Stargazing in July: Space probe set to reveal Pluto’s secrets

This month, the sky is lit up by two full Moons

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.“Save Pluto!” cried the T-shirts. The slogan “stop planetary discrimination” screamed out on bumper stickers all over the States. “Honk if Pluto is still a planet!”, they urged. Pluto has long been every child’s favourite planet. Discovered in 1930 by the American astronomer Clyde Tombaugh, this tiny world has gripped the imagination of all and sundry.

But then it became evident that Pluto was not alone. It is a member of a swarm of Kuiper Belt Objects: minuscule worlds at the edge of our Solar System. And in 2005, a team led by Mike Brown – observing from Palomar Mountain – discovered a distant object even more massive (and possibly slightly larger) than Pluto.

The new body was named Eris – a Greek goddess of discord and strife. Her name is appropriate, because her discovery challenged the status of Pluto. In August 2006, at a meeting of the International Astronomical Union in Prague, Pluto’s ranking on the Solar System was downgraded to that of “dwarf planet” – much to the disappointment of Pluto aficionados. Now there are officially only eight planets in the Solar System.

But fans of the mini-world have an event to look forward to. On 14 July, the space probe New Horizons will arrive at the Pluto system after a nine-year journey through space. It will pass within 10,000km of the now-renamed dwarf planet and 27,000km from Pluto’s major moon, Charon. New Horizons will study in intimate detail the geology and chemistry of Pluto and its moons – the tiny world has at least five in total.

Alan Stern is the principal investigator on the New Horizons mission. And he is passionate about Pluto. He told us that the minuscule world is far more than a mere afterthought of the Solar System. “Pluto, Eris and their companions are part of a huge unexplored region of our planetary neighbourhood,” he explains.

What expectations does Stern have of the mission? “There’s the possibility of rings circling Pluto; ice-volcanoes like those found by astronomers on Neptune’s moon Triton; and maybe unexpected interactions between Pluto and Charon. I don’t make predictions’, he adds. “It’s all about exploration.”

After the Pluto fly-by, New Horizons will explore an uncharted zone of our Solar System: the frozen wasteland of the Kuiper Belt Objects – a twilight region where no spacecraft has ever been before. The lure of more exotic and distant worlds is drawing astronomers and space planners ever outwards.

What's Up

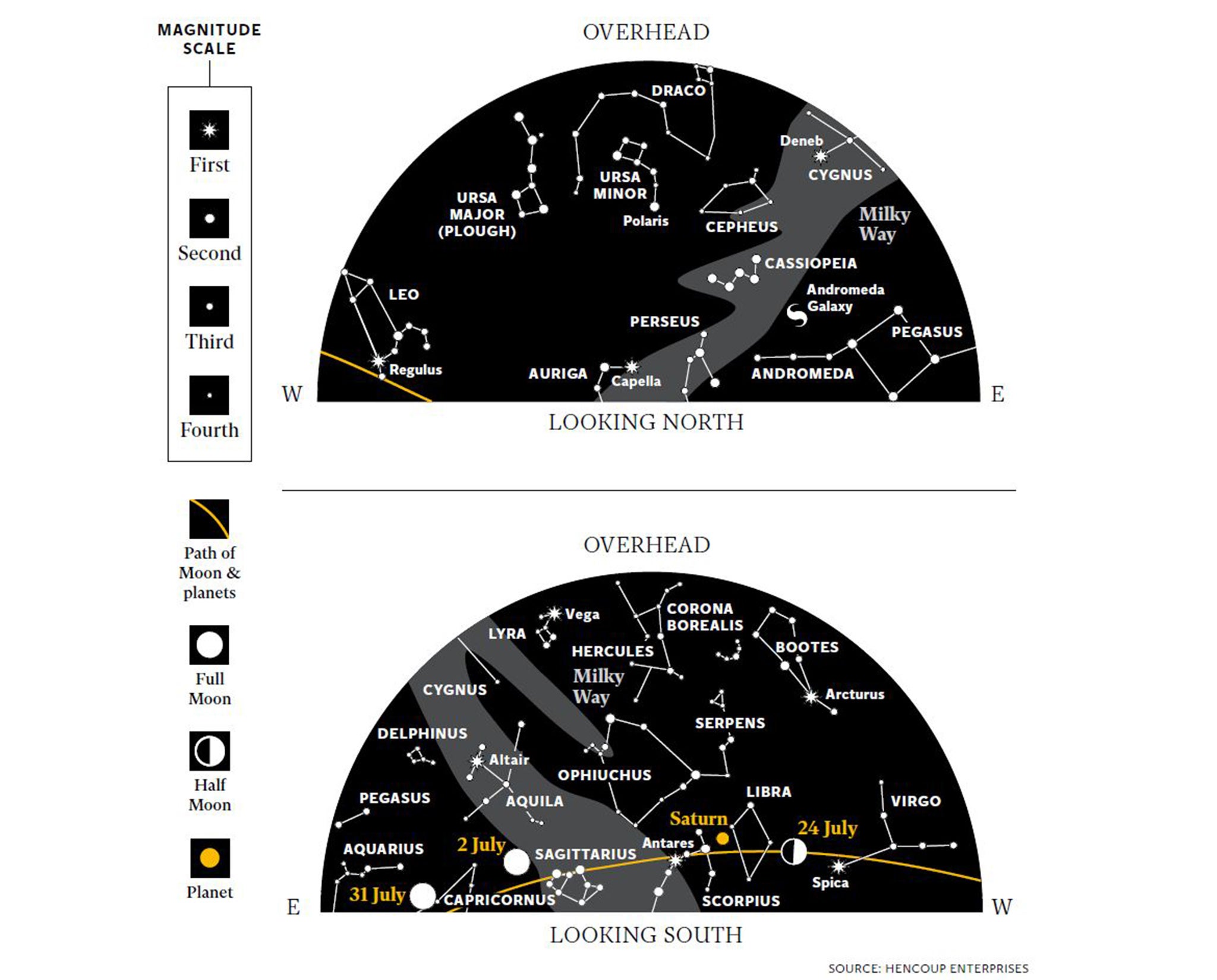

This month, the sky is lit up by two full Moons. It’s not an uncommon occurrence, and doesn’t mean anything – but expect a rash of publicity for the second full Moon on 31 July, which self-proclaimed pundits mistakenly call a blue Moon. Coming back to the very start of July, brilliant Venus is up close and personal with giant planet Jupiter, low in the north-west after sunset: on 1 July they are separated by less than the width of the Moon. But they’re sinking into the twilight glow, and by the end of July both Venus and Jupiter have disappeared from sight.

Later in the evening, Saturn is the sole planet you’ll spot, low in the south. The star to its left is Antares, marking the heart of Scorpius, the cosmic scorpion. The fearsome beast’s claws once encompassed the region where Saturn lies; but Julius Caesar chopped them off to form the constellation of Libra (the scales).

To the left of Scorpius you’ll find Sagittarius. In myth, he was an archer with the body of a horse and a human torso – but the principal stars irresistibly remind us of a teapot, complete with a puff of steam (a star cloud) rising from the spout! The centre of our Milky Way galaxy lies in this direction, but we get a poor view of the region from Britain, as Scorpius and Sagittarius are always low on the horizon. If you’re travelling south on holiday, though, you’ll have a grandstand view.

Even with the naked eye (away from bright lights), you’ll see star clusters and glowing nebulae dotted along the glowing band of the Milky Way. Pack a pair of binoculars, and you’ll be treated to a stunning panoply of celestial treasures.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments