Science news in brief: From mapping Antarctica to omnivorous sharks

And a roundup of other stories from around the world

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Mapping the South Pole

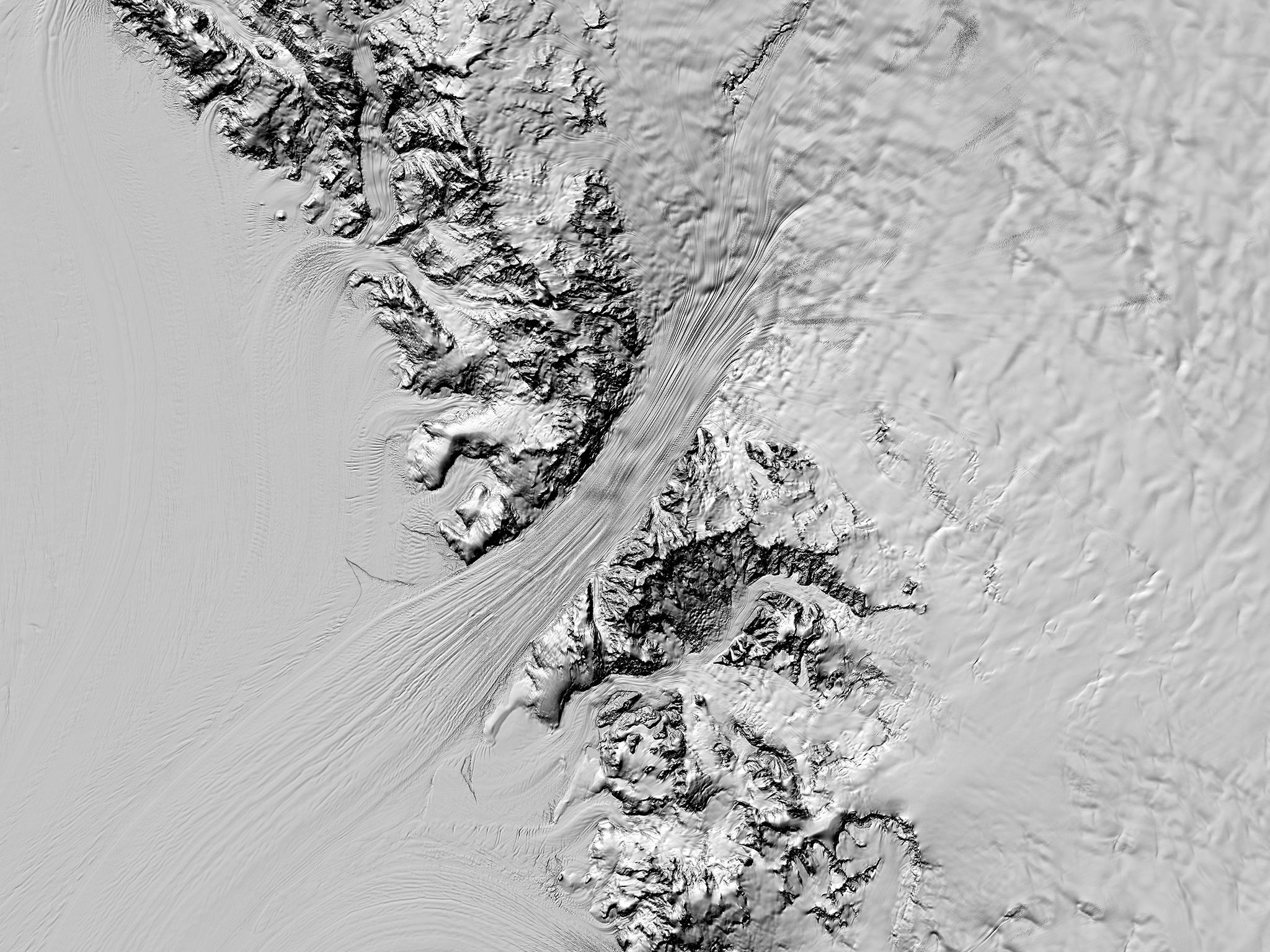

You may never make it to the South Pole, but you can now see Antarctica and its glaciers in unprecedented detail. Researchers recently announced the release of a new high-resolution terrain map, called the Reference Elevation Model of Antarctica or Rema, which they say makes Antarctica the best-mapped continent on Earth. Antarctica is the most desolate and inhospitable place in the world, and its remoteness makes monitoring changes in ice and water levels difficult. Because of the warming climate, seasonal changes at Antarctica are becoming more severe, making the need to understand the loss of ice even more important.

Ian Howat, the project’s principal investigator and a professor of earth sciences at Ohio State University, used data from a constellation of polar orbiting satellites to image the frozen wastes. “If you’re someone that needs glasses to see, it’s a bit like being almost blind and putting on glasses for the first time and seeing 20/20,” says Howat. The team used 187,585 images collected over six years to create the map. Observing snowfall, ice growth and the rate of melt and fissures will allow scientists to monitor sea-level rise and glacial melt with more accuracy. Explorers and scientists stationed at Antarctica will also find the map useful. By having such a detailed topographical map, new routes to science stations can be planned around the continent’s dangerous terrain.

Sting in the tail for parasitic wasps

Parasites have a leisurely lifestyle – they set up camp at someone else’s place, live off their food and therefore profit (evolutionarily speaking). But new research shows that sometimes the parasite gets a taste of its own medicine, and from an unexpected source. Scientists studying wasps that target oak leaves found that a second parasite, a vine, can get its tendrils into the homes set up by the wasps, called galls, subverting their diversion of the host’s resources. After that, things don’t go so well for the wasp. Galls are like in-law apartments for parasites: swollen masses of plant tissue that route nutrients to wasp larvae, which grow and develop safely within until they are mature enough to leave.

When researchers behind the paper, published recently in Current Biology, first encountered a gall with small woody suction cups dug into it, it looked so strange they wondered if it had been collected by mistake. But cutting open the growth revealed the body of a wasp inside, confirming its gall status. When the researchers dissected 51 love-vine-infested galls from one wasp species, they found 45 per cent contained a mummified adult wasp, compared with only 2 per cent of uninfested galls. That suggests that the love-vine interferes with the wasp’s nutrition so it develops fully but is not able to leave. And the host tissue within dissected galls was twisted towards the vine’s entry points, showing it was coopting the gall’s nutrients.

Omnivorous sharks that diet on sea salad

Sharks are not known for their taste for greenery. But at least one species of shark enjoys eating a salad of sea grass as well as the prey it hunts. The bonnethead shark, a diminutive species that reaches up to 3ft in length, lives in the shallow sea grass meadows off both coasts of the Americas. It eats small squid and crustaceans ferreted from the swaying underwater fronds. But researchers say in a study published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B they also eat large quantities of sea grass. The grass isn’t just passing inertly through the sharks’ guts. They extract nutrition from it just as they do from the meaty portion of their diet. These sharks must, therefore, be reclassified as omnivores – the first omnivorous sharks known to science.

Researchers caught bonnethead sharks just off the Florida Keys and transported them to an outdoor lab. There, the sharks lived in a large tank and received a meal every day of a wad of sea grass wrapped in a piece of squid, resembling a large inside-out sushi roll. The sea grass, which made up 90 per cent of the roll, had been loaded with a tracker isotope that could be detected later in their blood if the grass was truly being digested. The researchers also tested the sharks’ feces. The sharks thrived on this diet.

Hundreds of seals dying from measles-like illness

Harbor and grey seals are dying by the hundreds, from southern Maine to northern Massachusetts, apparently from a combination of a measles-like illness and flu. Late last month, the federal government declared the summer’s deathtoll on seals an “unusual mortality event”, meaning federal resources would be provided to help understand and cope with the deaths. Teams have responded to more than 600 reports of dead or dying harbor and grey seals, but there are probably more that have gone unreported or washed up on private property, says Mike Asaro, chief of the marine mammal and sea turtle branch of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). “The total could be up to 1,000 at this point. We just don’t know,” he says. The carcasses washing up on New England beaches reveal an epidemic that’s touching all ages, says Katie Pugliares-Bonner, a senior biologist and necropsy coordinator for the New England Aquarium in Boston.

Although research is still underway, the disease outbreak appears to be centred on the Isles of Shoals, a small group of islands off the coasts of southern Maine and northern New Hampshire, Pugliares-Bonner says. Animals are suffering from phocine distemper virus, which is closely related to canine distemper in dogs, and a cousin of the measles, says Tracey Goldstein, a professor at the University of California, Davis, and a member of NOAA’s unusual mortality working group. Phocine distemper causes lung infections and seizures as it attacks the seal’s brain tissue. Some of the seals have also been found to have flu. Infections are more likely to spread at this time of year, when the seals are living in close quarters as they nurture their babies on the beaches, she says.

A hummingbird in hand... how to feed them

It’s fun to feed hummingbirds and see them up close – almost like encountering fairies. But how? Start by picking out a spot and staying very still. And try wearing lots of colours. “A really gaudy Hawaiian print shirt is an excellent hummingbird attractor,” says Sheri Williamson, a naturalist, ornithologist and author of A Field Guide to Hummingbirds of North America. Your best chance to hand-feed hummingbirds is when they’re under stress, like this time of year, when some birds are preparing to migrate and unsure where they’ll find their next meal. Should people feed hummingbirds like this? “It’s sort of a meditative exercise we could all use to slow down a bit,” says Williamson. “Sitting still, you start to notice things in your garden you may not have noticed before. It makes for a nice excuse to get out and just commune with nature.” But getting hummingbirds too accustomed to people can make them vulnerable to those who may swat at them out of fear or attract them for reasons other than just observation. “There are reports of people attracting hummingbirds and doing terrible things to them,” she says, like selling them as love charms

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments