Stargazing in January: a scintillating sparkling star in the south

Long known as the Dog Star, it’s the leading light of the constellation Canis Major, the Great Dog, which loyally follows the great hunter Orion across the night sky, writes Nigel Henbest

This winter, our skies are spangled with plenty of brilliant lights, headed up by the bright planets Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. But there’s one that stands out from the others: a scintillating light in the south that sparkles wildly in every colour you can imagine, like a diamond that’s out of control.

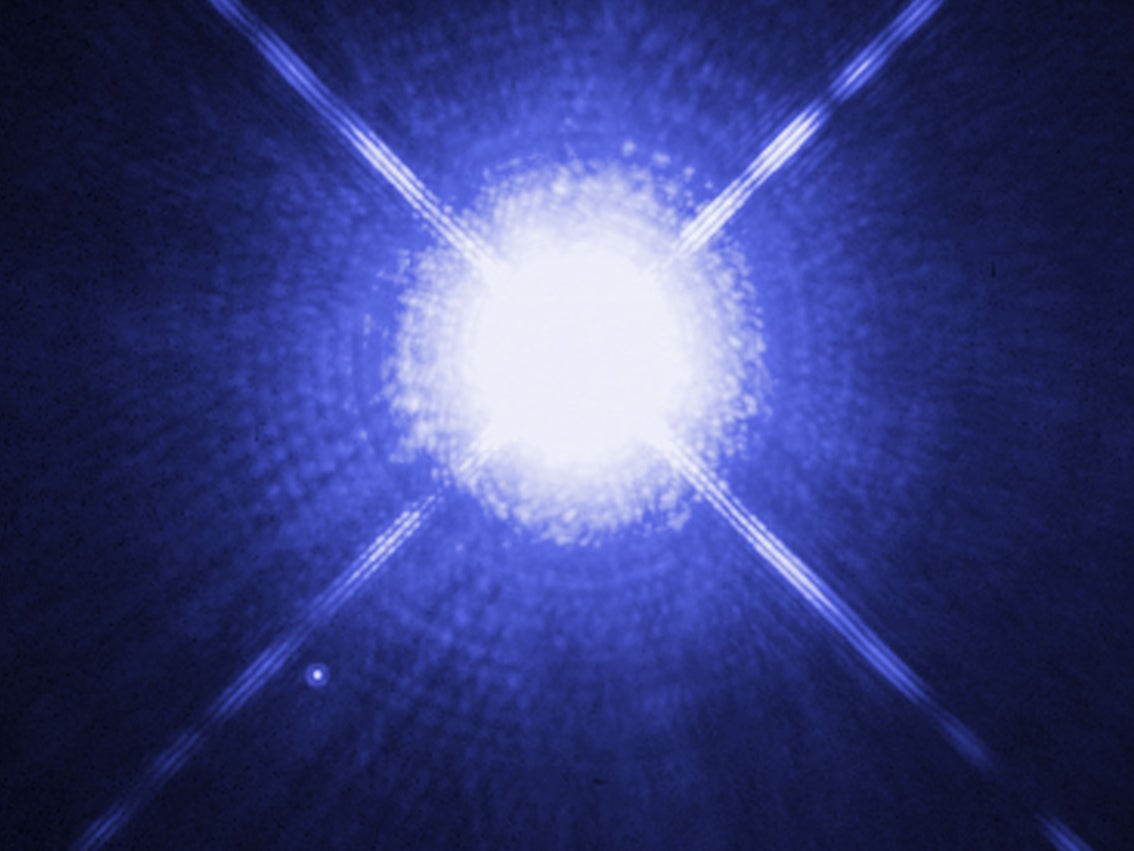

This is Sirius, the brightest star in the night sky. Long known as the Dog Star, it’s the leading light of the constellation Canis Major, the Great Dog, which loyally follows the great hunter Orion across the night sky.

If you view it from space, Sirius is a constant pure white beacon against the black of the Cosmos. But when we see it through the turbulent atmosphere above our heads, the light from Sirius is constantly bent and split into different colours by pockets of air at different temperatures and densities, acting as tiny fluctuating prisms. Each instant, the beam of light that reaches our eye can be a different colour of the rainbow, and the star appears to flash red, blue, green or white. All stars scintillate, but only Sirius is bright enough to trigger the colour receptors in our eyes.

Sirius has long fascinated people around the world. It was named Seirios (“scorcher”) by the ancient Greeks, who believed that the brilliant star added to the sun’s heat in summer, to create the hot humid “dog days”, when everything – including canines – slowed down. The ancient Chinese astronomers knew Sirius as “the celestial wolf”, and there are other canine associations in North America where various tribes saw this star as a sheepdog, a wolf or a coyote.

In ancient Mesopotamia, Sirius was the tip of an arrow that was being fired at Orion.

To the Polynesians, sailing the Pacific Ocean a thousand years ago, this star was the body of the giant sea bird Manu, its wingtips marked by Procyon and Canopus (below the horizon in our star chart). It guided their navigators to Fiji, where the star passes directly overhead.

Sirius was critically important to the Egyptian civilisation. Its appearance at dawn each August heralded the Nile floods, which covered the fields with fresh damp soil where they could sow their crops. In a land with little rainfall, it was natural to revere Sirius as the provider of their essential harvest.

Though Sirius is currently twice as brilliant as the next brightest star, Canopus, it wasn’t always this way. The Dog Star is a fairly run-of-the-mill specimen, and only appears so prominent in our skies because it’s passing nearby – on the cosmic scale – at a mere 8.6 light years. Prior to 90,000 years ago, Sirius appeared dimmer than Canopus; and it will eventually lose its title again when Vega swings past us.

Boasting a temperature of almost 10,000C, Sirius is twice as heavy as the sun. And it’s relatively young: just 230 million years old, as compared to the sun’s venerable 4,600 million years.

More interesting is its faint companion, which circles Sirius every 50 years. Nicknamed “the Pup”, it’s a white dwarf: a star that has puffed off its outer layers, to end up as a superdense object the same weight as the Sun, and yet only the size of the Earth. You’ll need a good telescope to spot this dim wee beast against the glare of Sirius itself, even though the Pup reaches its greatest separation from its blazing companion in 2023.

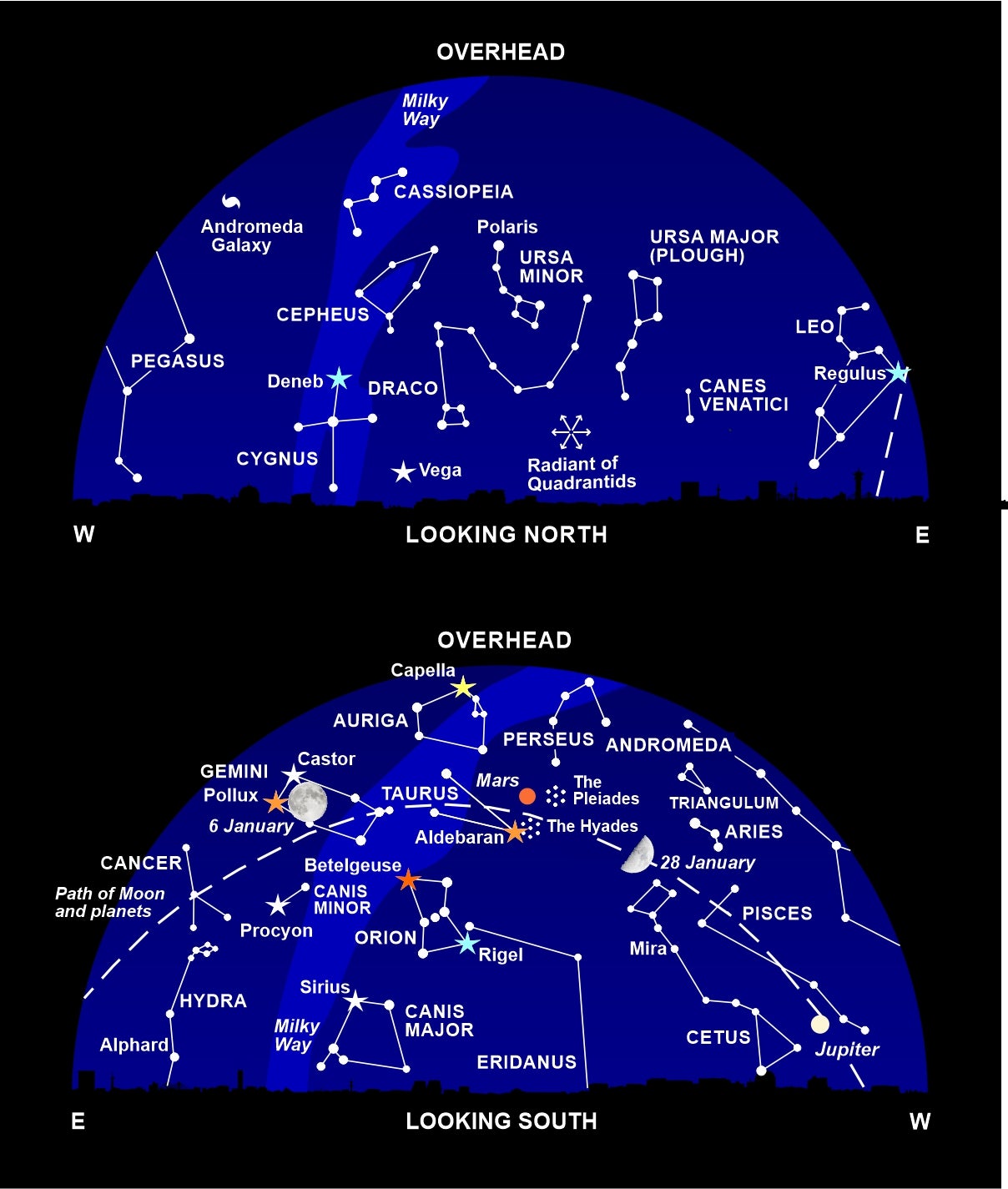

What’s up

You’ll find brilliant Venus low on the south-western horizon after sunset: the Evening Star will be with us for the next six months. At the beginning of the year, Saturn lies to its upper left; but Venus is rising inexorably in the sky, and it passes just below Saturn on 22 January when their separation is less than the diameter of the moon in the sky. The two planets are an unmatched pair, with Venus 75 times brighter than the ringed planet. The next evening (23 January) these two worlds form a lovely grouping with the thin crescent moon.

Higher up, giant Jupiter is dominating the late evening sky. The moon lies nearby on 25 January. Well to the left of Jupiter is Mars, now fading rapidly after its close approach to the Earth last month. The Red Planet lies in Taurus, near to the Seven Sisters (Pleiades) star cluster and the red giant star Aldebaran.

To the lower left of Mars is the familiar constellation of Orion, surrounded by a giant ring of stars that stretches from Aldebaran up to Capella, and then down through Castor, Pollux and Procyon to Sirius.

Diary

14 January: Moon near Spica

15 January, 2.10 am: Last Quarter Moon

21 January, 8.53 pm: New Moon

22 January: Venus very near Saturn

23 January: Moon near Venus and Saturn

25 January: Moon near Jupiter

28 January, 3.19 pm: First Quarter Moon

29 January: Moon near the Pleiades

30 January: Mercury at greatest elongation west; Moon near Mars, the Pleiades and Aldebaran

Nigel Henbest’s latest book, Stargazing 2023 (Philip’s £6.99) is your monthly guide to everything that’s happening in the night sky this year.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks