The brainboxes born 1.2m years ago

Discovery of fossilised pelvis forces scientists to revise view of Homo erectus

The discovery of a fossilised pelvis of a woman who lived 1.2 million years ago has resolved a long-standing debate over when in the history of human evolution it was possible for babies with large brains to be born.

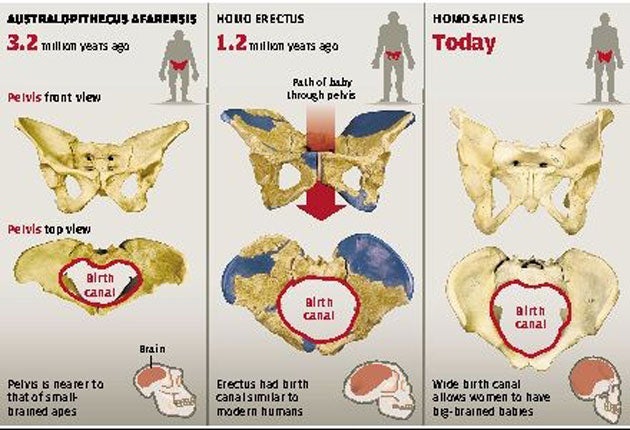

Humans are unique for the relatively large heads of their newborn babies but, until now, it was not known when women developed the wide pelvis needed to give birth to big-brained babies. Now scientists believe they can finally answer the question after discovering the most intact female pelvis of Homo erectus, a species that predated our own species, H. sapiens.

The large human brain, relative to body size, has enabled man to dominate his environment with the use of language and tools. The wide pelvis of H. erectus shows that large brains could grow in the womb of early humans long before H. sapiens first emerged on the scene about 195,000 years ago.

Scientists led by Sileshi Semaw of Indiana University in Bloomington found the fossilised fragments of the near-complete pelvis at Gona in the Afar region of Ethiopia, where some of the most important early human fossils have been unearthed. A reconstruction of the fragments showed that the H. erectus female had a birth canal that was 30 per cent larger than earlier estimates based on the fossilised pelvis of a juvenile male dated to about 1.5 million years ago. This would have allowed aH. erectus female to give birth to babies with brain sizes of up to 315 millilitres (10.6 fluid oz), which is between 30 and 50 per cent of the adult brain size for this species. "This is the most complete female Homo erectus pelvis ever found from this time period," Dr Semaw said.

"This discovery gives us more accurate information about the Homo erectus female pelvic inlet and therefore the size of their newborns." The study, published in the journal Science, compares the newly discovered pelvis with that of Lucy, an earlier hominid belonging to the species Australapithcus afarensis which lived about 3.2 million years ago, also in what is now the Afar region of Ethiopia. The comparison shows that Lucy's birth canal did not permit the birth of large-brained newborns, so the evolution of this trait almost certainly occurred around the time of H. erectus, a species that had migrated out of Africa and into Asia.

"The female Homo erectus pelvic anatomy is basically unknown. And as far as the fossil pelvis of ancestral hominids goes, all we've had is Lucy, and she is very much further back in time from modern humans," Dr Semaw said.

It was thought until now that the brain of H. erectus grew rapidly after birth, in much the same way that the brains of babies today grow in the first few months of life. But the discovery of the wide pelvis suggests that H. erectus had got a head start by growing within the womb – again like modern babies.

The scientists say the wide pelvis tells them much about these human ancestors. They suggest, for instance, that the babies of H. erectus would have grown up faster than modern humans, without the extended childhood that marks out man as being different from chimpanzees and other apes.

There would also have been a limit on how wide the human pelvis could grow because the bone is central to the bipedal gait of humans.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks