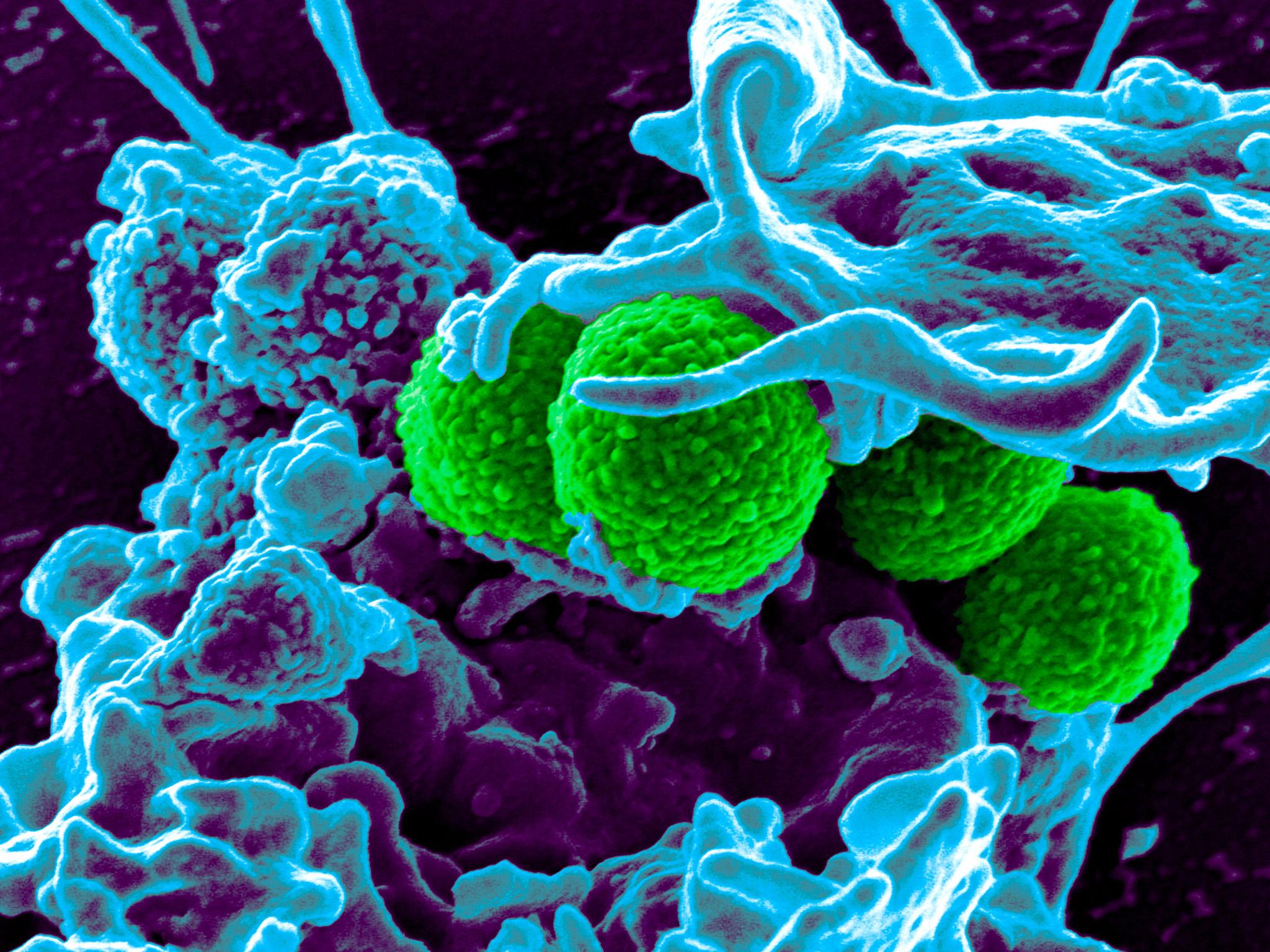

Antibiotic resistance: Superbugs can be killed by modifying existing drugs, scientists discover

One type of antibiotic is found to kill bacteria by ripping it open by brute force, a previously unknown method that could help make a whole new generation of drugs

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In the evolutionary arms-race between deadly bacteria and the antibiotics used by doctors to kill them, the bugs have very definitely been gaining the upper hand in recent years.

But, amid growing reports of bacteria resistant to even the ‘last resort’ antibiotics, comes the news that scientists have found a new way that some existing drugs can still be effective.

Normally antibiotics must bind to a bacteria cell in order to kill it, like putting a key in a locked door.

But the researchers found that one drug exerted such a strong physical force on the bacteria that it “tore the door off its hinges”.

The hunt is now on for other antibiotics with similar properties to create a “new generation” of drugs capable of defeating even the most resistant superbugs.

Last year, growing concern about antibiotic resistance prompted then Prime Minister David Cameron to warn of "catastrophic consequences" if the problem was not dealt with across the world. The UK was instrumental in organising a meeting at the United Nations to discuss the issue.

One of the researchers, Dr Joseph Ndieyira, of University College London, said: “Antibiotics work in different ways, but they all need to bind to bacterial cells in order to kill them.

“Antibiotics have ‘keys’ that fit ‘locks’ on bacterial cell surfaces, allowing them to latch on.

“When a bacterium becomes resistant to a drug, it effectively changes the locks so the key won’t fit any more.

“Incredibly, we found that certain antibiotics can still ‘force’ the lock, allowing them to bind to and kill resistant bacteria because they are able to push hard enough.

“In fact, some of them were so strong they tore the door off its hinges, killing the bacteria instantly.”

The study tested a powerful antibiotic called vancomycin, used as a last-resort treatment for infections like MRSA, and another called oritavancin, used to treat skin infections.

“We found that oritavancin pressed into resistant bacteria with a force 11,000 times stronger than vancomycin,” says Dr Ndieyira.

“Even though it has the same ‘key’ as vancomycin, oritavancin was still highly effective at killing resistant bacteria.

“Until now it wasn’t clear how oritavancin killed bacteria, but our study suggests that the forces it generates can actually tear holes in the bacteria and rip them apart.”

This way of killing bacteria has not been seen before.

“Oritavancin molecules are good at sticking together to form clusters, which fundamentally changes how they kill bacteria,” Dr Ndieyira said.

“When two clusters dig into a bacterial surface they push apart from each other, tearing the surface and killing the bacteria.

“Remarkably, we found that conditions at the bacterial surface actually encourage clustering which makes antibiotics even more effective.”

The researchers have now developed a mathematical model that could be used to screen for new antibiotics that have the same “brute force” approach.

“Our findings will help us not only to design new antibiotics but also to modify existing ones to overcome resistance,” Dr Ndieyira said.

“Oritavancin is just a modified version of vancomycin, and now we know how these modifications work we can do similar things with other antibiotics.

“This will help us to create a new generation of antibiotics to tackle multi-drug resistant bacterial infections, now recognized as one of the greatest global threats in modern healthcare.”

The growth of antibiotic resistance has been driven partly by over-prescription of the drugs for conditions like the common cold, which is a virus, not a bacterium, and is therefore unaffected.

Antibiotics have also been used in agriculture to boost the growth of livestock.

The researchers' findings were published in the journal Scientific Reports.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments