Strain of HIV virus found in monkeys is cleared by vaccine

Vaccine could be used on humans in clinical trials within two years

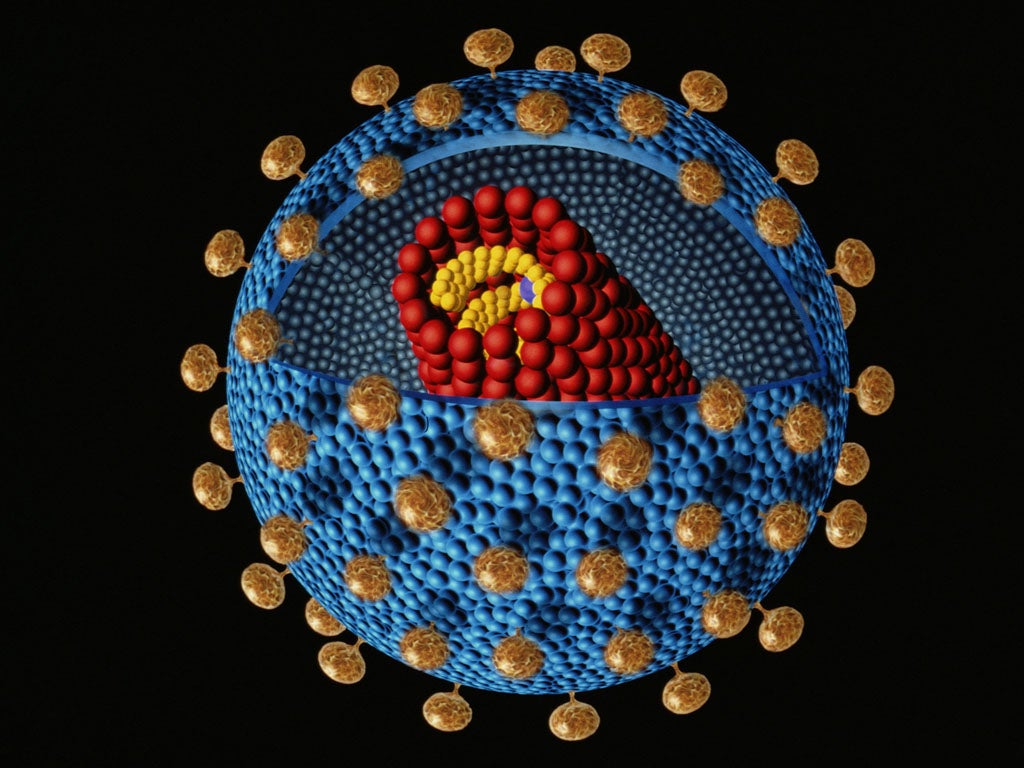

A vaccine designed to tackle SIV, the monkey equivalent of HIV, may have successfully cleared the virus from infected animals, paving the way for research into a HIV vaccine for humans.

It was previously thought that both the human and simian immunodeficiency viruses could be managed with antiretroviral therapies, but not eradicated.

However, a study published in the science journal Nature showed that of 16 monkeys exposed to the virus who were injected with a vaccine, nine appeared to be able to clear their body of the disease.

US researchers from the Vaccine and Gene Therapy Institute at Oregon Health and Science University are now hoping to use a similar approach to test for a vaccine equivalent in humans.

The team examined a strain of the virus called SIVmac239, which is up to 100 times more deadly than HIV.

Researchers first inoculated monkeys with the vaccine and then exposed them to SIV. The virus did not spread in over half of the inoculated monkeys, which usually die within two years of being infected.

The vaccine used a modified version of the cytomegalvirus (CMV), which belongs to the herpes family, to sweep through the monkey body and encourage the immune system to fight off SIV.

After being exposed to the virus, some monkey bodies began to respond by searching out and destroying signs of SIV. They remained clear up to three years after first being inoculated.

Prof. Louis Picker told the BBC: “It's always tough to claim eradication - there could always be a cell which we didn't analyse that has the virus in it. But for the most part, with very stringent criteria... there was no virus left in the body of these monkeys.”

However, he said the team were still trying to determine why the vaccine was only successful in nine monkeys.

“It could be the fact that SIV is so pathogenic that this is the best you are ever going to get", he explained.

“There is a battle going on, and half the time the vaccine wins and half the time it doesn't.”

Now, the team want to examine if the same technique could be developed and made safe enough to be successful in humans. Clinical human trials could start within two years if the vaccine is approved and the team receive permission from regulatory bodies, Prof Picker added.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks