The fossils that could reveal how man walked out of Africa

Children's footprints from 2,000 years ago offer clues to development of human gait

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

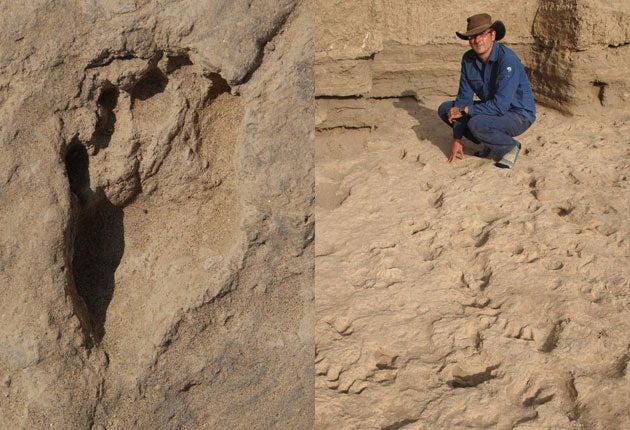

Your support makes all the difference.The fossilised footprints of a group of young children playing as they scampered after livestock have been discovered by a team of British palaeontologists in Namibia.

The impressions revealed that as the children followed the herd, they were bubbling over with energy, skipping and jumping across the muddy terrain. For fossilised remains, the prints are relatively youthful, being just under 2,000 years old.

All of the children's footprints, along with scores more human tracks in the Khuiseb Delta, are being recorded in detail with an optical laser scanner and are to be placed in a digital archive.

The collection, the first of its kind, is designed to hold every single fossilised footprint left by humans and their ancestors, with the aim of trying to shed light on how humans evolved.

All known fossilised human footprints, whether from ancestral species or Homo sapiens, are being revisited by researchers and recorded digitally. Among them are the oldest-known footprints, in Tanzania, of a relative of "Lucy" – the female member of the only known hominin to be living in the area at the time: a small-brained biped called Australopithecus afarensis.

Also undergoing fresh analysis are tracks from Kenya that caused a sensation last year, and prints in Australia which, some researchers claim, show that prehistoric Aborigines could run faster than Jamaican sprinter Usain Bolt – although this is hotly disputed.

Professor Matthew Bennett, of Bournemouth University, part of a team that discovered the second-oldest footprints left by a hominid, said the digital resource would help researchers work out how ancient people walked, and in doing so discover why it was that mankind's ancestors left Africa.

The team's development of an optical laser scanner helped them conclude that Homo erectus walked just like Homo sapiens does, meaning that modern capabilities had already developed at least 1.5 million years ago. They touched the ground with their heels before transferring the weight to the balls of their feet, then rolling towards the big toe before lifting up again.

So successful was this work that the National Environment Research Council (NERC) agreed to provide funding to establish the digital archive of all human footprints. The project is being carried out by Bournemouth University with the Primate Evolution and Morphology Group at the University of Liverpool.

The shape and mechanics of the foot, said Professor Bennett, offer great insight into the rest of the human anatomy, the gait and the behaviour that was possible in exploiting the environment. Being able to walk on two legs was one achievement; being able to walk for hours across a hot and dry landscape in search of food was quite another.

Few fossilised human foot bones have been found. Being at the extremities of the body, feet are often the first parts of a body that scavengers will chew on, and being made up of lots of small bones and soft tissue they are easily destroyed.

The use of the digital images means researchers can see prints in 3D, with accuracy to one-100th of a millimetre. "Footprints are even better than fossil bones," said Professor Bennett.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments