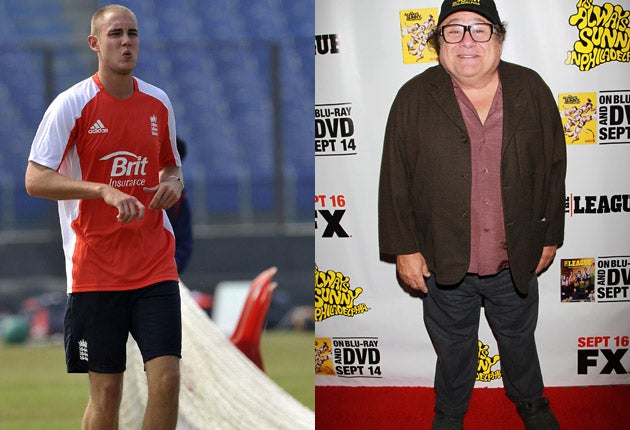

The descent of man?

Our species is still evolving, but future humans might be more like Danny DeVito than Stuart Broad. Olly Bootle explains why

Ever since Charles Darwin formulated his theory of evolution by natural selection 150 years ago, scientists have wondered whether the process still applies to humans. Evolution may have made us, but at some point, did we stop evolving?

There's no question that we're unique in the animal world. While a bear which found itself stranded in the arctic would, over millennia, evolve thick blubber to keep itself warm, humans could make clothes and light fires. Or we could just build a boat and leave.

And so scientists suspected that by adapting to environmental change – the driver of natural selection – using our ingenuity, we might have stopped ourselves evolving. The late Stephen Jay Gould, one of the most respected of evolutionary biologists, once said: "There has been no biological change in humans in 40,000 or 50,000 years. Everything we call culture and civilisation we've built with the same body and brain."

It turns out that he, and many others, were wrong.

Our ability to map the human genome has revolutionised our understanding of human evolution. By comparing the DNA of thousands of people from around the world, scientists are able to see how different we all are genetically. And that means they can see if different people have evolved apart from each other – whether our species has continued to evolve.

As Dr Pardis Sabeti, a geneticist at Harvard University, puts it: "We are living records of our past, and so we can look at the DNA of individuals from today and get a sense of how they all came to be this way. It's very exciting. We are starting to piece together bits of information to get this sort of coherent picture of human evolution."

In a recent study, Dr Sabeti and her team found 250 areas of the genome that have continued to change via natural selection in the last 10,000 years or so. Some of them, like skin colour, are obvious. But our metabolism has also changed to allow us to digest some things that we couldn't in the past; there may have been changes to our thermoregulatory capacities; high-altitude populations have evolved to allow them to cope with a lack of oxygen; and, perhaps unsurprisingly, disease has been one of the greatest drivers of our recent evolution – anyone who's lucky enough to have some sort of genetic immunity to a disease is at an immediate advantage, and their genes will prosper in future generations.

So clearly our technology and inventiveness didn't stop us evolving in the past. But the world today is very different to the world a few thousand years ago, or even last century. Nowadays, in the developed world, almost everyone has a roof over their heads and enough food to survive. It is very rare for cancer to kill anyone before they've lived long enough to have children and pass on their genes. So what is there for natural selection to act on?

As Professor Steve Jones, a geneticist at University College London, explains: "In Shakespeare's time, only about one English baby in three made it to be 21. All those deaths were raw material for national selection, many of those kids died because of the genes they carried. But now, about 99 per cent of all the babies born make it to that age." This leaves Professor Jones in little doubt about the reality today: "Natural selection, if it hasn't stopped, has at least slowed down."

But it's important to remember, natural selection is only driven by death inasmuch as death stops people from breeding, and passing on their genes. And although in the developed world today, almost everyone lives long enough to pass on their genes, many of us choose not to. Surely that will drive natural selection in the same way as if some people died before being able to pass on their genes?

The realisation that differing fertility levels might be driving change in our species has led evolutionary biologist Stephen Stearns, from Yale University, to look at evolution in a radical way. By analysing data gathered in an otherwise unremarkable town, Framingham in Massachusetts, he can tell how the people of the town will evolve in the coming generations. His calculations have convinced him that people are still evolving, and in a surprising direction. "What we have found with height and weight basically is that natural selection appears to be operating to reduce the height and to slightly increase their weight."

Stearns points out that this isn't just a case of people eating more: "There's no doubt that there are big cultural effects on things like weight. But we can estimate what the genetic component is of the variation in height or the variation in weight."

But Stearns believes it's unlikely that we'll head in the same direction forever. "I think what's very probably going on is that selection is moving a population up and down all the time, it goes off in a certain direction for a while and then it goes back in the other direction. It's only if you get a significant change in the environment that it will then continuously go in a new direction."

So it appears that we'll never stop evolving. As for where it will take us in the long term, it's impossible to say. All we can do is look at the likely changes to the world we live in, and speculate as to how they might affect us.

When it comes to changes in our future, it's hard to think of any that will have as much of an impact on our evolution as our ability to tamper directly with our genes.

Dr Jeff Steinberg runs The Fertility Institutes in Los Angeles, a fertility clinic that helps couples to conceive using IVF. Using a technique called Pre-implantation Genetic Diagnosis (PGD), embryos are screened to try to ensure they're free of genetic diseases.

During the screening process, it's obvious whether an embryo is male or female, and couples can choose the sex of the embryo to be implanted in the womb. This is illegal in the UK, but in the US, "anyone can choose. They can choose a boy, or a girl, and we've done this close to 9,000 times now," Dr Steinberg says.

But genetic diseases and the sex of the embryo aren't the only traits that Dr Steinberg's technicians can see. The clinic attracted controversy recently when it announced that it would allow parents to choose the eye and hair colour of their offspring. "We heard from a lot of people, including the Catholic Church, that had some big problems with it," says Dr Steinberg. "So we retracted it, even though we can do it, we're not doing it."

Dr Steinberg is in little doubt that PGD, and genetic engineering more broadly, will play a major role in humanity's future. "I think it will play a huge part in our evolution and I think rightfully so. We need to be cautious about it because it can go right and it can go wrong, but I think trying to remove it as part of our future evolution is just a task that's not going to be accomplished."

It turns out that our culture and technology, like genetic engineering, can change our world so much that rather than sheltering us from natural selection, it can actually drive our evolution.

As Stearns says: "We see rapid evolution when there's rapid environmental change, and the biggest part of our environment is culture, and culture is exploding. We are continuing to evolve, our biology is going to change with culture and it's just a matter of not being able to see it because we're stuck in the middle of the process right now."

It seems that the direction of our future evolution may be driven not by nature, but by us.

Olly Bootle's Horizon film Are We Still Evolving? is on BBC2 tomorrow at 9pm.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments