The battered look: How prehistoric punch-ups shaped how humans look today

New study suggests facial features evolved to protect our ancestors from injury

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Bare-knuckle fighting helped to shape the human face which evolution has designed to minimise the damage inflicted by a fast-moving fist, according to a radical new theory about how violence changed the way we looked compared to our ape-like ancestors.

The transition in facial structure from apes to early hominins had previously been explained largely by the need to chew on nuts and other hard foods that needed crushing which led to a robust jaw, large molar teeth, a prominent brow and strong cheek muscles.

However, scientists have devised another plausible explanation based on the need for the face to be buttressed against the impact of flying fists which had become a principal weapon in unarmed combat between competing males.

“We suggest that many of the facial features that characterise early hominins evolved to protect the face from injury during fighting with fists,” said David Carrier and Michael Morgan in a study published in the journal Biological Reviews.

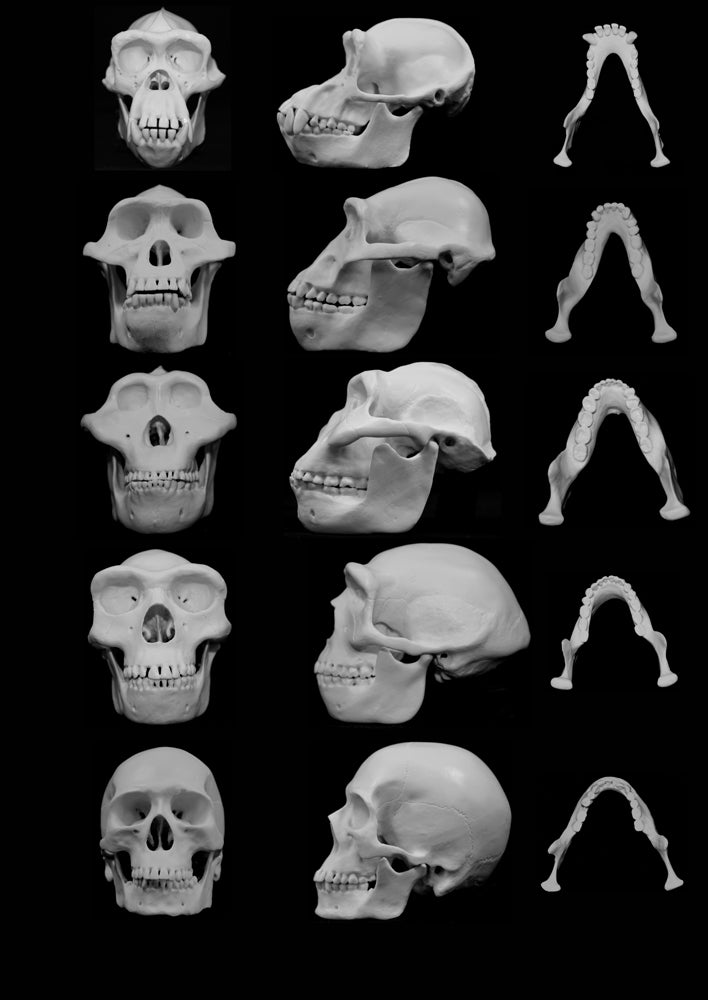

The researchers analysed the facial bone structures of a number of hominins, such as an early human ancestor known as Australopithecus, and compared them to apes and modern man. They found that the parts of the face that changed most were the ones most likely to be damaged in a fist fight.

They also found that these changes in facial anatomy closely coincided with the ability of the early hominins to clench their fists and to use them as swinging clubs in a fight – a key tactical change from the biting and scratching preferred by fighting apes.

“Compared to apes like chimps and gorillas, early hominins had very robust jaws, with large molar teeth and strong jaw muscles. They also have very stout cheek bones and brow ridges,” said David Carrier of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

“The australopiths were characterised by a suite of traits that may have improved fighting ability, including hand proportions that allow formation of a fist, effectively turning the delicate musculoskeletal system of the hand into a club for striking,” Dr Carrier said.

“If indeed the evolution of our hand proportions were associated with selection for fighting behaviour you might expect the primary target, the face, to have undergone evolution to better protect it from injury when punched,” he said.

With his colleague Mike Morgan, a medical doctor at Utah University, Dr Carrier analysed the facial bones that were most likely to be fractured in fights between modern humans and found that these were the same bones that were most likely to have been changed during human evolution.

“When modern humans fight the face is the primary target. The bones of the face that suffer the highest rates of fracture from fights are the bones that show the greatest increase in robusticity during the evolution of early bipedal apes, the australopiths,” Dr Carrier said.

“These are also the bones that show the greatest difference between women and men in both australopiths and modern humans,” he said.

The gender differences in facial bones supports the view that they evolved to buttress the face against flying fists given that fights between males are more common than those between females.

“In other words, male and female faces are different because the parts of the skull that break in fights are bigger in males,” he said.

“In both apes and humans, males are much more violent than females and most male violence is directed at other males. Because males are the primary target of violence, one would expect more protective buttressing in males and that is what we find,” he added.

The large, thickly enamelled molar teeth of australopiths may have allowed the energy of an upward blow to the jaw, for instance, to be transferred from the lower jaw to the skull, allowing the energy to be absorbed with the help of jaw muscles, the scientists suggested.

“What our research has been showing is that many of the anatomical characters of great apes and our ancestors, the early hominins – such as bipedal posture, the proportions of our hands and the shape of our faces – do in fact improve fighting performance,” Dr Carrier said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments