidence for the biological transmission of the “memory” of a fearful ancestral experience.

“It is high time public health researchers took human trans-generational responses seriously. I suspect we will not understand the rise in neuropsychiatric disorders or obesity, diabetes and metabolic disruptions generally without taking a multi-generational approach,” Professor Pembrey said.

Professor Wolf Reik, head of epigenetics at the Babraham Institute in Cambridge, said: “These types of results are encouraging as they suggest that trans-generational inheritance exists and is mediated by epigenetics, but more careful mechanistic study of animal models is needed before extrapolating such findings to humans.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks