Armies of ‘crazy’ acid-spewing red ants taking over Texas homes may soon be wiped out by killer fungus

In some places, scientists say nearly two-thirds of the ant population has disappeared entirely

With homes in many parts of Texas overrun by armies of red ants swarming electrical devices, breaker boxes and AC units, causing shorts and other damage, scientists said a naturally-occurring fungus could “crush” local populations of these “crazy” insects.

When these invasive, acid-spewing tawny ants – originally from South America – move into a new area, they cause major headaches for homeowners, said scientists from the University of Texas in the US.

Over the past 20 years, researchers said these ants have wreaked havoc as they have spread across the southeastern US, driving out native insects as well as small animals, with even reports of the acid-spewing ants blinding baby bunnies.

Now, a new study, published on Monday in the journal PNAS, has found that infection by a fungal pathogen Myrmecomorba nylanderiae causes the population of these ants to collapse to local extinction, providing a way to develop effective biological control of the invading species.

“I think it has a lot of potential for the protection of sensitive habitats with endangered species or areas of high conservation value,” Edward LeBrun, lead author of the study, said in a statement.

While it is currently “impossible” to predict how long it may take for the fungus to infect and kill off any of the ant populations, he said the finding is “a big relief” since “it means these populations appear to have a lifespan”.

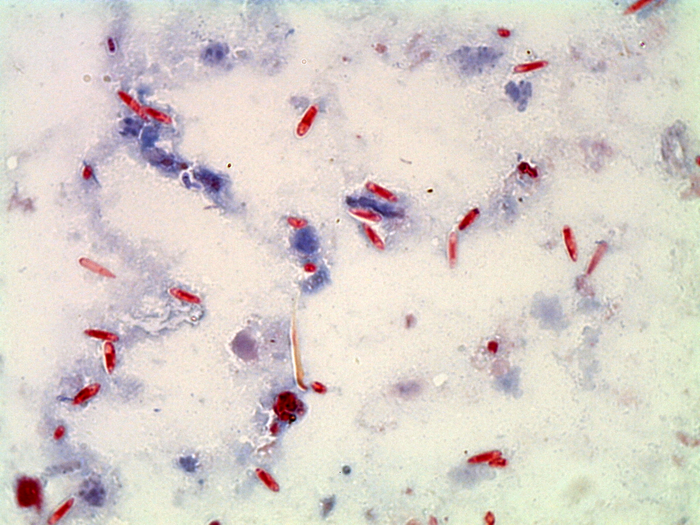

The fungus species was initially discovered when scientists including Dr LeBrun were studying ants collected in Florida and noticed some had abdomens swollen with fat.

On closer analysis, they found spores from a microsporidian, a group of fungal pathogens known to hijack insect fat cells and turn them into spore factories.

Researchers are yet to find where the fungus may have come from but speculate it may have originated from the ant’s native range in South America or from another insect.

In the new study, assessing 15 local populations of the ants for eight years, scientists found that every population that harboured the pathogen declined.

They say nearly two-thirds (62 per cent) of the ant populations disappeared entirely.

Researchers speculate these colonies likely collapsed since the fungus shortens the lifespan of worker ants, making it harder for a population to survive through winter.

“We report long-term studies demonstrating that infection by a microsporidian pathogen causes populations of a globally significant invasive ant to collapse to local extinction, providing a mechanistic understanding of a pervasive phenomenon in biological invasions,” scientists wrote in the study.

However, researchers said the fungus may not lead to the extinction of a population since the infected population normally goes through “boom-and-bust cycles” as the frequency of infection waxes and wanes.

They added that the pathogen seems to leave native ants and other insects unharmed, making it a likely “ideal” biocontrol agent.

Scientists also tested the effectiveness of the fungus by deploying it at the Estero Llano Grande State Park in Weslaco, Texas, in 2016, which was losing its insects, scorpions, snakes, lizards and birds to these ants.

In the park, they said baby rabbits were being blinded in their nests by swarms of these acid-spewing ants.

“They had a crazy ant infestation, and it was apocalyptic, rivers of ants going up and down every tree. I wasn’t really ready to start this as an experimental process, but it’s like, OK, let’s just give it a go,” Dr LeBrun said.

Scientists put the ants they had collected from other sites that were already infected with the fungal pathogen into nest boxes near crazy ant nesting sites in the state park.

They then placed hot dogs around the exit chambers to attract the local ants and merge the two populations.

In just one year of the study, researchers said the fungal disease spread to the entire ant population in Estero and within two years, the ant numbers plunged.

Now, the acid-spewing invasive ants are nonexistent, and native species are returning to the area, scientists said.

They plan to test the new biocontrol approach at other sensitive Texas habitats infested with these ants.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks