Stargazing for December 2017: Sister lovers

It’s the perfect time of year to see the Pleiades in their full glory – and catch the Geminid meteor shower

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

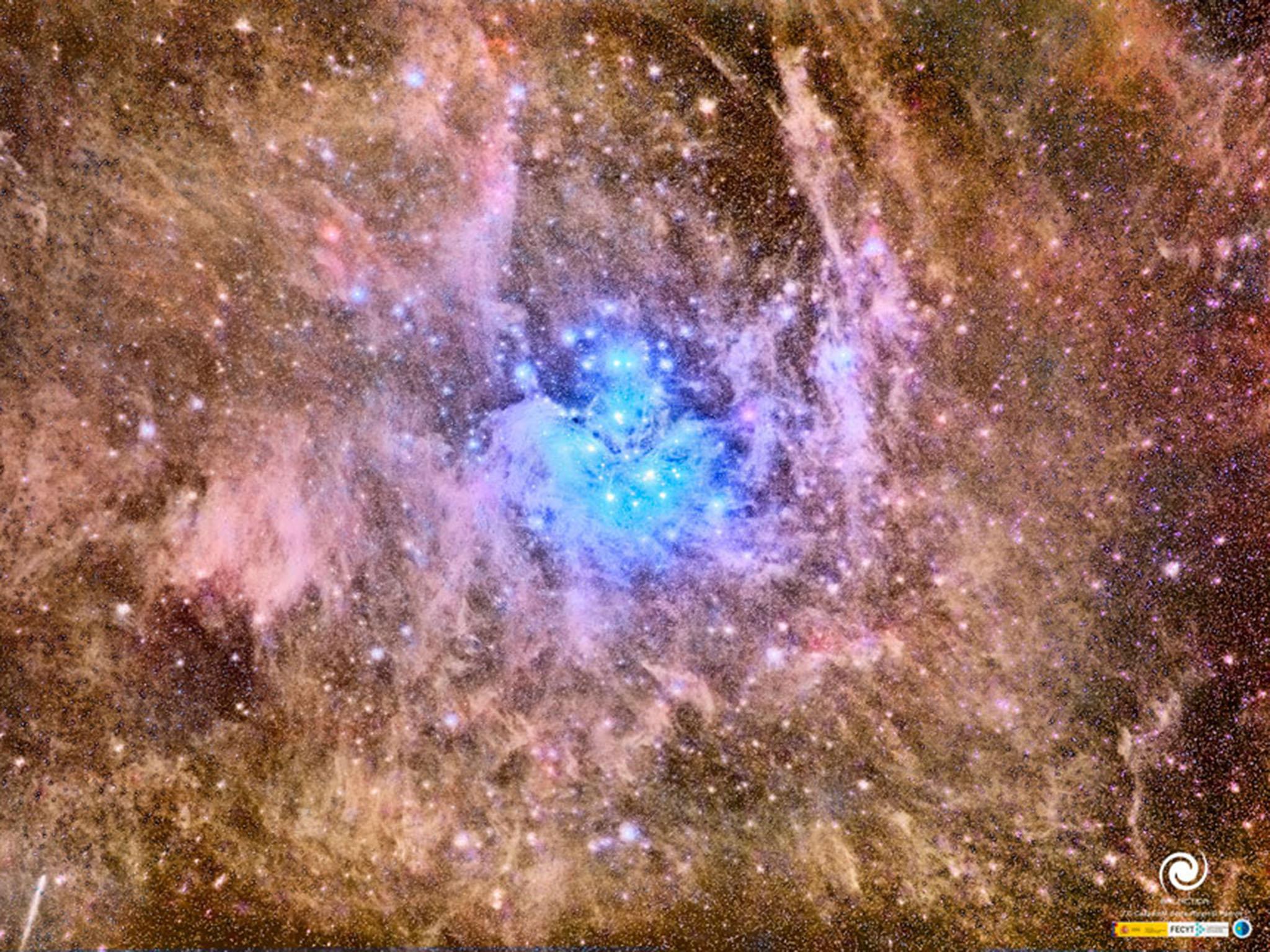

Your support makes all the difference.“Many a night I saw the Pleiads, rising thro’ the mellow shade/ Glitter like a swarm of fireflies, tangled in a silver braid” wrote Alfred, Lord Tennyson, in his poem “Locksley Hall”. There can never have been a more hauntingly beautiful description of the glorious Pleiades star cluster than this.

The Pleiades (Seven Sisters), are at their best this month, riding high in the southern sky. And it seems that other cultures have also appreciated the loveliness of this tiny group of stars.

They were named ‘plein’ by the Greeks, after their word ‘to sail’; presumably as a warning to mariners not to voyage across the Mediterranean in the dangerous winter months when the Pleiades were in the sky. The first artistic depiction that we have of them is on the Nebra Sky Disc from Germany, dating back to 1600 BC.

The Chinese recorded the Pleiades as early as 2357 BC; and the Polynesians used the diminutive cluster to help them navigate as they travelled thousands of kilometres across the Pacific. To them, these stars were the eyes of Rigi, a worm god who tried to raise the heavens, but broke up under the strain.

The Seven Sisters are one of the very few sky-sights to be mentioned in the Bible. God asks Job: ”canst thou bind the sweet influences of Pleiades?”.

The Mayan and Aztec people of Central America had a particular affection for the cluster, timing their most gruesome human sacrifices to coincide with the appearance of the stars.

Common to many cultures is the notion that the group is a family of female sisters, being pursued by an aggressive male – in this case, the constellation of Orion or the bright star Aldebaran, in Taurus. In fact, the Pleiades (and adjacent star cluster the Hyades) are also part of the constellation of the Bull.

Although they’re known as the Seven Sisters, most people see anything but seven! Most can spot six; those with better vision (and clear skies) can pick out nine or ten; while the keen-eyed Victorian astronomer William Rutter Dawes counted an astonishing thirteen.

Counting in all the faint stars only visible in a telescope, in reality there are about a thousand stars in the cluster. They’re a recent arrival on the cosmic scene: the brilliant blue-white stars are 75-100 million years old (as compared to our middle-aged Sun, which boasts an age of 4.6 billion years).

The cluster lies 440 light years away, and is surrounded by reflective dust. Many young star clusters are cloaked in the remnants of the natal gas-and-dust cloud that created them; but the Pleiades are too mature for that. Instead, they have encountered a passing cloud of gas in space, and their powerful radiation is destroying it.

Glorious as they are to the unaided eye, the Pleiades look sensational through binoculars, or a small telescope. But hurry: you only have 250 million years to see them as a cluster! That’s when it’s estimated that the Seven Sisters (and all their accompanying stars) will grow up, drift apart – and carve their own, independent lives around our Galaxy.

What’s up?

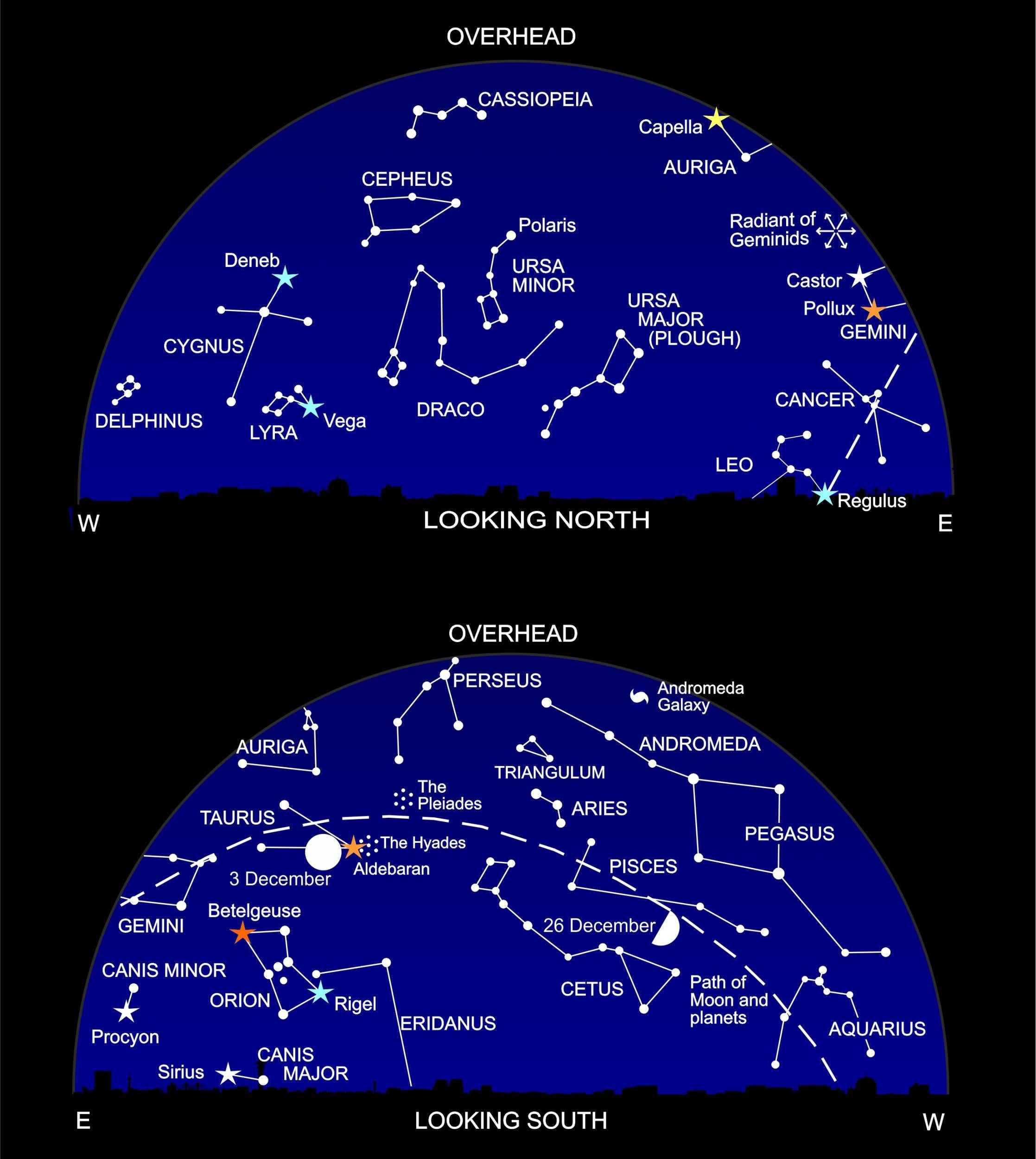

We’re in for a wonderful pre-Christmas display of celestial fireworks on the night of 13 December, when shooting stars from the Geminid meteor shower sparkle across the sky. This is the most prolific meteor show of the year, and in 2017 the Geminids promise to be better than ever, as the Moon is well out of the way and the sky will be gloriously dark.

Meteors are small specks of dust from space, burning up as they hit the atmosphere at over 100,000 km/hour. Usually, they are dandruff from hairy comets; but the Geminids are instead particles of grit spread by a rocky asteroid, called Phaethon. These solid particles incinerate themselves as bright shooting stars, often tinged yellow or blue.

Since they were first spotted in the nineteenth century, the Geminids have become more abundant every year, and we may spot a shooting star every minute or so. Because of perspective, the meteors seems to spread out from a point (the radiant) in the constellation Gemini. But they whizz across the whole sky, so you can spot them anywhere. Though there’ll be shooting stars all evening, they’ll reach a peak after midnight, as the Earth turns and the cosmic debris is impinging on us from almost overhead.

While the evening skies are now ablaze with the bright winter constellations – Orion the Hunter with his two dogs (Canis Major and Minor), the twin stars of Gemini and Taurus the Bull – you’ll have to wait till after midnight to spot any planets. Mars rises around 3.30am; followed by lordly Jupiter about 4.30am. And, at the start of December, you may catch brilliant Venus very low in the east before sunrise.

Meanwhile, the Moon is having a fun time this month. The Full Moon on 3 December is unusually near the Earth, making for an exceptionally large and bright ‘supermoon’ (though not as spectacular as the supermoon next month). As the Moon rises on 8 December, it’s lying right in front of the bright star Regulus: around 10.15pm you’ll see the star suddenly pop into view from behind the Moon’s dark edge. And on 30 December, the Moon lies in front of the Hyades star cluster in Taurus; around 1am, it hides – ‘occults’ in astronomers’ wonderful jargon – the bright red Aldebaran for about an hour.

Diary

8 December: Moon occults Regulus

10 December, 7.51am Moon at Last Quarter

13/14 December Maximum of Geminid meteor shower

18 December, 6.30am New Moon

21 December, 4.28pm: Winter Solstice

26 December, 9.20am Moon at First Quarter

30/31 December Moon occults the Hyades and Aldebaran

For the low-down on all that’s up in the sky next year, check out Heather Couper and Nigel Henbest’s latest book ‘Philip’s 2018 Stargazing Month-by-Month Guide to the Night Sky Britain & Ireland’

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments